John Phillips: A Life in Stone

Lithography and Early Life

You’re 18 years old, an orphan, and your uncle and guardian has just been thrown in debtor’s prison. You have no other family around you. What do you do? Well, if you’re John Phillips (1800–1874), you attempt to run a lithographic printing business out of your uncle’s house; extraordinary for one so young and doubly so as lithography was still a relatively new technology. According to Michael Twyman, in 1819 “the number of lithographic printers in London could still be counted on one hand.”

Engraving vs Lithography

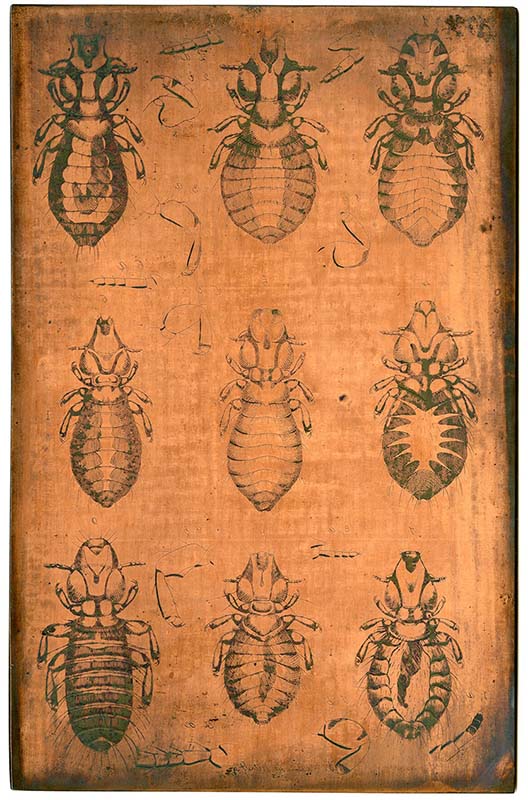

At the time, mass-printed drawings were still commonly engraved on copper plates. It was a time-consuming process. A skilled engraver could take over 40 hours to complete a ten-inch plate and any errors were costly to correct.1

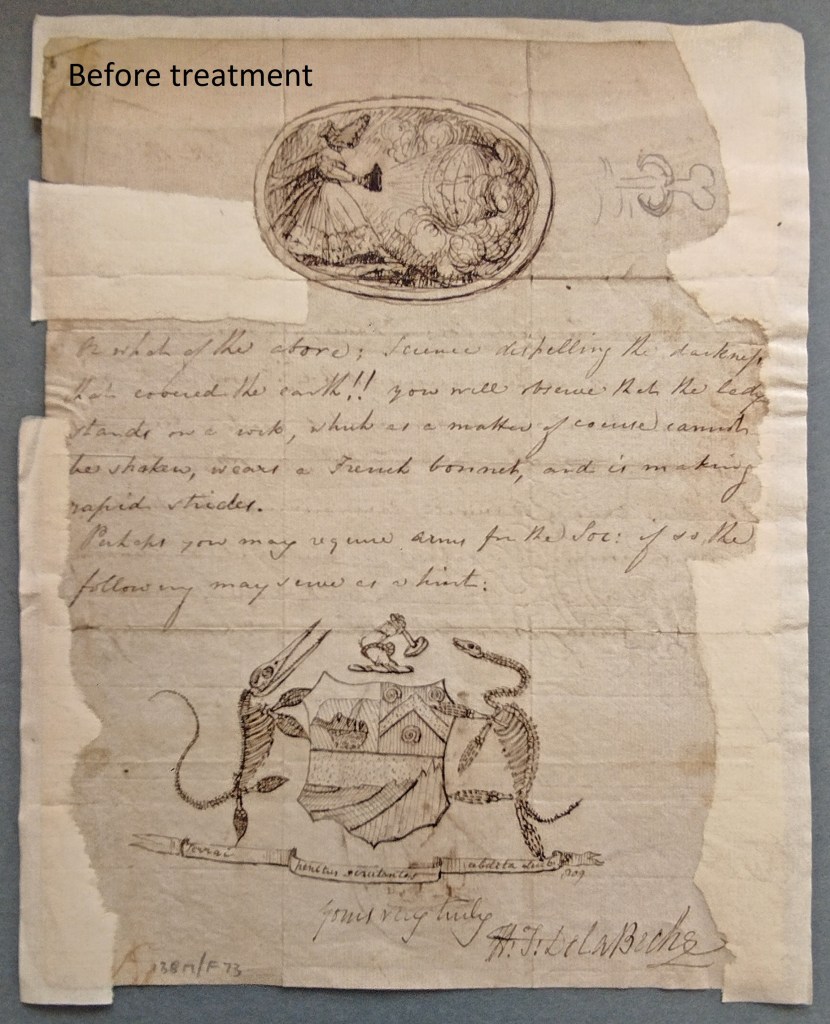

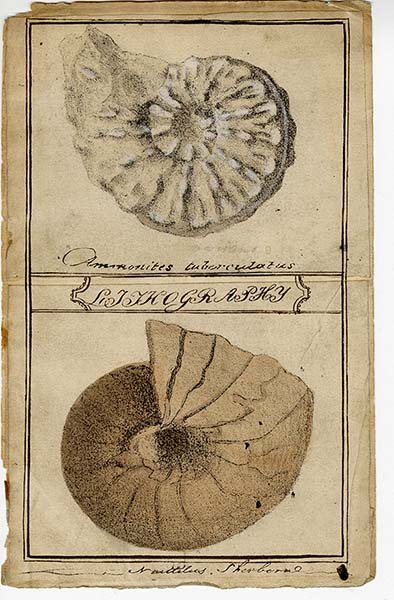

Invented just two decades earlier in 1798 by German playwright Aloys Senefelder, lithography made the process of printing cheaper and simpler. Drawing on a prepared stone surface with waxy ink or chalk and using the repelling properties of fat and water to print the finished design, the need for precise etching was eliminated and errors could be wiped away rather than having to burnish and re-etch a metal plate.

