Who clothes there?

LEARNING ABOUT ANCIENT FASHION FROM NATURAL HISTORY COLLECTIONS

By Ella McKelvey, Web Content and Communications Officer

Tucked in a display case in the southwest corner of the Museum is a sculpture of an unidentified female figure, small enough to fit in your coat pocket. It is a replica of one of the most important examples of Palaeolithic artwork ever discovered; a 25,000-year-old carving known as the Venus of Willendorf. The Venus of Willendorf is one of several Palaeolithic statues found in Europe or Asia believed to depict female deities or fertility icons. Known collectively as the Venus Figurines, the carvings are similar in size and subject matter, but each has her own peculiarities. Many are naked, but some of the later examples are wearing distinctive garments, clothes we might describe today as ‘snoods’ or ‘bandeaux’. The Venus of Willendorf is easily distinguished by her statement headpiece; perhaps a spiralling hair-braid or ceremonial wig. But there is another, more exciting interpretation — this strange, thimble-like adornment might actually represent a woven fibre cap, making it the oldest ever depiction of human clothing.

The Venus Figurines are incredibly important to the study of human fashion because they significantly predate any direct archaeological evidence of ancient clothing. The oldest surviving garment dates back an astonishing 5,000 years; an exceptionally-preserved linen shirt discovered in an Egyptian tomb. But our species, Homo sapiens, has a much longer history, perhaps up to a quarter of a million years. How much of this time have we spent wearing clothing? And why did we even begin to dress ourselves in the first place?

By comparing human genes to those of our furrier primate relatives, researchers have been able to estimate that modern humans lost their body hair around 240,000 years ago. A mutation in a gene called KRTHAP1 likely led to a decrease in our production of the protein keratin, the building block of hair. The exact reason why this mutation spread through the population is still up for speculation. One commonly held theory is that, with less body hair, our ancestors could sweat and tolerate higher temperatures, allowing them to expand their habitats from sheltered forests into sun-drenched savannahs. But at some stage, our ancestors started covering their skin again — leaving us to wonder when nakedness became a nuisance.

An intriguing clue about the circumstances that led to the adoption of clothing has come from studying the DNA of our parasites — namely, clothing lice. In 2010, researchers used genetic sequencing to determine that clothing lice split from their ancestral group, head lice, between 170,000 and 83,000 years ago. When compared with genetic data from our own species, we can begin to weave a story about the origins of clothing that ties in with human migration. Gene sequencing has helped us work out that Homo sapiens originated in Africa but must have begun migrating towards Europe between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago, a window which overlaps neatly with the evolution of clothing lice. Is it possible that clothing lice are a consequence of the widespread adoption of clothing; a result of humans migrating into more northerly latitudes with cooler temperatures?

Curiously, there are indications in the archaeological record that human clothing could date to an even earlier stage in our species’ history than the expansion of humans into Europe. In 2021, researchers uncovered 120,000-year-old bones from a cave in Morocco believed to be used to process animal hides. There is a strong possibility that humans would have used these tools to make wearable items out of hunted animals, including blankets, cloaks, or perhaps more structured garments.

