Open Doors

OXFORD UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AT THE INTERFACE OF ‘TOWN’ AND ‘GOWN’

By Rawz, Sound Artist in Residence for 2022, St John’s College, Oxford

Oxford is a curious place and, for me, it’s getting curiouser and curiouser.

I love this city; I’ve called it my home for more than three decades. I couldn’t picture myself living anywhere else. But recently, I realised I’d only ever really seen half of my fair city, that there was a world beneath the dreaming spires that I had never even considered that I would be permitted to explore. I realised that I had never really walked through Oxford city centre; I had always been guided around it by 10 foot high fortifications and locked doors.

I grew up very much on the town side of Oxford’s notorious ‘town versus gown’ divide. I left school with no qualifications, and since then have spent much of my working life supporting the most marginalised people in the city, particularly young people struggling with formal education as I did. Doing this in a city whose very name is a buzzword for elitism and privilege means that I’m no stranger to juxtaposition. It continues to influence my art to this day.

I’m a hip hop artist, primarily focused on lyric writing and poetry. In 2009 I set up my own business, the Urban Music Foundation, with the hope that I could pass on some of the art skills that helped me get through tough times growing up, and that have enabled me to express myself fluently as an adult, and build a career around my art. I’ve found music and lyrics to be a uniquely useful tool in communicating ideas that are hard to transmit in any other way. Someone once said to me that music is what emotions sound like, and I’ve found that to be true.