Phillips’ Early Experiments

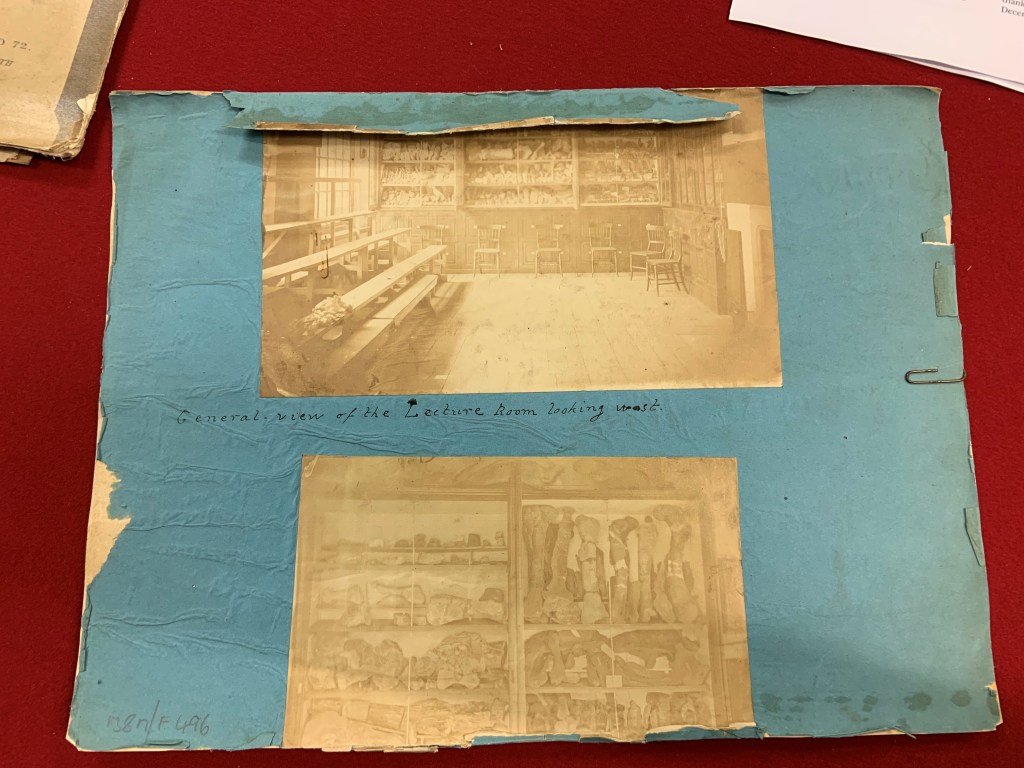

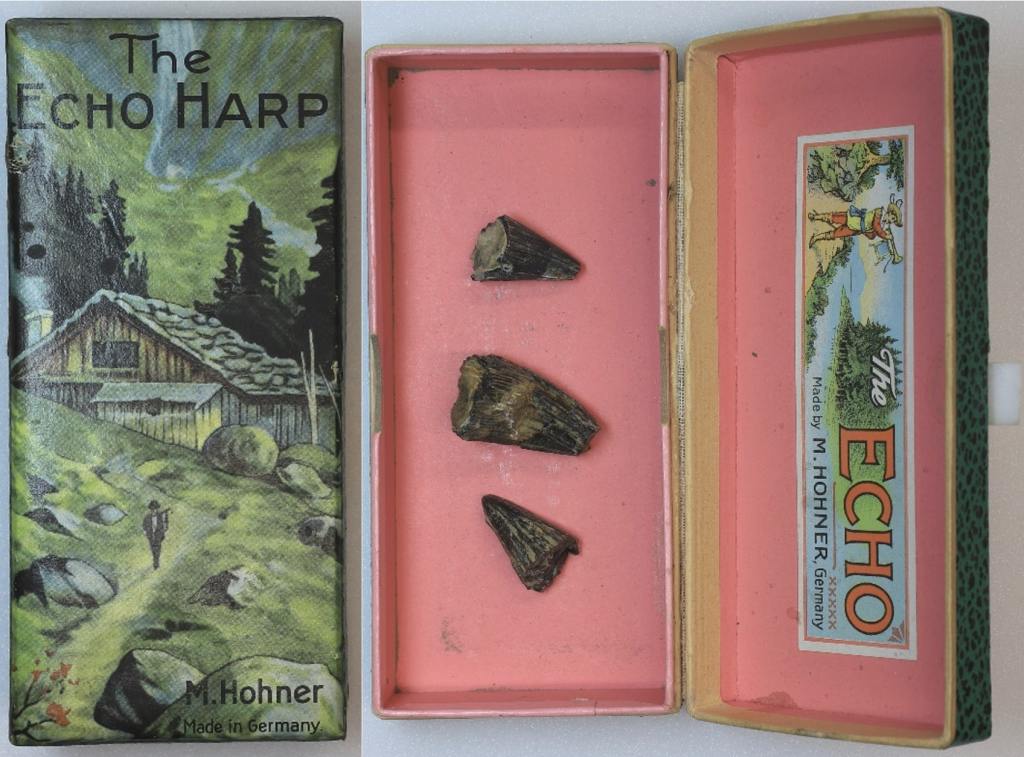

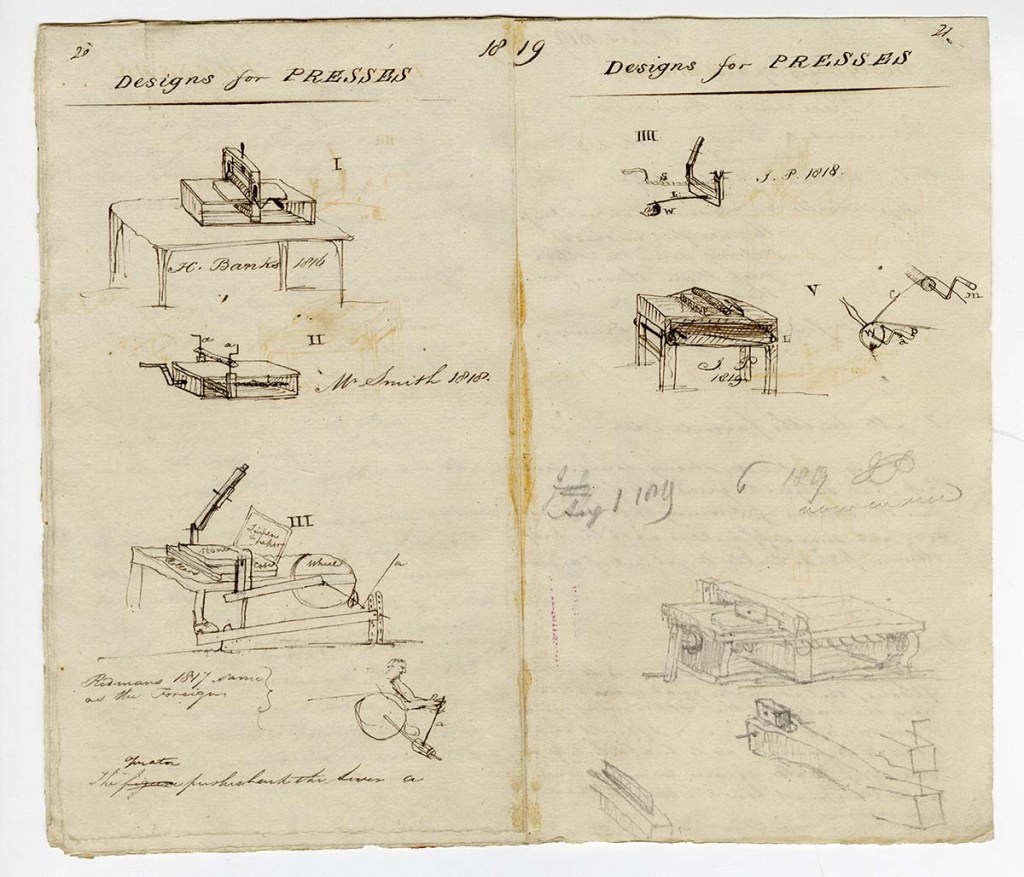

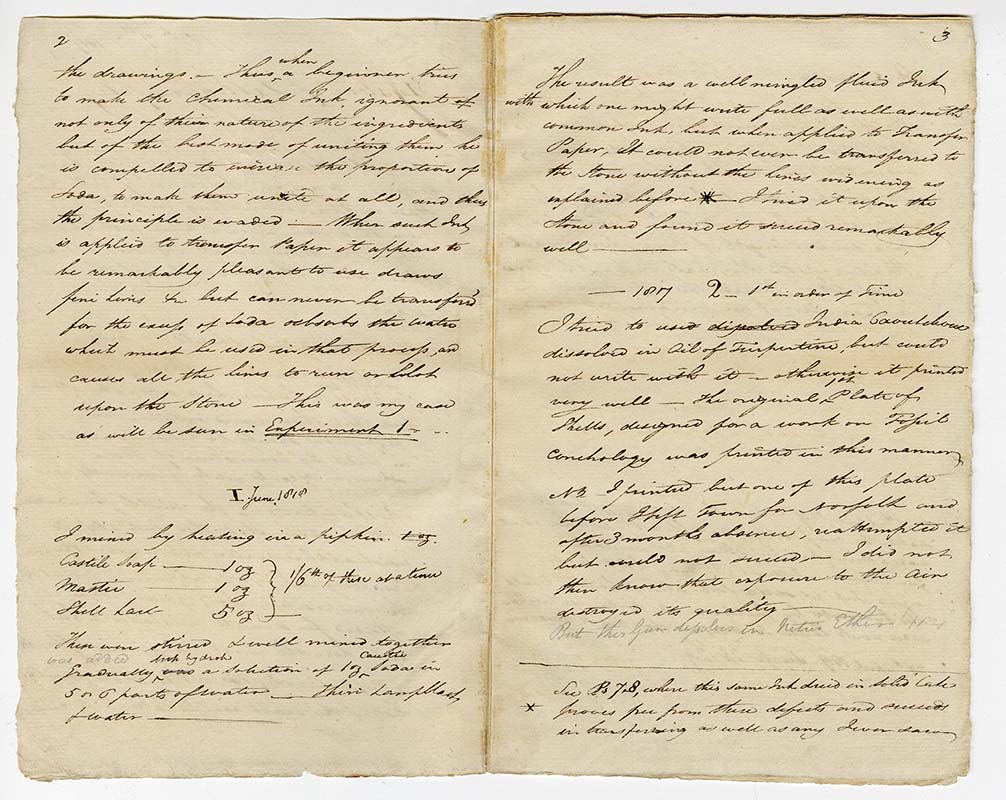

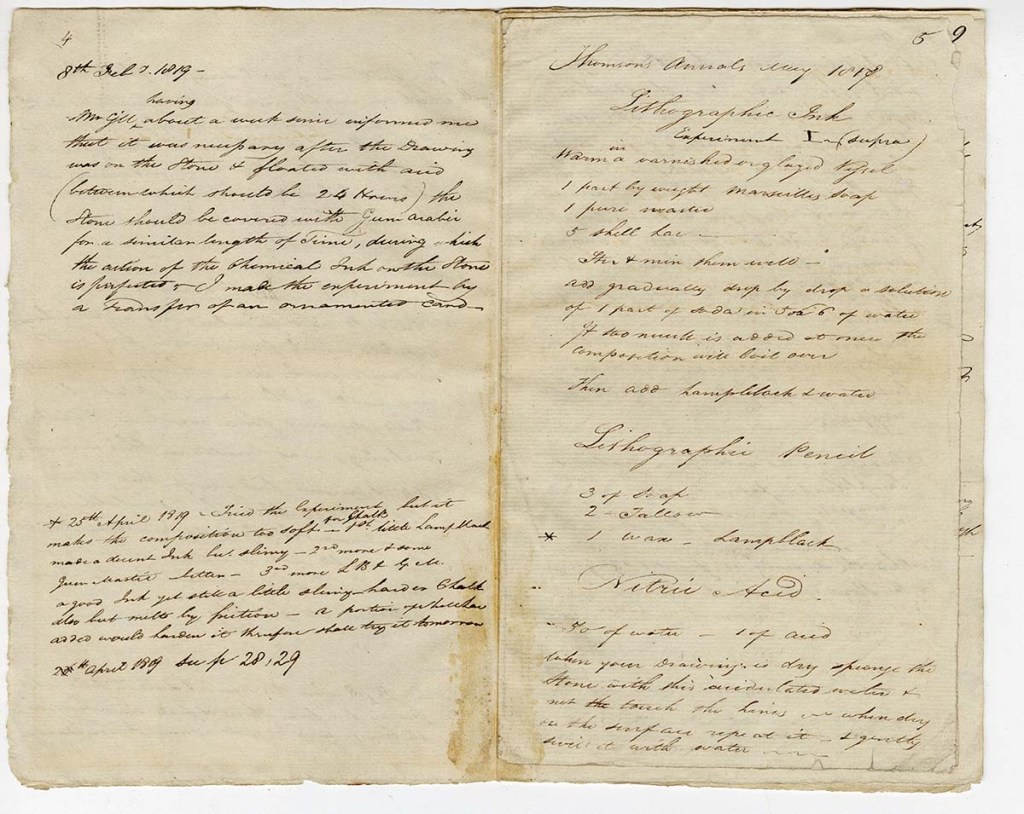

With few works to reference or professionals to consult, Phillips had taken what information he could find and applied himself to testing and recording different ink to chalk ratios for optimal drawing and printing. He even tinkered with existing press designs, trying to invent a more efficient machine. The results of his experiments are preserved today in his notebooks, held here at the Museum.

