What’s on the van? – Trilobite

This week’s What’s on the van? comes from Dr David Legg, Post-doctoral Research Fellow in the Museum’s Earth Collections.

This particular trilobite specimen (Acaste inflata) was collected and named by John William Salter during the Ledbury Railway Tunnel cutting in 1864. Salter worked with many famous scientists during his career; he was an apprentice of the famous mineralogist James De Carle Sowerby, before becoming a curator for Adam Sedgwick at the Woodwardian Museum in Cambridge (now the Sedgwick museum), and in his later years he assisted Roderick Murchison on his work on Siluria. During this time, Salter developed an interest in the trilobites of Wales and was considered a world expert on this group.

Trilobites are a group of arthropods (the group that includes spiders, scorpions, crustaceans, insects, etc.) characterised by the possession of a hard exoskeleton composed of calcium carbonate. They are some of the first animals with hard parts found in the fossil record. The first trilobites appeared roughly synchronously on various continents around 520 million years ago, and went extinct during the largest mass extinction of all time at the end of the Permian (c. 251 million years ago), nearly 20 million years before the first dinosaurs appeared.

Acaste inflata belongs to a group of trilobites called the phacopids. The eyes of phacopid trilobites are unlike any others in the animal kingdom. The eye may consist of over 50 lenses, each separated from the next by a thick interlenticular cuticle. Because there are no modern animals with similar eyes it is unclear how they functioned to produce a clear visual image, however, the shape of each individual lens meant it was capable of focussing on objects of varied distance without the need for any additional focal mechanism (like the human lens which needs to change shape in order to see objects of different distances).

This picture is a bit strange because the trilobite is enrolled (curled up like a woodlouse) and the view is of the top of the head. We assume that this was a form of defence used by most trilobites.

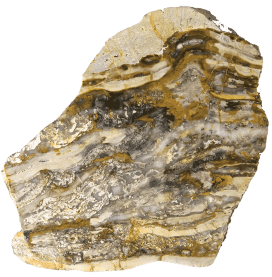

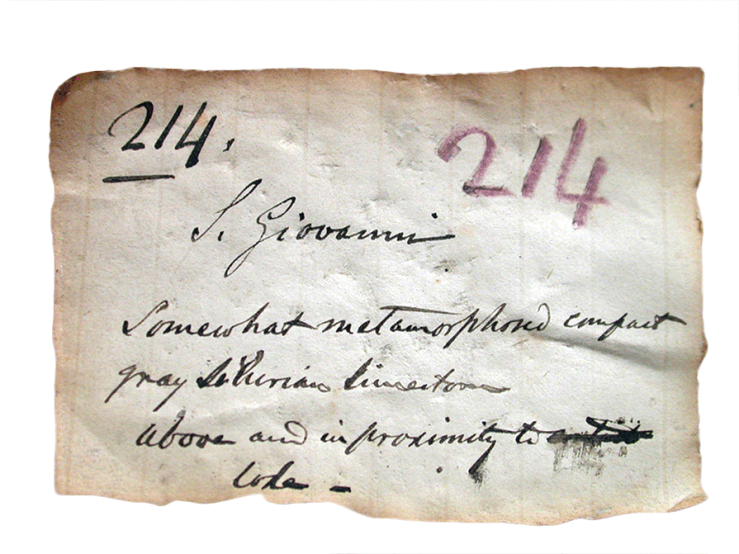

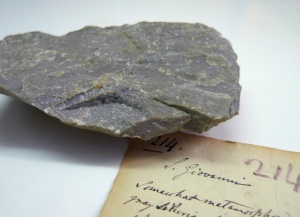

William Jervis wrote books on the rocks and minerals of Italy that are important for ores, building materials and water supplies. He also put together sets of rocks samples to be sold to other museums and universities. He trimmed each one to a neat rectangular shape and gave it a number. On the label, he’d write the number, what the rock was, and exactly where it was collected. Some of his labels are very detailed indeed and show that his samples came from places no longer accessible today. The specimen accompanying this label is one of a set of Sardinian rocks. It comes from San Giovannni mine, near Iglesias, and shows the kind of grey limestone that was found close to the ‘lode’, the vein of lead and zinc ore minerals which was being worked by the miners.

William Jervis wrote books on the rocks and minerals of Italy that are important for ores, building materials and water supplies. He also put together sets of rocks samples to be sold to other museums and universities. He trimmed each one to a neat rectangular shape and gave it a number. On the label, he’d write the number, what the rock was, and exactly where it was collected. Some of his labels are very detailed indeed and show that his samples came from places no longer accessible today. The specimen accompanying this label is one of a set of Sardinian rocks. It comes from San Giovannni mine, near Iglesias, and shows the kind of grey limestone that was found close to the ‘lode’, the vein of lead and zinc ore minerals which was being worked by the miners.

It’s time for one of the stars of the Museum’s collection! One of our most famous specimens, the dodo even features on our logo.

It’s time for one of the stars of the Museum’s collection! One of our most famous specimens, the dodo even features on our logo.

![_LEPI1997l[1]](https://morethanadodo.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/lepi1997l1.png?w=740)