Imagine a drop of ancient resin. Inside is an insect, trapped for 53 million years, so well preserved it looks like it might twitch back into life. These amber fossils offer us a breathtaking glimpse into long vanished ecosystems. But there’s a catch: the most revealing details, like delicate mouthparts or microscopic genitalia, are sealed away under the resin’s glossy surface. Cutting into them would destroy what makes them precious.

Enter the SOLEIL synchrotron.

At SOLEIL, near Paris, a group of researchers led by OUMNH’s own Dr Corentin Jouault are preparing to shine one of the world’s brightest X-ray beams through over 100 blocks of Oise amber, each containing a fossilised insect no larger than a fingernail. The goal is to see inside without cracking them open. Using a technique called in-line phase-contrast synchrotron microtomography (a bit of a mouthful, so let’s call it “supercharged 3D X-rays”), the team hopes to reveal anatomy invisible to conventional CT scanners. Think of it as upgrading from grainy black-and-white TV to ultra-high-definition.

The impressive imaging setup of the ANATOMIX beamline at SOLEIL Synchrotron. In the foreground, a rotating platform holds the amber sample in the path of the X-ray beam, turning it a full 360° so that hundreds of 2D X-ray images can be captured from every angle. In the background are the scintillators, which transform invisible X-rays into visible light, and above them, the high-resolution camera that records these images. All the data are then processed by powerful computers to reconstruct a detailed 3D model of the fossil trapped in amber.

Dr Corentin Jouault carefully positioning a piece of Eocene Oise amber (approximately 53 million years old, from France), containing an undescribed extinct ant species, mounted on a scanning electron microscope stub, in front of the X-ray beam for a high-resolution scan (pixel size ≈ 1.3 μm).

Why does this matter? Well, these insects lived during the Early Eocene, around 53 million years ago, when flowering plants had taken over the world in what scientists call the Angiosperm Terrestrial Revolution (ATR). This upheaval transformed landscapes and diets alike, and insects, already an evolutionary success story, had to adapt. Some lineages thrived by exploiting new blooms, while others dwindled. By studying the fine details of insect mouthparts, researchers can track how feeding strategies shifted in tandem with the rise of flowers.

The plan is ambitious. Each piece of amber will be scanned in full at a resolution fine enough to spot features a few micrometres across (a micrometre is one-thousandth of a millimetre — about one-hundredth the width of a human hair). 20 chosen specimens will then be magnified further still for an even sharper look, down to less than half a micrometre per pixel. In other words, one pixel will cover an area 140 times smaller than the thickness of a human hair.