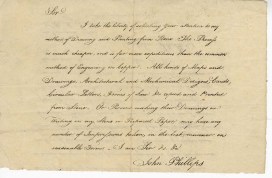

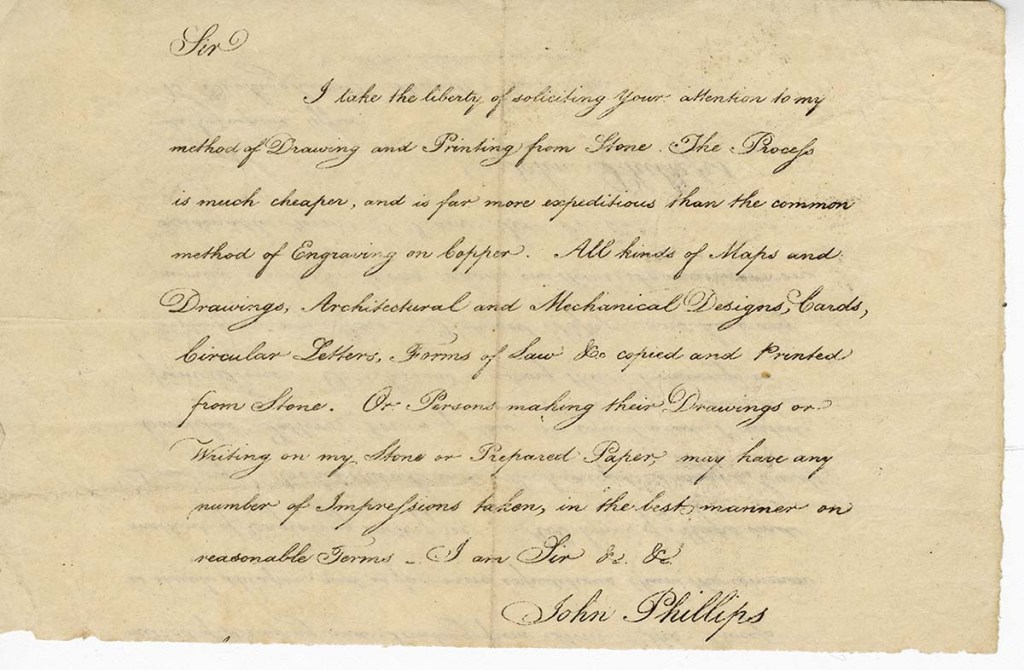

Phillips set up shop in his uncle’s house at 15 Buckingham Street and advertised in a circular, “I take the liberty of soliciting Your Attention to my method of Drawing and Printing from Stone. The Process is much cheaper, and is far more expeditious than the common method of Engraving on Copper.”

Family, Fossils and Geology

Having arrived in London in 1815 to live with his uncle, William Smith—later hailed as the father of English Geology—Phillips had spent much of his youth bouncing from relative to boarding school to family friend. Most recently he had stayed with Smith’s friend the Reverend Benjamin Richardson, an avid naturalist and geologist.

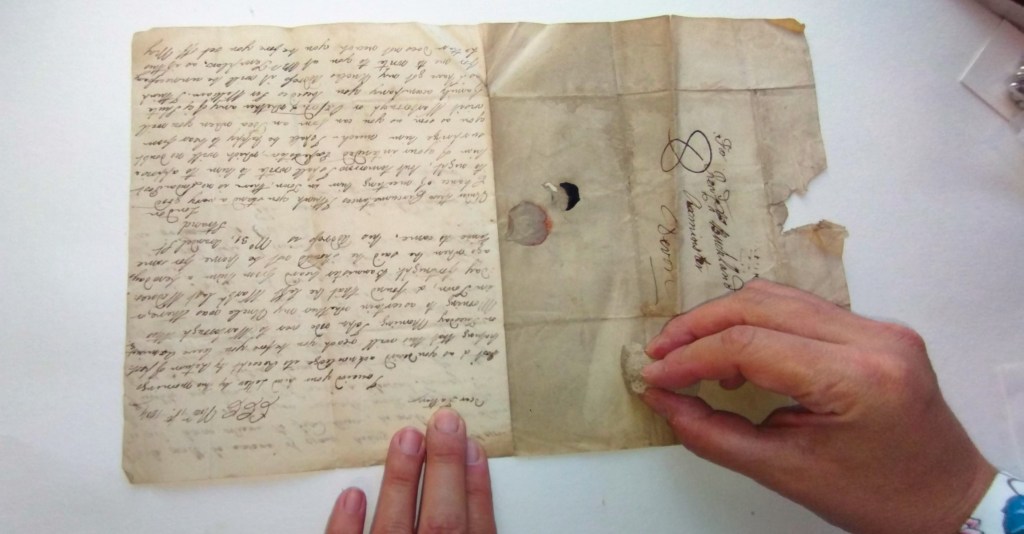

William Smith had just published A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales with part of Scotland…, the first geological map of England and Wales. Smith showed that the relative positioning of specific fossil species in strata could be used to identify the same strata across the UK — a remarkable achievement, but one that nearly ruined him financially. His finances were so desperate that when his nephew arrived he was in the middle of negotiating the sale of his fossil collection to the British Museum.

These same fossils, arranged according to the strata in which they were found, had formed the basis of his great work. Selling them was a huge blow, both personally and professionally; he had collected them himself whilst travelling as a land surveyor, consulted them frequently in his studies, and given access to any scientist wishing to see them. It also meant they would need to be formally catalogued to be useful.

