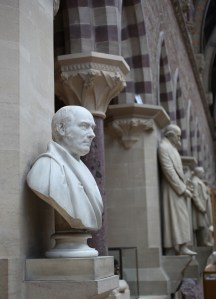

‘Father of English geology’

by Kate Diston, Head of Archives and Library

Today marks the 247th birthday of William Smith. “Who’s he?”, you may well ask. William Smith is perhaps one of the least well-known, yet very significant, figures in the history of the science. Among other things, he created the very first geological map of England and Wales, 200 years ago.

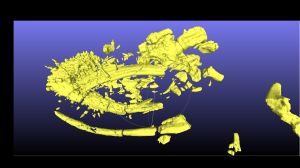

Smith’s work as a land surveyor and mining engineer in the early days of the Industrial Revolution allowed him to understand first-hand how the layers, or strata, of rock beneath the earth are related to those above and below them. From this, he realised you could predict those three-dimensional layers in other locations and also represent the whole thing on a two-dimensional map.

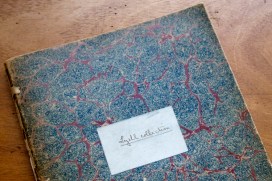

If you visited us in the past few months you may have seen lots of Smith’s maps and other material in Handwritten in Stone, our special exhibition which celebrated his life and work. Now, a new exhibition featuring copies of items from our collections is opening in Smith’s birthplace of Churchill, Oxfordshire.

The displays at the Heritage Centre in Churchill take a very different look at the ‘father of English geology’, offering a rare glimpse of Smith’s personal correspondence with his family.

In honour of Smith’s birthday, we showed off his most famous work, the beautifully coloured 1815 map, in front of his bust in the Museum court today. As one of the Museum’s treasures not normally on display, it is a real treat to see it being admired by visitors.