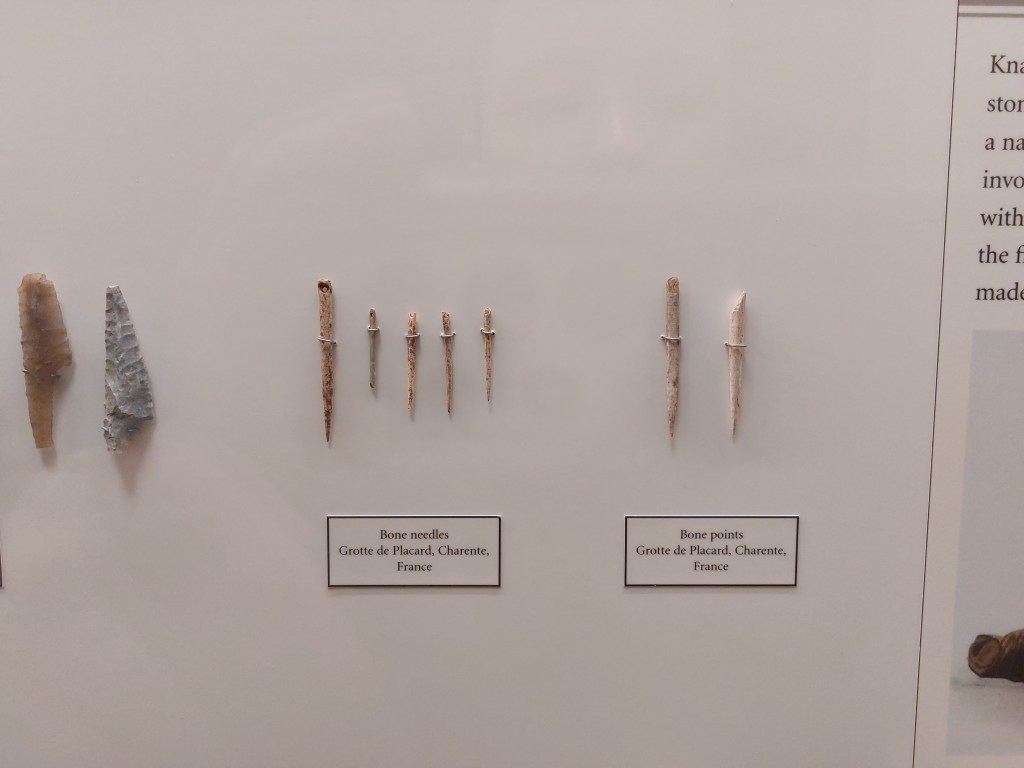

It seems likely that the first clothes humans made from hides were loose-fitting capes or shawls, which may have been more important for protection or camouflage than keeping warm. There are numerous reasons why other animals cover themselves with foreign objects besides thermoregulation. ‘Decorating’ behaviours occur in animals as diverse as crabs, birds, and insects, allowing them to disguise themselves from predators, or protect themselves from UV radiation. While early humans might have only needed simple clothing items to aid with disguise, as the climate began cooling 110,000 years ago, cloaks probably wouldn’t have cut it; our species must have learned how to make multi-layered and closer-fitting garments to maintain high enough body temperatures. Archaeology provides a similar estimate for the adoption of constructed garments, based on the discovery of 75,000-year-old stone awls — tools used for puncturing holes in hides to prepare them to be sewn together.