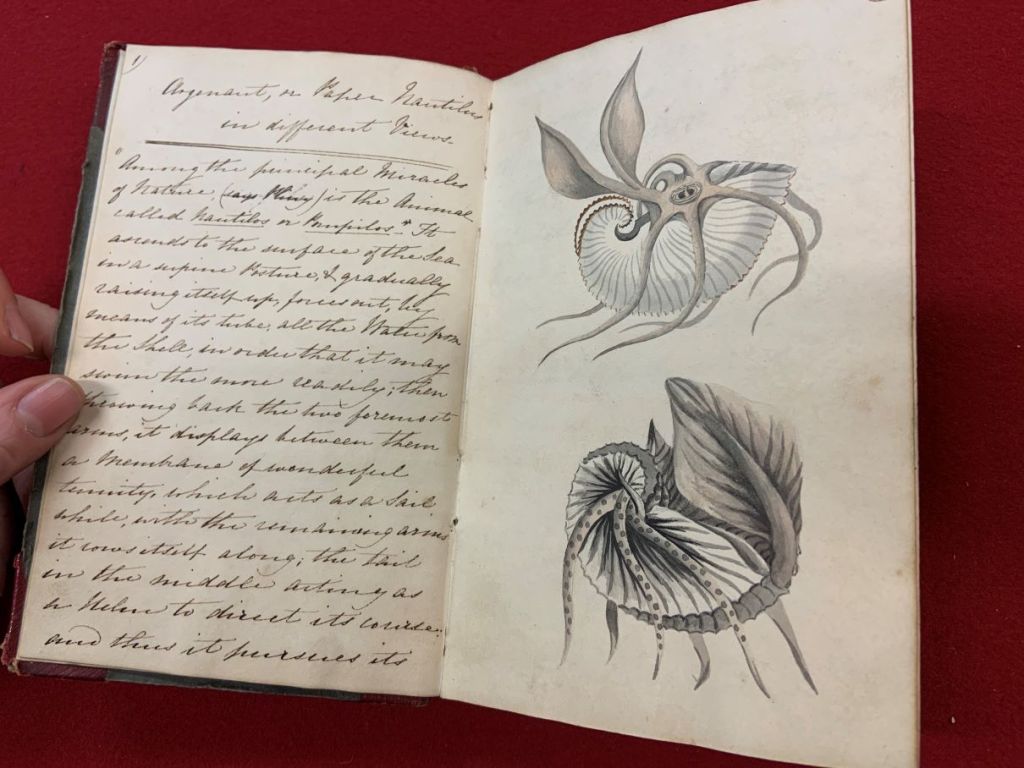

Luckily his newly arrived nephew had a talent for drawing and a keen interest in shells and geology; Phillips had by then begun his experiments with lithographic printing, conscious of the enormous cost savings possible for publications, both for his uncle and his own work on fossil conchology. He became the person Smith needed to assist in drawing, arranging, and cataloguing the fossils for publication before they were crated up and sent away. This led to the publication of Strata Identified by Fossils (1816) and Stratigraphical System of Organized Fossils (1817). It was then that Phillips began experimenting with lithographic printing, conscious of the enormous cost savings possible for publications, both for his uncle and his own work on fossil conchology.

