A Seed of Doubt

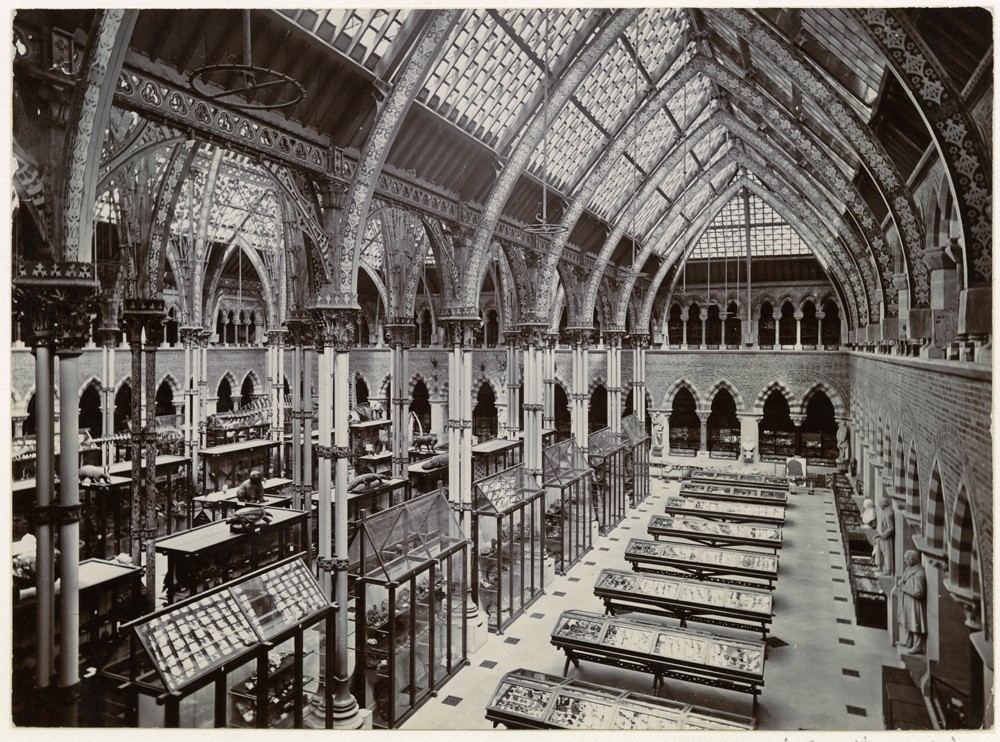

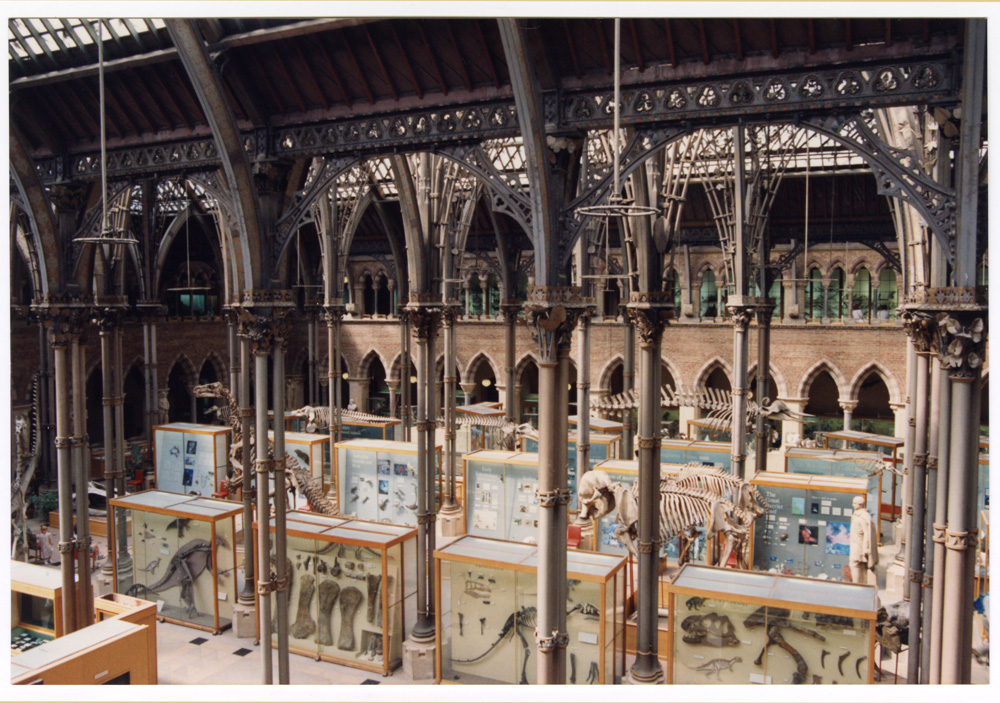

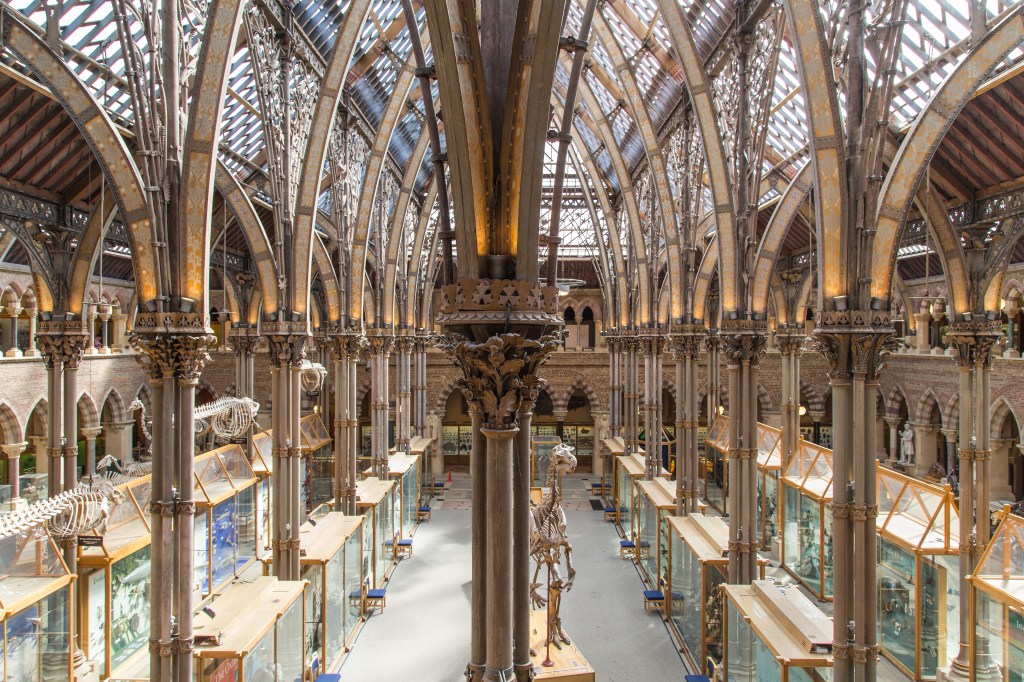

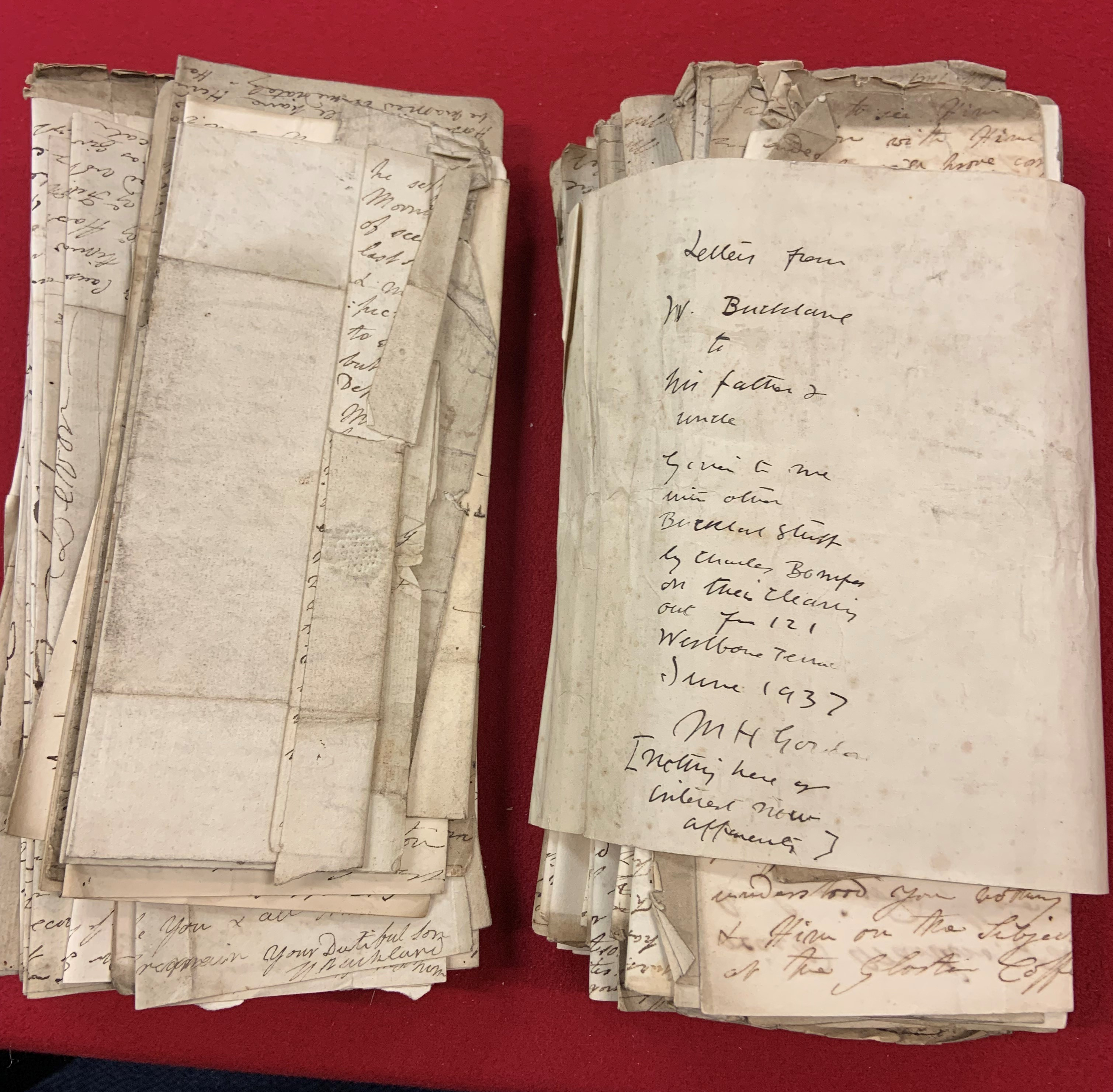

In February 2023, the Museum was lucky enough to acquire an important historical archive – a collection of notes, correspondence, artworks, photographs and family documents belonging to geologists William and Mary Buckland. But before the archive can be enjoyed by visitors and researchers, it must first be cared for, ensuring its preservation for generations to come. Thanks to generous funders, the Museum was able to hire a Project Paper Conservator, Anna Espanol Costa. Considering the Museum had not had a paper conservator