Priceless and Primordial

Cataloguing the Brasier Collection

In 2021, the Museum was grateful to host PhD students Sarah Skeels and Euan Furness on research internships. Together, Sarah and Euan made a significant contribution to the cataloguing of the Brasier Collection — a remarkable assembly of fossils and rocks donated to the Museum by the late Professor Martin Brasier. Here, Sarah and Euan recount their experiences inventorying this priceless collection of early lifeforms.

Sarah Skeels is a DPhil Student in the Department of Zoology, University of Oxford

My short internship at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History came at a transitional point in my research career, starting a few days after submitting my PhD thesis. By training, I am a Zoologist, and my PhD thesis is on the electrosensing abilities of weakly electric fish. However, I have had an interest in Palaeontology for a long time, having studied Geology as part of my undergraduate degree. As such, the internship provided me with a unique opportunity to reflect on a subject I had studied many years before, whilst also developing new academic research skills.

The goal of my internship was to improve the inventory of the microfossils held in The Brasier Collection and to photograph some of these specimens, all in the hopes of increasing the utility of the collection to students, researchers, and hobbyists alike.

The Brasier Collection is rich in microfossils — small fossils that can only properly be inspected with either a light or electron microscope. Those stored in the Collection represent the fragmentary remains of a diverse array of animal groups that lived in the Cambrian, an important period in the Earth’s history when animal life diversified hugely, giving rise to many of the modern phyla that we know and love. The microfossils I examined came from a number of localities across the globe, including Maidiping in China and Valiabad in Iran. The specimens are exquisite in detail, which makes it difficult to believe that they are hundreds of millions of years old.

These fossils are of huge importance, helping us to understand the emergence of early animal life, and its evolution into all of the wonderful forms that exist today. The fossils are also useful because they can serve as markers of the age of different rock forms. By helping to improve the way these specimens are catalogued, I like to think that I am contributing to the preservation of Professor Brasier’s legacy. The whole experience was incredibly rewarding, and I can’t wait to see what new discoveries are made by those who study this unique set of fossils.

Euan Furness is a PhD student at Imperial College London

Oxford University Museum of Natural History has a range of objects on display to the public, but a lot of the curatorial work of the Museum goes on behind the scenes, conserving and managing objects that never come into public view. Collection specimens often don’t look like much, but they can be the most valuable objects to researchers within and outside the Museum. While there are a few visually striking pieces in the Brasier Collection, the humble appearance of most of the Brasier specimens belies their importance.

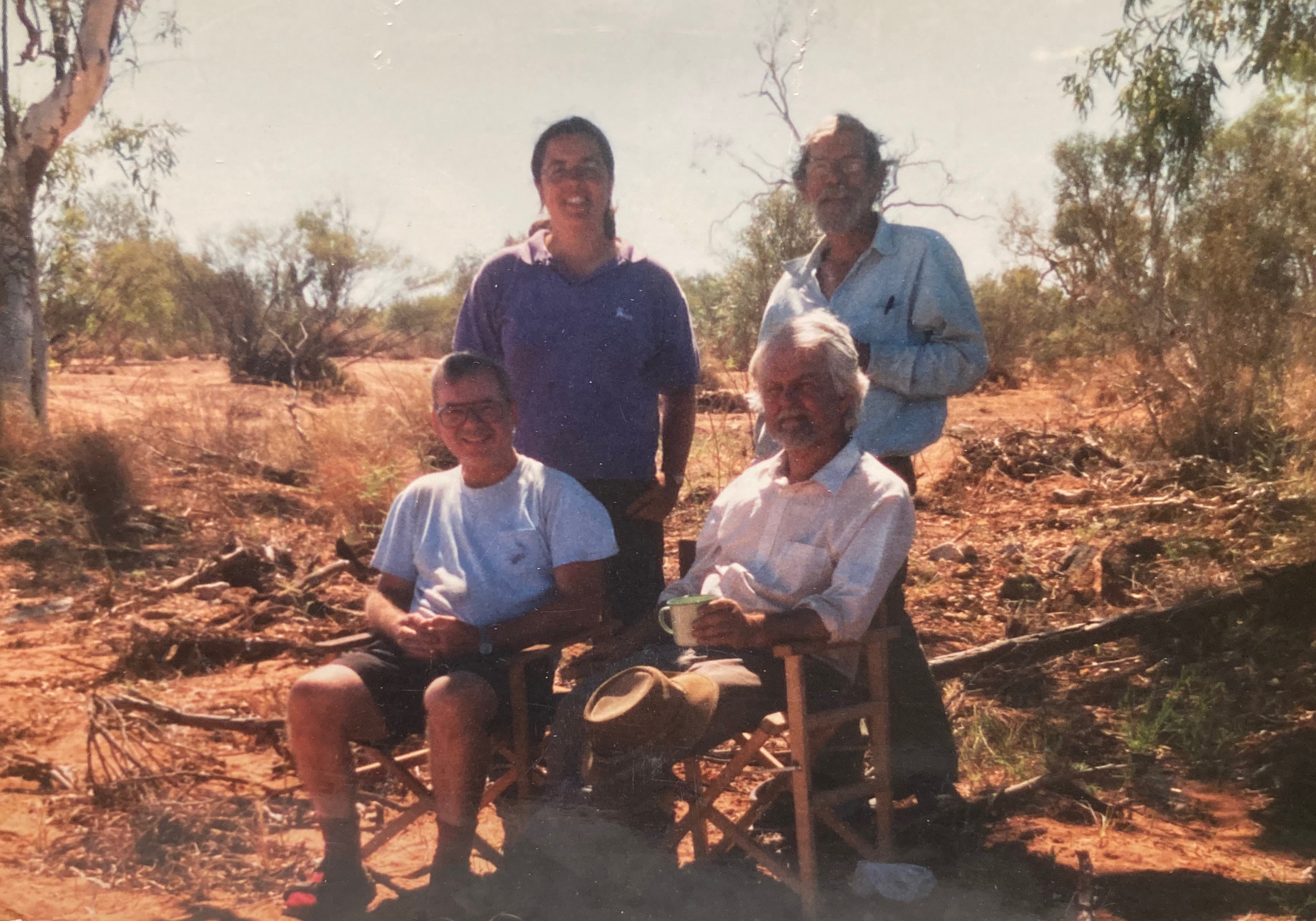

Left: A photo of Professor Brasier (bottom right) and friends, found in the Collection. Middle: Euan cataloguing in the Hooke basement. Right: An unusually well-preserved archaeocyathid (extinct sponge) from the Cambrian of Australia. Photo by Euan Furness.

The Brasier Collection came to the Museum in bits and pieces from the Oxford University Department of Earth Sciences, with the last of the specimens arriving in September 2021. The Museum therefore needed to determine exactly what they had received before they could decide how to make the best use of it. This meant searching through boxes and drawers behind the scenes and pulling together as much information as possible about the new objects: dates and locations of collection, identity, geological context, and the like. Only then could the more interesting specimens be integrated with the existing collections in the drawers of the Museum’s Palaeozoic Room.

Owing to Professor Brasier’s research interests, the addition of the Brasier Collection to the Museum’s catalogue more than doubled the volume of Precambrian material in its drawers. With that in mind, it was finally time for the Precambrian to be given a set of cabinets to call its own. This seems only fair, given that the Precambrian was not only a fascinating period in the Earth’s history but also the longest!

Having sorted through the new Brasier Collection at length, I think it’s not unreasonable to hope that the unique array of objects it adds to the Museum’s collections will facilitate a great deal of research in the future. For that, we must thank Martin for his generosity.