Notebooks, Inventions and Later Life

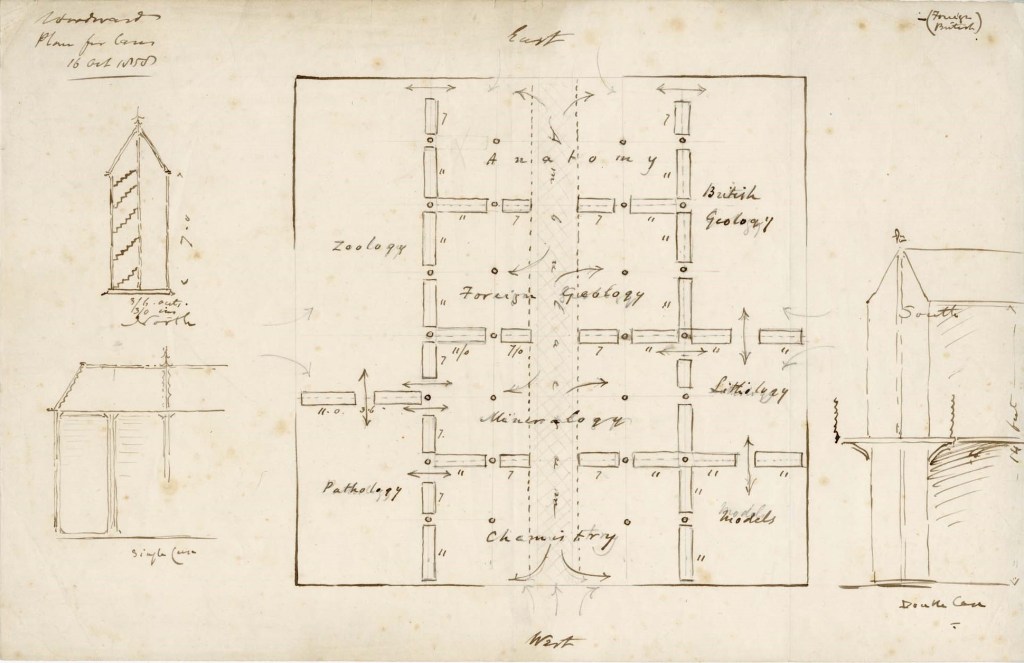

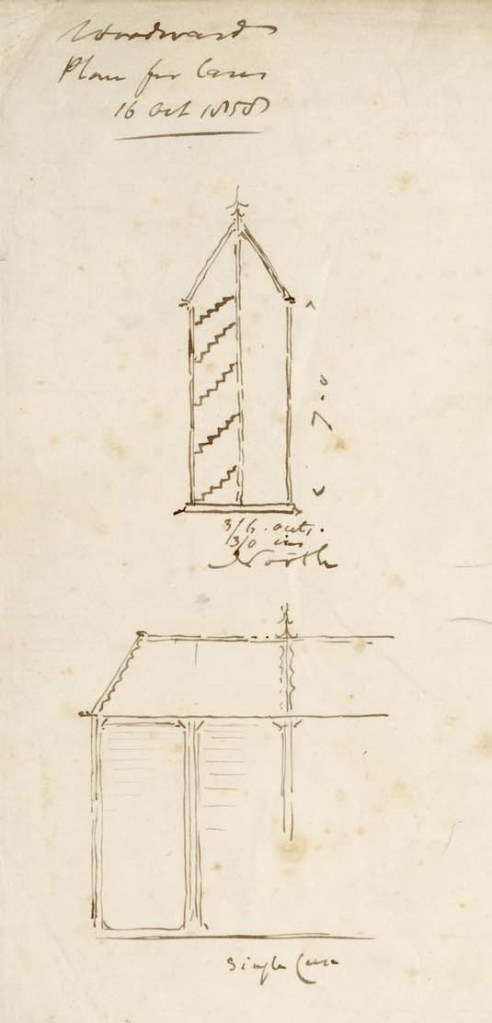

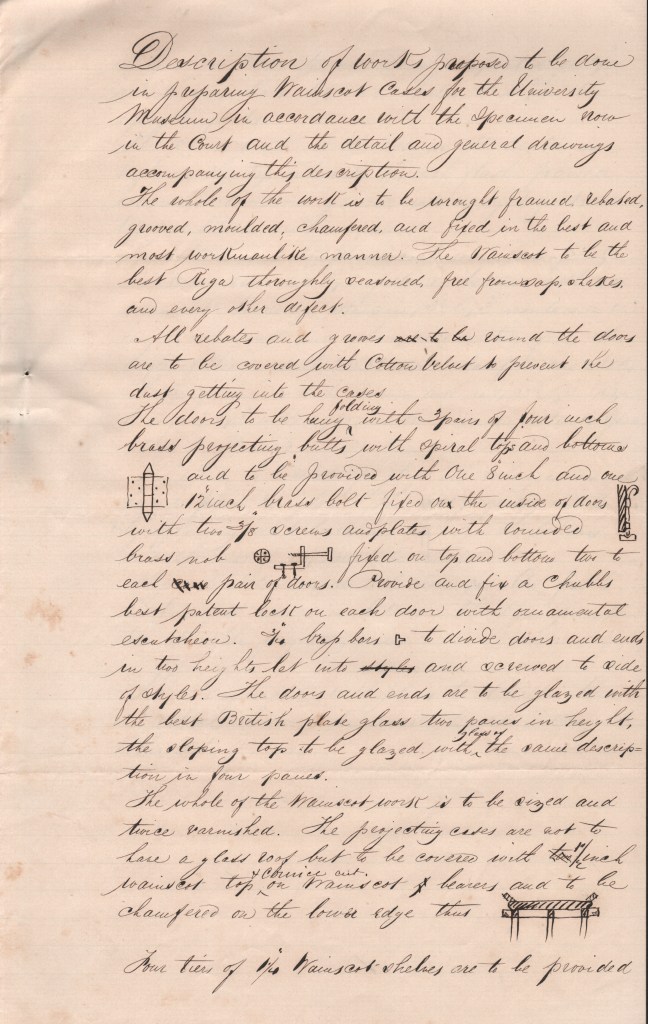

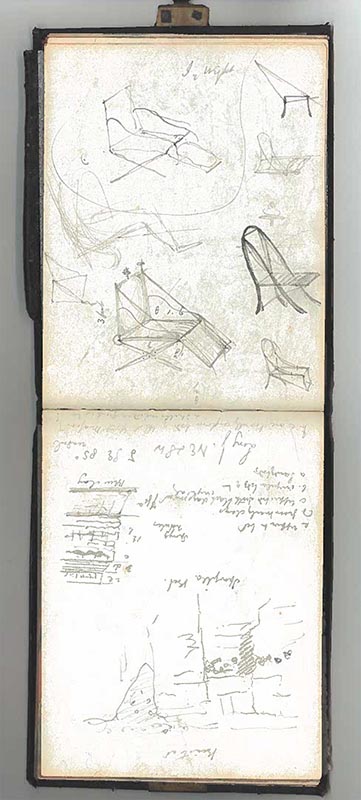

Phillips’ notebooks are filled with detailed observations of natural history from his travels across the UK. They also show his fascination with all things mechanical; doodling whimsical contraptions meant to solve the day-to-day problems of the active naturalist.

With an interest in geology and a fascination with technology, it’s hardly surprising that when Phillips found himself with no support and no money he would see if his interest in lithography or “stone writing” could help with his pressing financial problems. But did it work? Did John Phillips make any money?

