Boxes, Bags, and Bones

NO, THERE WEREN’T HARMONICAS IN THE JURASSIC!

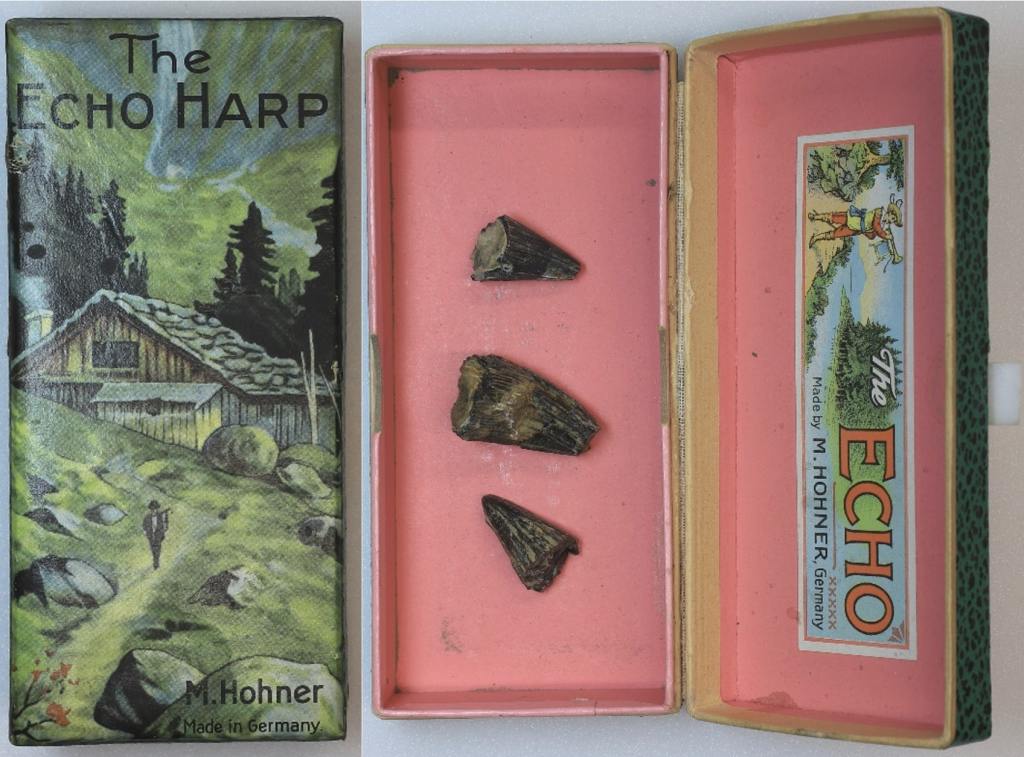

Looking through the collections at OUMNH never gets boring, but sometimes a drawer will open up to reveal something even more eye-catching than the fossils usually found inside. Whilst working on the Museum’s Jurassic marine reptiles a few weeks ago, I came across something particularly surprising: a jewel-green box with a fantastic piece of art on the front. I was instantly intrigued and reminded of all the other times I had encountered a holder as fascinating as the specimen inside it.

Storage in museum collections is an ongoing pursuit of balance between ideal environmental conditions, specimen accessibility, and efficient use of space. This balance applies to all levels of storage: from building to room, cabinet to specimen tray. OUMNH’s Earth Collections are stored in conservation-grade, acid-free boxes or trays made of plastic or cardboard. These boxes are sometimes layered with low-density foam or ‘plastazote’ which can be carved to fit the specimen and keep it from being jostled or damaged. Holders with lids can also provide a micro-environment for specimens to help minimise their exposure to changes in humidity and temperature. The use of these standard materials not only helps protect specimens from degradation but can also deter pests from harbouring in collections spaces.

However, historical collections like those at OUMNH may retain holders that are not standard use. Sometimes, a clean and empty plastic Ferrero Rocher box is the perfect size for that small mammal skeleton that needs storing! Other times, an unusual holder might have been the only thing a field collector had on hand to transport a specimen to the Museum.

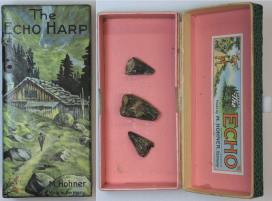

One example of an unusual specimen holder is this ‘Echo Harp’ box by pre-eminent German harmonica manufacturer Hohner, likely from the 1960s. The box no longer holds a harmonica, but instead accompanies pieces of Jurassic pliosaur teeth from Weymouth, Dorset. Pliosaurs were a kind of carnivorous marine reptile related to plesiosaurs, with four flippers, and long tails and necks. If they hadn’t gone extinct in the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago, perhaps they would have come to appreciate the harmonica and its artistic packaging!

Aside from their artistic value, museums may sometimes retain unusual holders because they contain primary source information on the specimen. One such example is a ‘Bryant and May’s Patent Safety Matches’ box in our Earth collections, bearing a packaging design from the early 1900s. The box actually houses a chicken tarsometatarsus bone excavated from “High St. New Schools” in Oxfordshire and is accompanied by a label which describes the particular layer of gravel the specimen was found in — important information for any archaeological or palaeontological find. Although the specimen is stored alongside Pleistocene fossils (10,000 – 2.6 million years ago), chickens did not originate in the UK, so the bone is likely from much more recent times. Someone still must have thought it was important enough to keep in its own special holder!

Similarly, this ‘Tate and Lyle Granulated Sugar’ paper bag features a handwritten original notation in blue pen on the outside. The bag originally contained a specimen found in a collection of Jurassic gastropods and bivalves from Somerset, with the handwriting describing the fossil’s stratigraphic information. The bag also features a recipe for cinnamon apples on the reverse, which we have yet to try!

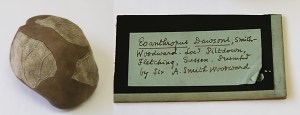

In addition to primary source information, original holders may also provide specimens with provenance. This ovular wooden box filled with organic stuffing material originally contained Quarternary fossil specimens found in Peak’s Hole, Derbyshire. The Museum archive also holds a handwritten letter describing the specimens inside the package and how they were found. The letter dates to 1841 and is addressed to Oxford University’s first Reader in Geology, William Buckland. The specimen holder forms part of a group of objects with such a strong interconnection, and such strong documentation, that retaining the box is a matter of course.

All in all, it’s great that we’ve come so far in the advancement of safe and stable housing for specimens. At the same time, it’s always fascinating to see what else has made its way into collections, just by nature of being able to hold things, either for a short time or a long one. Despite living in the Earth Collections – among fossils, rocks, and the geological past – these objects offer us a little bit of human history too.

By Brigit Tronrud, Earth Collections Assistant