Of Jumping Mice and Megalosaurus

CELEBRATING THE RECENT ACQUISITION OF AN IMPORTANT ARCHIVE

By Danielle Czerkaszyn, Librarian and Archivist and Grace Exley, AHRC Doctoral Student

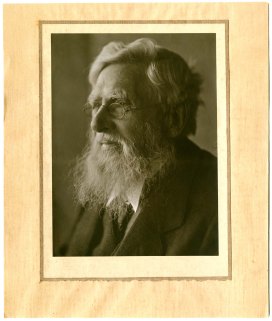

200 years since the first scientific description of a dinosaur, the Museum has welcomed a significant archival collection relating to the man who introduced us to Megalosaurus, William Buckland (1784-1856). The archive contains over 1,000 items including letters, notebooks, family papers, prints, and artworks. It joins the Museum’s existing Buckland archive, as well as more than 4,000 geological specimens, and helps fill in the knowledge gaps surrounding the life and work of Oxford’s first Reader in Geology and Mineralogy. Not only is there the potential to learn more about Buckland’s early life as a student at Christ Church, there is also material relating to the wider Buckland family, including his son, the zoologist Francis Trevelyan Buckland, and wife, the naturalist Mary Buckland (née Morland, 1797-1857).

Among the 70 letters in the archive that are addressed to Mary, there is correspondence from chemist William Wollaston, Scottish polymath Mary Somerville, and a lively letter from John Ruskin, explaining to Mary his disgust at all things marine:

“I dont [sic] doubt that those double natured or no-natured salt water things are very pretty alive, but they disgust me by their perpetual gobbling and turning themselves inside out and on the whole I think for purple and rose colour & pretty shape, I may do well enough with convolvulus’s [sic] & such things which dont [sic] eat each other up, backwards & forwards all day long.”

Ruskin was clearly teasing his friend, as molluscs happened to be Mary’s specialist subject!

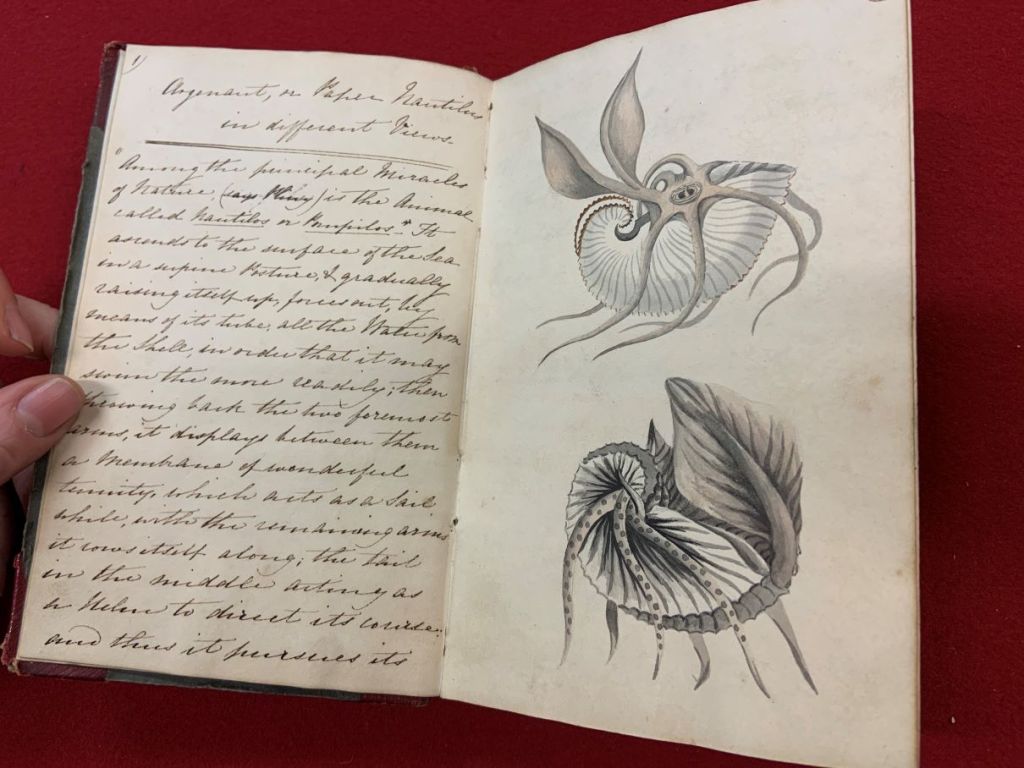

The collection also contains two sketchbooks belonging to Mary, one of which dates from June 1817, seven years before her marriage to William and contains exquisite ink and watercolour illustrations of natural history specimens.

The sketchbook gives us a rare glimpse into how a nineteenth-century woman learned about natural history. The book contains copied passages from natural history texts, enabling us to trace what Mary was reading. Her interests spanned geology and mineralogy, and she also included pieces on zoological curiosities and even polar exploration. She read and copied extracts from a variety of sources, some of which – George Shaw’s Zoological Lectures, for example – were intended to suit a lay-audience (as Shaw put it, intended as a “familiar discourse with Lady-Auditors”). However, other elements of her reading were probably never intended for a woman like Mary — she also copied passages from the Transactions of the Geological Society even though women could not join as Fellows until 1919. As archival materials relating to women are often sparse, this is a truly rare and incredibly valuable insight into how Mary used her connections to access resources and the techniques she used to teach herself about natural history.

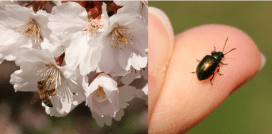

Perhaps the most striking feature of the notebook is its intricate, exquisite illustrations. These, done in watercolour, ink, and pencil, are reproductions of the figures from the works Mary copied out. A favourite in the sketchbook is the “Canadian Jumping Mouse”, a long-tailed rodent described in a piece in the Transactions of the Linnaean Society by Major General Thomas Davies in 1797. There are also many representations of molluscs (detailed enough to repulse Ruskin), mineral specimens, and occasional fold-out geological sections. As we flick through the book, we can see Mary experimenting with media and techniques — not only developing as an artist but also honing her skills as a scientific illustrator.

The skills and knowledge Mary developed in her natural history notebook were crucial to her later collaboration with William, as well as her own independent work as a draughtswoman before her marriage. In 1824, when Buckland presented the jaw of Megalosaurus to the Geological Society, it was “M. Morland” who provided the painstakingly detailed plates. Research has begun to uncover the extent of Mary’s work as a naturalist and illustrator, and now, with the help of the materials in the newly acquired archive, we can explore the origins of her skills. The archive is currently in the hands of a Paper Conservator, Anna Español Costa, to ensure the material is kept in the best condition for many years to come. Items from the archive will feature in the Breaking Ground exhibition, opening in October 2024.

Our fundraising campaign saw us receive generous support from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, Arts Council England/V&A Purchase Grant Fund, Friends of the National Libraries, Headley Trust, and other private donors. Additionally, in late 2022, we launched the Buckland Papers Appeal, asking members of the public to help us meet our target to purchase the archive. Thank you to all our funders and members of the public who responded to our call. We could not have raised the money so quickly without your support and we are now thrilled to share the archive with you all.