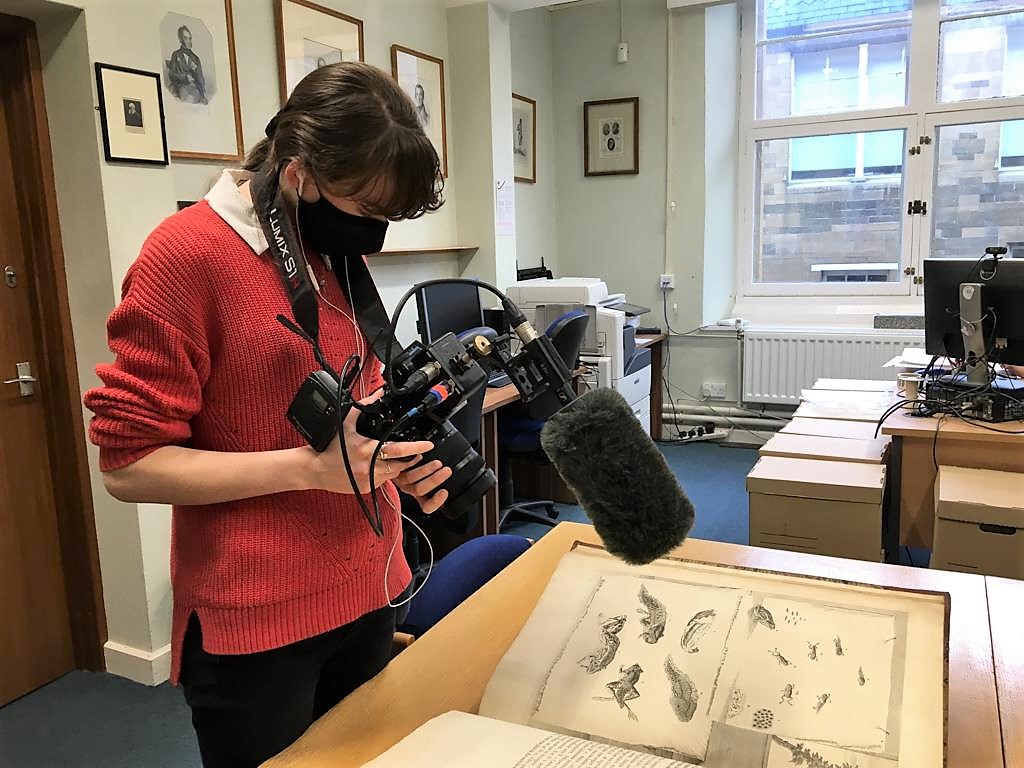

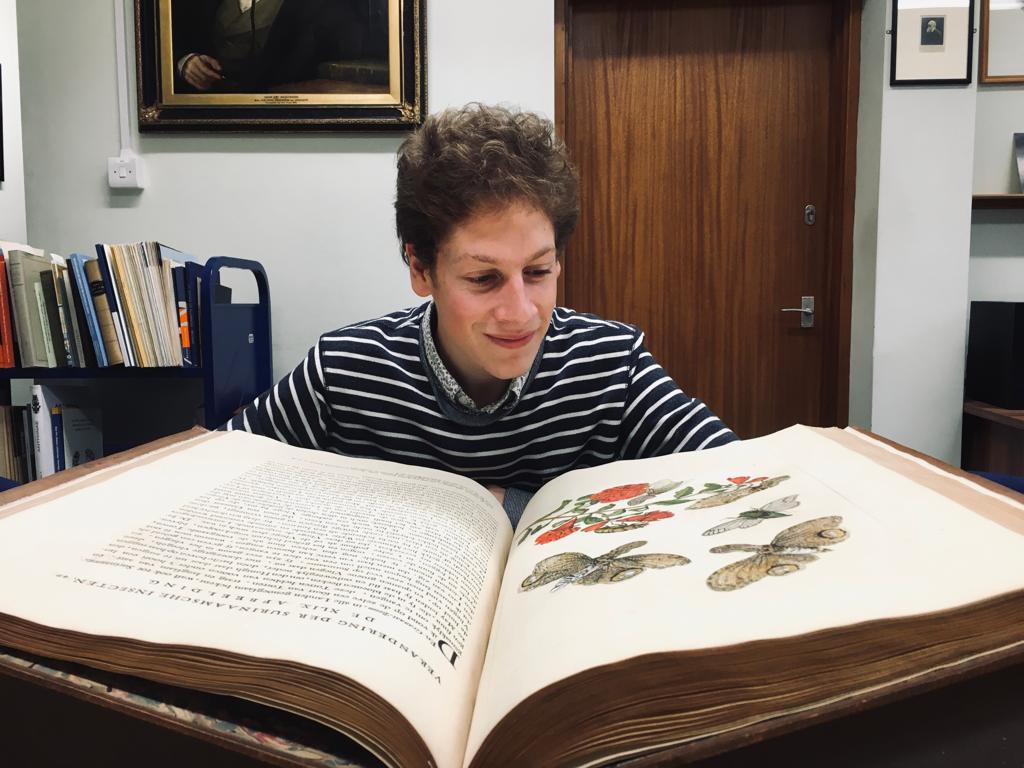

After a video call with one of GLAM’s community engagement team during the lockdowns of 2020, I had an idea for a project that became Digging Crates — a decolonisation project using hip hop music to reinterpret the musical instrument collection at the Pitt Rivers Museum, next door to the Museum of Natural History. I immediately saw the project’s value as a way to analyse and address some of the divisions and imbalances I see in Oxford, and in wider society. Just over a year after I sat down and wrote the original proposal for this project, I was offered the position of Resident Sound Artist for 2022 at St John’s College. Even as I write this I feel a surreal mix of pride and disbelief — not many people from my community in Blackbird Leys would have considered the idea of being offered such a post in their wildest dreams!

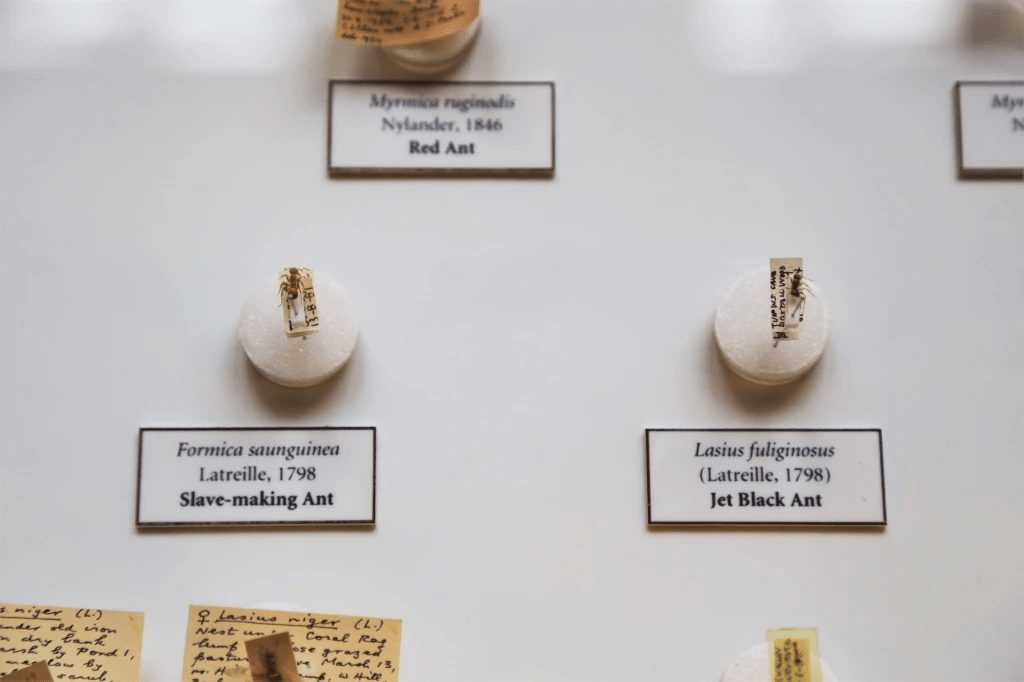

The past 18 months have seen doors open – both literally and figuratively – that I had never even considered walking through. I hope they continue to do so, and that they remain at least a little ajar for those following my path. Many of you, dear readers, will be glad to know that one place I have enjoyed exploring, both as a “townie” and, more recently, in my newer self-proclaimed title as “Town Ambassador to the Land of Gown”, is the Museum of Natural History. Of all Oxford’s museums, the Museum of Natural History has the biggest impact as soon as you walk through the doors (which are usually wide open). I’ve taken many “disengaged” and “hard to reach” young people to visit, and the heady cocktail of stuffed animals, dino bones, and cool rocks almost always proves irresistible to all but the most sceptical children, young and old. I would love an opportunity to get creative in this amazing space and am often trying to think of an excuse. Any ideas – you know where to find me!

Whatever happens next, stepping through the looking glass into this strange new world of the gown with its quirky, bizarre traditions, and its fascinating, inspiring, and problematic histories, is an experience I will never forget. I’m honoured to be the person taking this step on behalf of my community, and grateful for all those who worked hard and made sacrifices for me to be able to do so.

Want to find out more?

This link will connect you to some of the projects I am working on and some of my past works: https://linktr.ee/rawz_official I’d love to connect with you on social media or via any other means, I’m always up for discussing this important work.

If you’d like to attend my next workshop at St John’s on March 10th, we will be watching the documentary made during Digging Crates and I’ll be sharing some behind the scenes photos and stories, you can sign up via this link: https://www.sjc.ox.ac.uk/discover/events/workshop-digging-crates-project-and-film-screening/