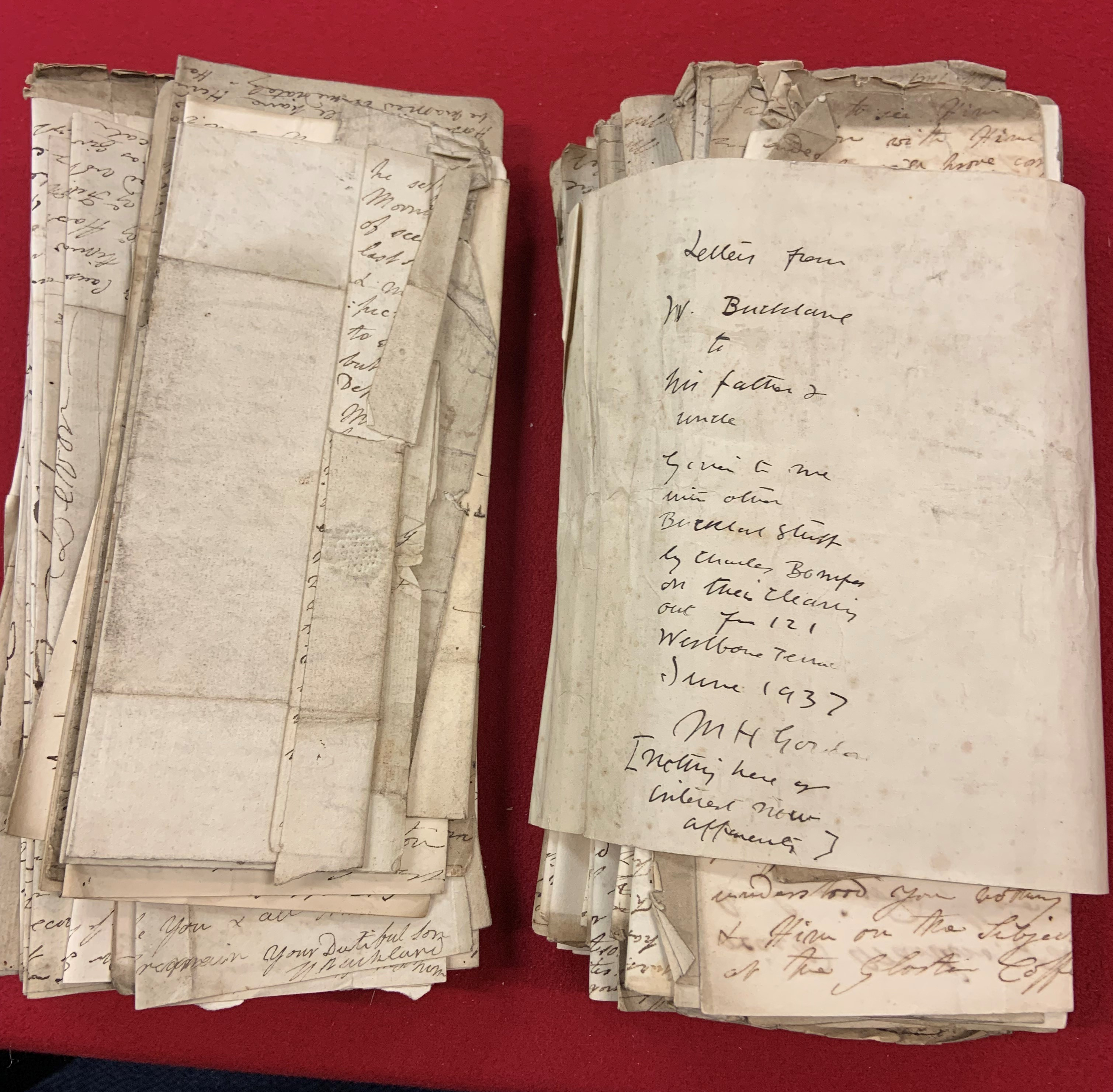

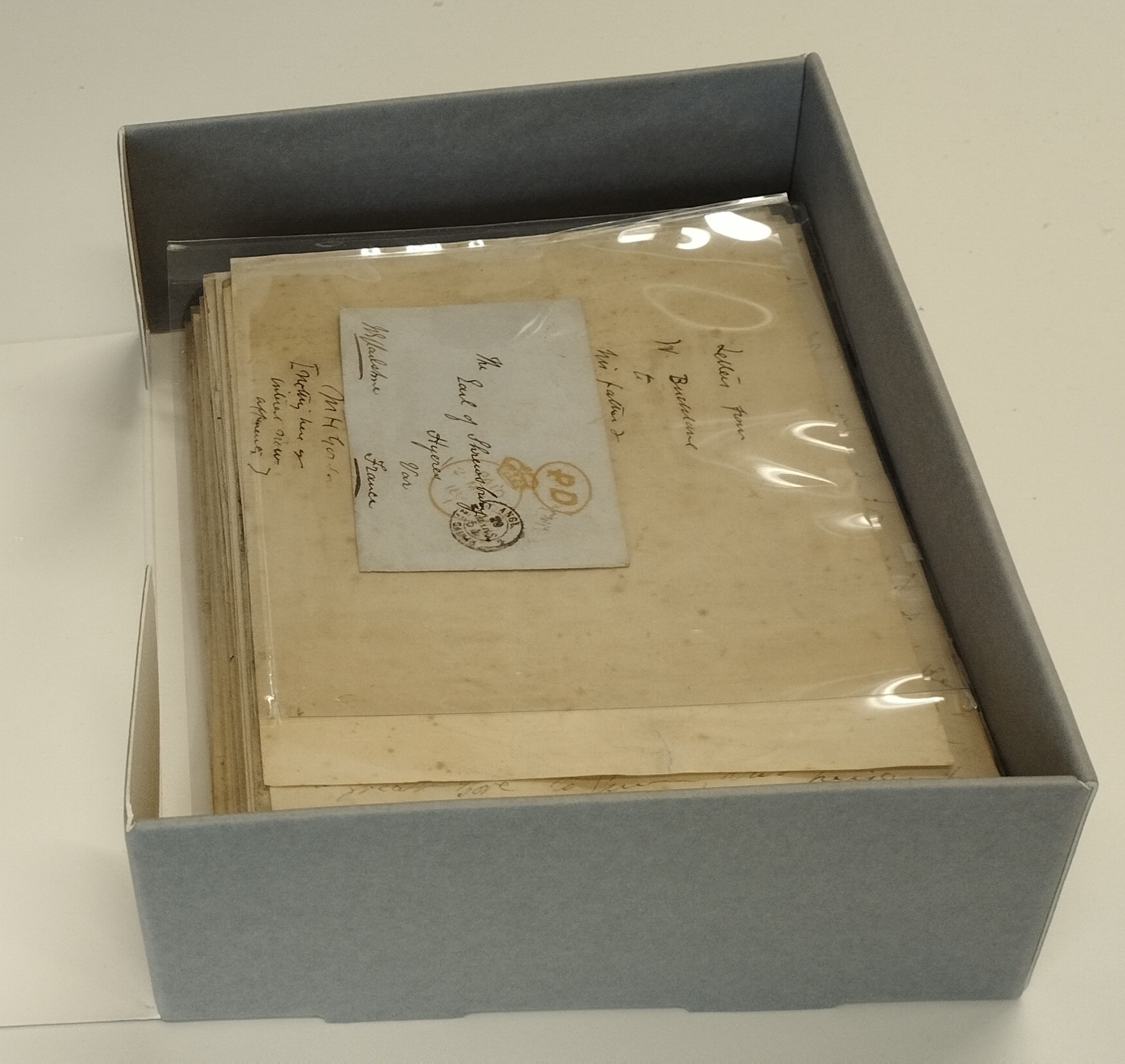

While we hold Phillips’ personal and research papers, sadly no record of sales or responses survive. What we do know is that after William Smith was released from debtor’s prison the house was repossessed and Smith, along with his wife and nephew, left London to eke out a living as itinerant mineral surveyors.