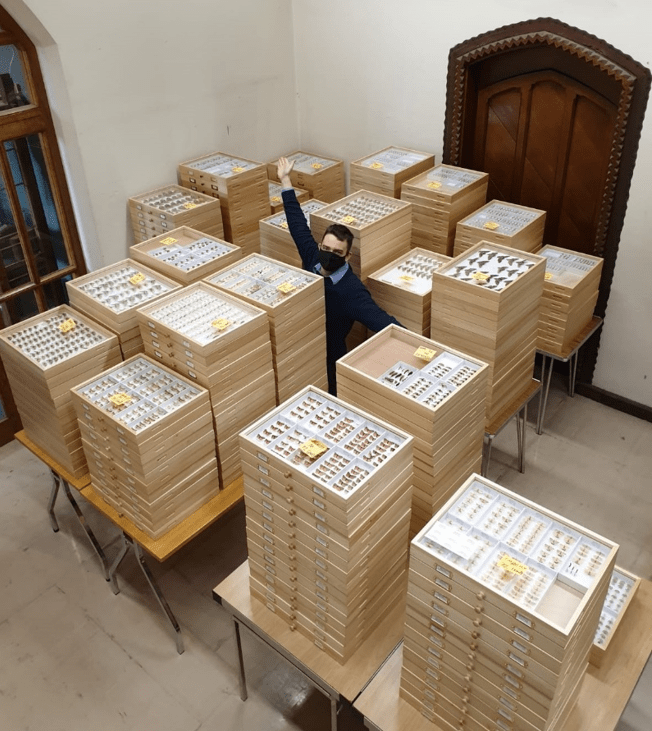

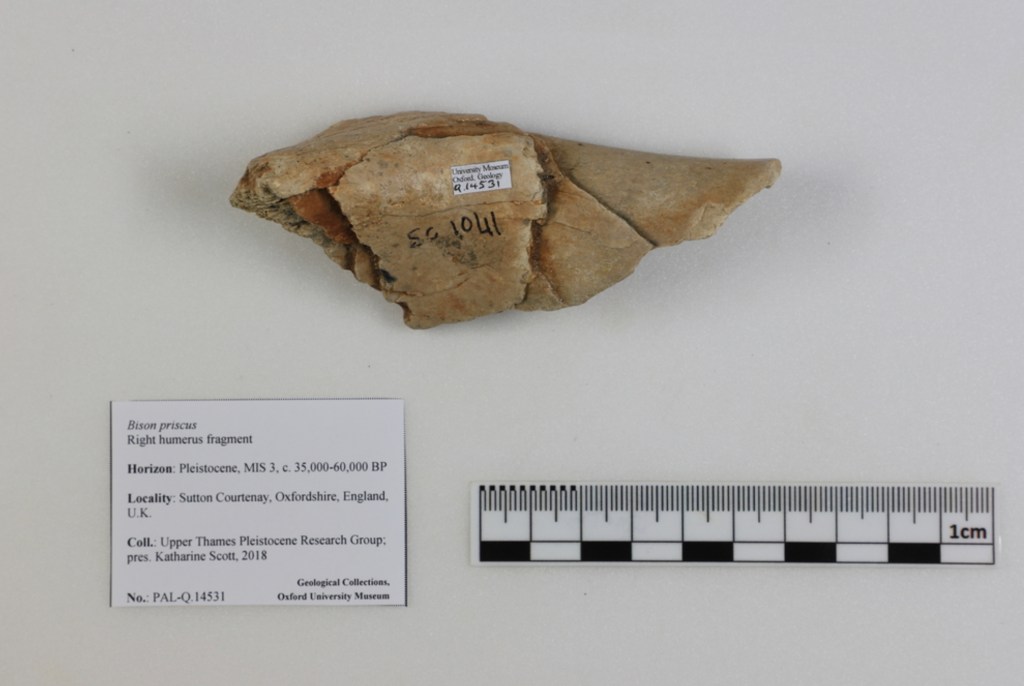

Homo sapiens‘ ability to make complex clothing items may have helped give our ancestors a competitive edge over the Neanderthals in Europe. Researchers have studied sub-fossil material in museum collections to learn about the changing distributions of European mammals throughout human history, allowing them to deduce that Neanderthals only had access to large animals like bison to make cape-like clothing from. But, in addition to bison, Homo sapiens lived alongside other, fluffier animals like wolverines during the last Ice Age, which could have been hunted to make warm trims for our clothing. Studies like these are highly speculative, but with such a threadbare archaeological record, they contribute valuable insight into the landscapes of ancient Europe.

The Neanderthals might have been less well-dressed than our Homo sapiens ancestors, but we can’t be certain that humans of our own species were the only prehistoric fashionistas. The oldest sewing needle to have ever been discovered dates to 50,000 years before present and was actually found in a cave associated with Denisovans — a group of extinct hominins we know little about. The Denisovans may be an extinct subspecies of Homo sapiens, but they might also have formed an entirely separate species altogether, perhaps learning how to sew independently of modern humans.

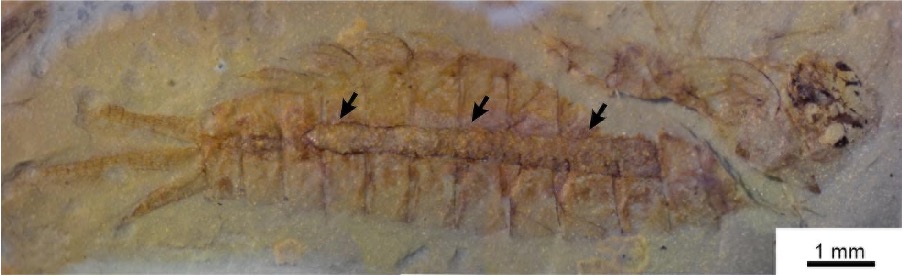

Following the invention of sewing was another crucial innovation in the history of human clothing — the ability to make textiles. In 2009, a group of researchers discovered 36,000-year-old evidence of textile-based clothing in the form of microscopic flax plant fibres that had been dyed and twisted together. There are many potential uses of twisted fibres such as these, but scientists have been able to study the organisms associated with the fibres, finding the remains of skin beetles, moth larvae, and fungal spores that are all commonly associated with modern clothing. Humans do not simply fashion clothes, we also fashion microhabitats, capable of supporting organisms as diverse as insects, fungi, and bacteria.

The discovery that humans have been making textiles into clothing for 36,000 years lends credence to the theory that the Venus of Willendorf is wearing a woven cap — but we might never be able to draw any certain conclusions about such an ancient artefact. Until just ninety years ago, humans could only make textiles from biodegradable materials, meaning that we have very little evidence about the clothing that our ancient ancestors wore. Thankfully, however, the story of human fashion is closely interwoven with the natural histories of hundreds of other species, allowing us to stitch together a patchwork history, utilising evidence from all corners of the kingdom of life.