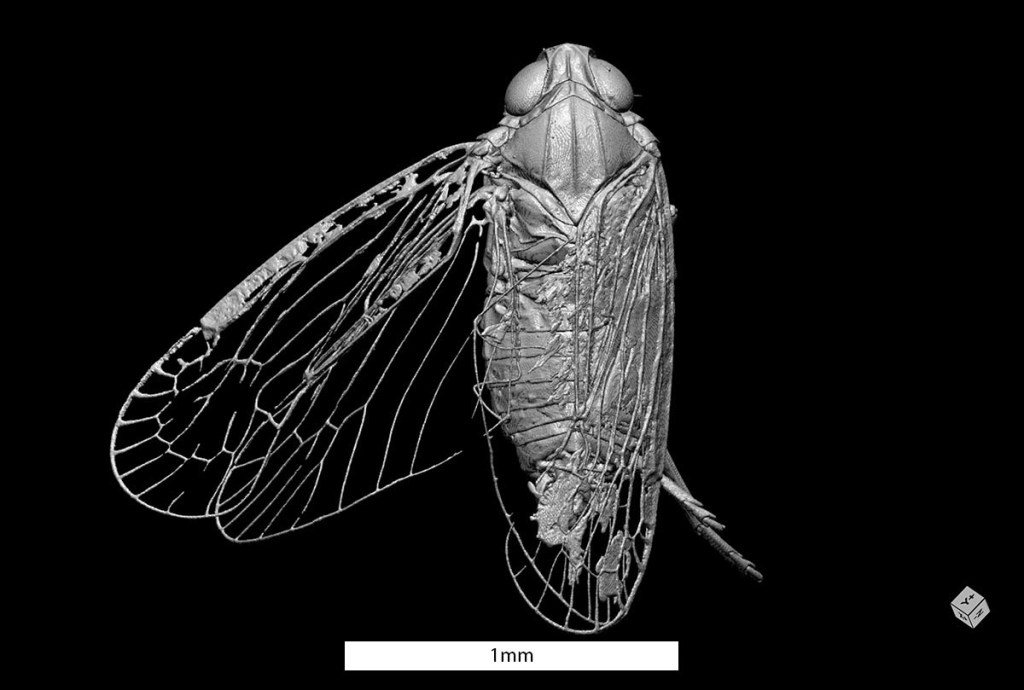

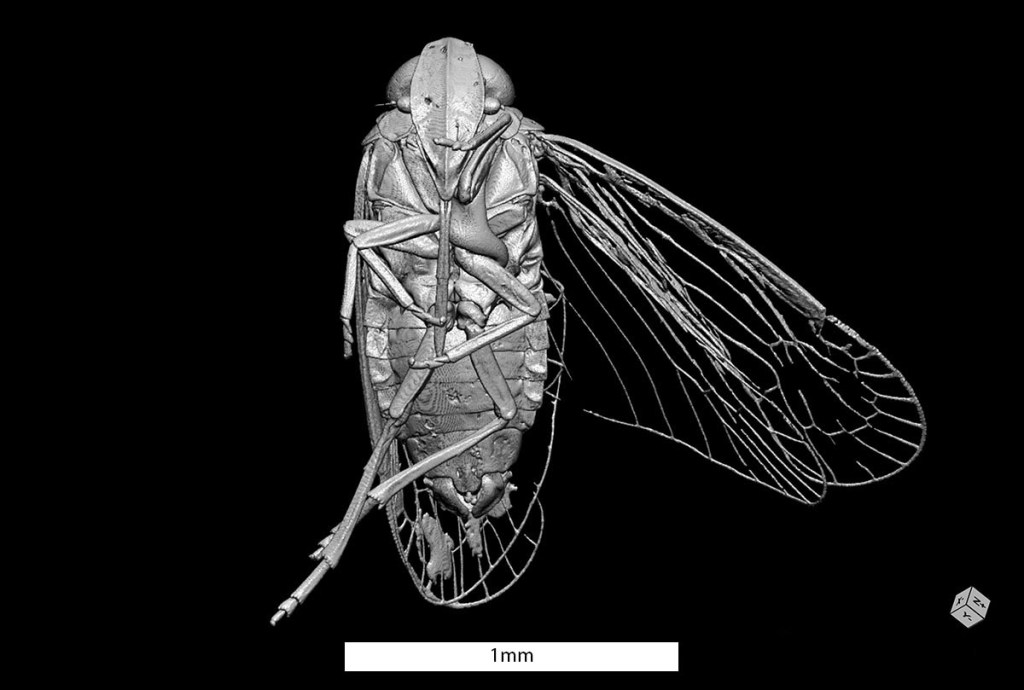

Three-dimensional renderings of a new, yet undescribed species of Achilidae (Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha), preserved in Miocene Dominican amber (~15 million years old). The specimen was scanned at the SOLEIL Synchrotron (ANATOMIX beamline) using Synchrotron X-ray microtomography (SR-μCT). A. Habitus, ventral view. B. Habitus, dorsal view. (© Ancheng Peng & Corentin Jouault)

The resulting datasets will therefore be enormous, so the team has lined up banks of high-powered computers and even machine-learning tools to speed up the laborious task of reconstructing the fossils in 3D.

What emerges won’t just be pretty pictures. These models could rewrite parts of insect evolutionary history. For example, they may uncover the earliest records of certain insect families, refine the timeline of insect diversification, and provide the raw data needed to estimate how extinction and speciation rates shifted during the ATR. In short, these pieces of amber become not just a window into the past, but a testbed for some of the biggest questions in evolutionary biology.

And there’s a democratic twist: all the scans, reconstructions, and 3D models will be made freely available in open repositories. That means anyone, from entomologists to curious hobbyists, could spin, zoom, and explore these ancient insects in digital space.

So, next time you spot an insect hovering around a flower, think of its ancestors locked in amber, their secrets now teased out by beams of light brighter than the sun. The synchrotron doesn’t just illuminate fossils, it illuminates how deep the ties between bugs and blooms really go.

Published by