Phillips’ experiment notes

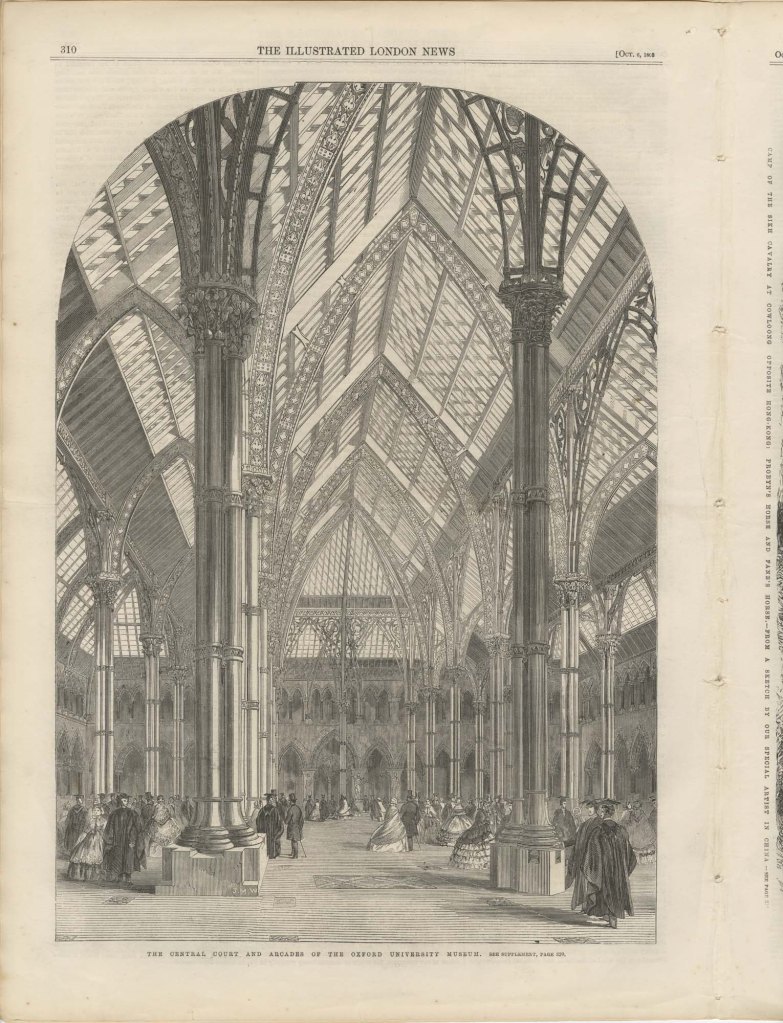

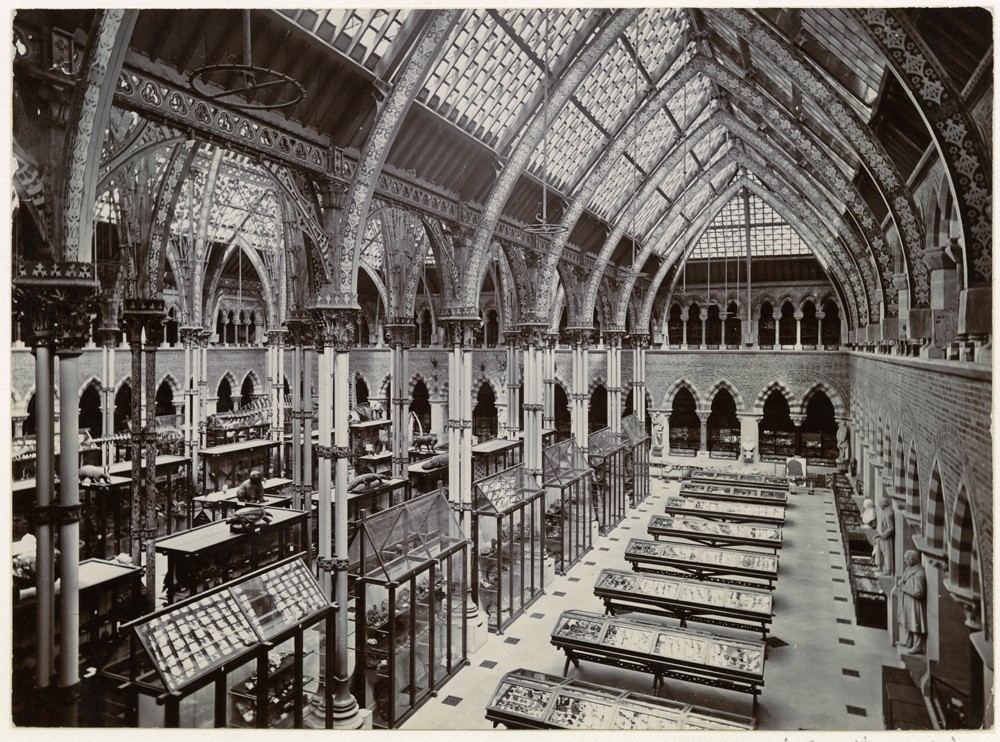

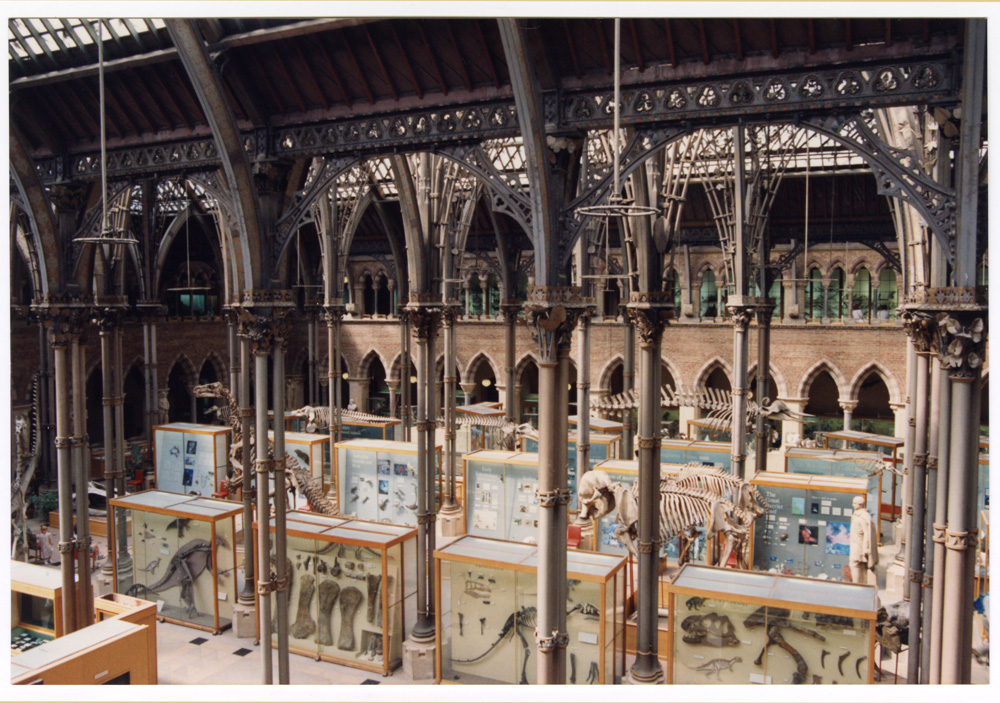

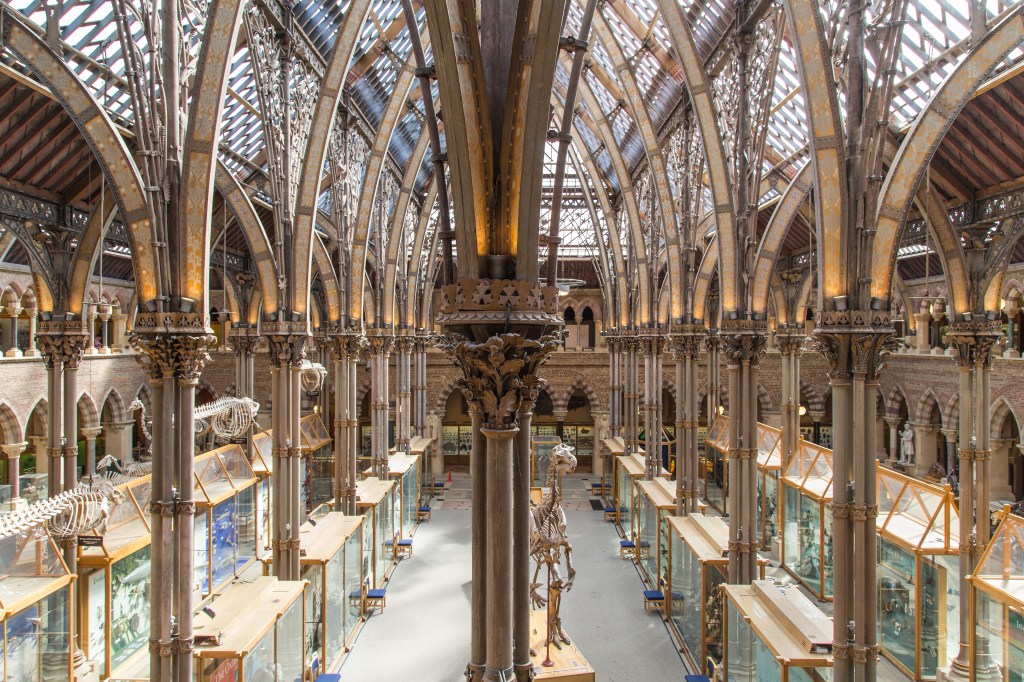

Phillips remained a lifelong advocate for science and technology and went on to become a well-respected geologist, the first keeper of the Museum, and only the second Professor of Geology in Oxford. Tragically, after a convivial dinner on 23 April 1874 at All Souls College Phillips slipped and fell down a flight of stone steps, falling into a coma never to awake.