Crab in the lab

One of the most loved specimens in the Museum is the enormous Japanese Spider Crab. It’s been on display for over 100 years, so it’s unsurprisingly shown serious signs of deterioration. In July, staff in our Life collections decided that the crab should come off display and undergo conservation treatment. Bethany Palumbo, Conservator in Life Collections, took charge of this famous specimen.

The most obvious damage was the loss of colour – the natural carotenoid pigments had completely faded due to decades of continuous light exposure under the glass roof. However, once it was taken into the laboratory for a closer look, Bethany soon realised that there were actually many areas that were fake, composed of old materials such as acidic cardboard, newspaper and even carved wood.

These restoration efforts were causing more harm than good, deteriorating and damaging the natural shell material. The whole specimen was loosely held together with animal glue, PVA adhesive and, in some areas, tough wire which was cutting through the shell.

The first step for our conservator was to check the Museum database for information about the specimen, such as when it was donated and by whom. But unfortunately the specimen has no record, nor is it accessioned into the Museum’s collection. Although frustrating, this was important information. As it had no scientific data, Bethany could give this specimen more extensive conservation treatment, without compromising its scientific or historic integrity.

Bethany decided that treatment would consist of cleaning, the removal and replacement of old, deteriorating fill material and the restoration of colour to the shell, making the specimen true to life. These treatments, with the exception of the cleaning element, would be completely reversible.

Work began by taking the specimen apart to clean and treat each section. Sections were gently vacuumed and a moist cloth used to wipe away 100 years of embedded grime. Bethany removed old fill material, softening it with water vapour to allow it to be easily peeled away.

The next task was to create replacements for the missing sections. Bethany used a combination of acid-free tissue and closed-cell polythene foam. Intricate areas like the claws proved more challenging. Replacements were sculpted free-hand from Plasticine, moulded in silicone and finally cast in Jesomite composite plaster. They now look pretty close to the real thing and are a big improvement on the old wood and paper versions.

Before it was ready to go out on display Bethany replaced the faded colour. Japanese Spider Crabs are bright red and white in life, but ours had become washed out beige.

Photographs of Spider Crabs were used as a reference for the colours, and Bethany also spoke to crustacean experts in the Museum to make sure it was accurate. She used an airbrush and acrylic inks, selected for their high UV resistance. The shell was coated with a barrier layer to allow the ink to be removed in the future, if needed.

Airbrushing the specimen was the most time consuming element, as it required multiple layers and various brushing techniques to make the crab look true to life. Once completed, Bethany gave the crab a final protective coating, providing good water resistance, ready for the next time it needs a good clean!

Rachel Parle, Interpretation and Education Officer

She’s sourced exciting, original looks by cutting edge professional designers. Watch out for explorations of iridescence, dramatic colour combinations and textures that mirror the display techniques used by the flamboyant birds. Changes in the volume of models’ outfits will also reflect the impressive puffed up feathers that male birds use in their dances.

She’s sourced exciting, original looks by cutting edge professional designers. Watch out for explorations of iridescence, dramatic colour combinations and textures that mirror the display techniques used by the flamboyant birds. Changes in the volume of models’ outfits will also reflect the impressive puffed up feathers that male birds use in their dances.

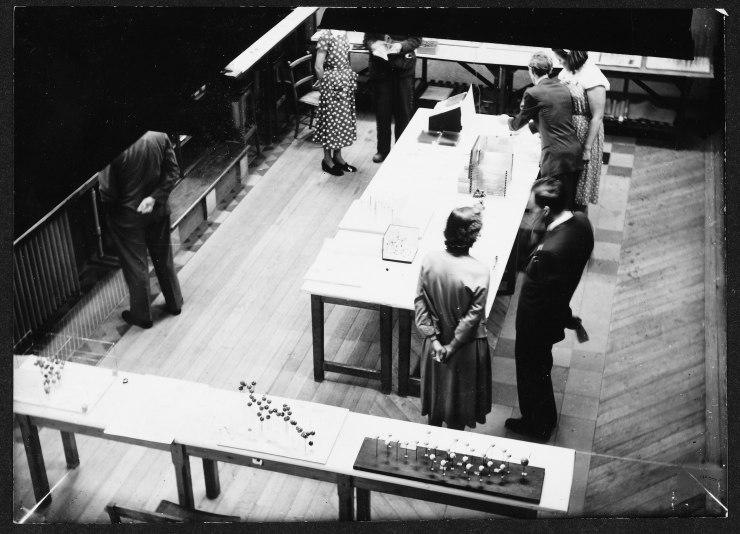

After getting a first class degree in 1932, Dorothy went to Cambridge to do a PhD with JD Bernal. There she began to study biologically important substances such as cholesterol and pepsin.

After getting a first class degree in 1932, Dorothy went to Cambridge to do a PhD with JD Bernal. There she began to study biologically important substances such as cholesterol and pepsin.