since the mid-1990s, Anna was incredibly resourceful with her use of tools and materials, utilising everything from makeup sponges and soft brushes to tweezers and dental picks. In this blog post, we share insights from the eight months she spent assessing, cleaning and repairing some of the most at-risk and important material in the archive, as well as some unexpected surprises she found along the way…

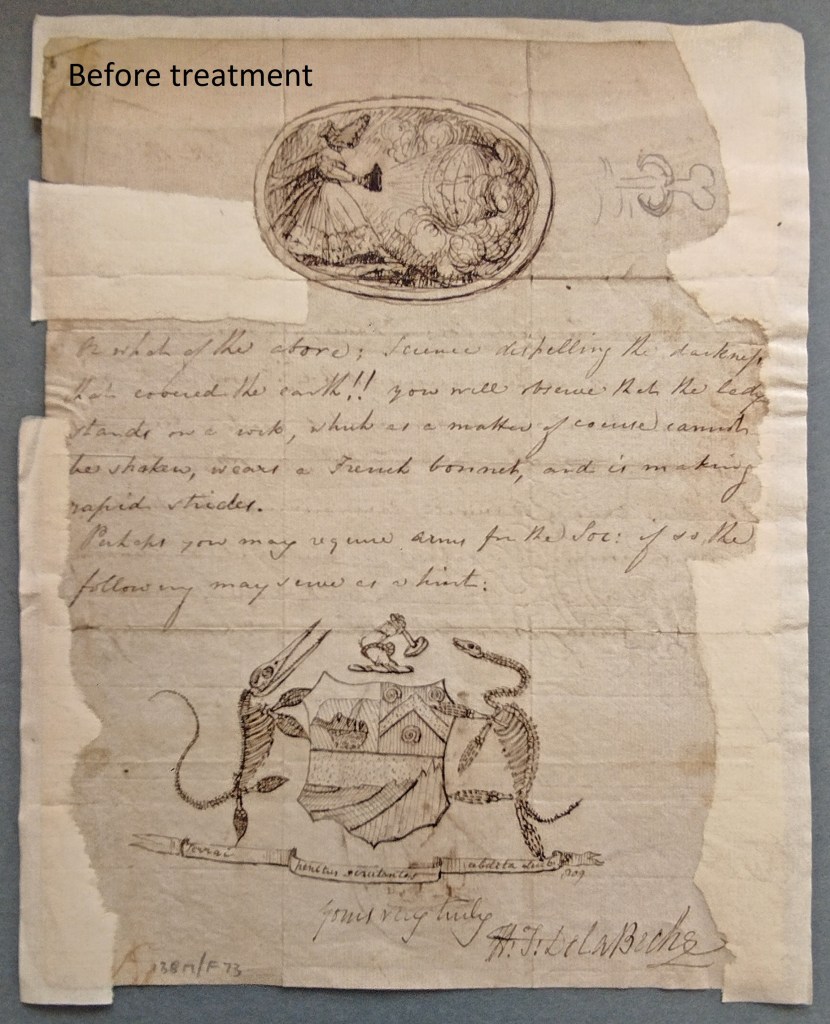

Paper can be used to store information for decades, if not centuries, but it is still vulnerable to frequent handling and poor environmental storage conditions. When the Museum acquired the Buckland archive it was around two hundred years old and, unsurprisingly, many of its items needed care and restoration. Over the years, the papers had been housed in the standard file folders and boxes you would use for office documents, rather than an important historical archive. Many of the folders were overcrowded and had been tied together with string. Some manuscripts had been damaged due to too many items being stored in the same folder, and there were places where the string had cut into the larger pieces of paper causing tears. The most fragile and vulnerable items showed signs of chemical and physical damage, including iron-gall ink corrosion; chemicals in the ink had started to eat through the paper, causing cracks and loss of ink, and consequently text, in some areas.

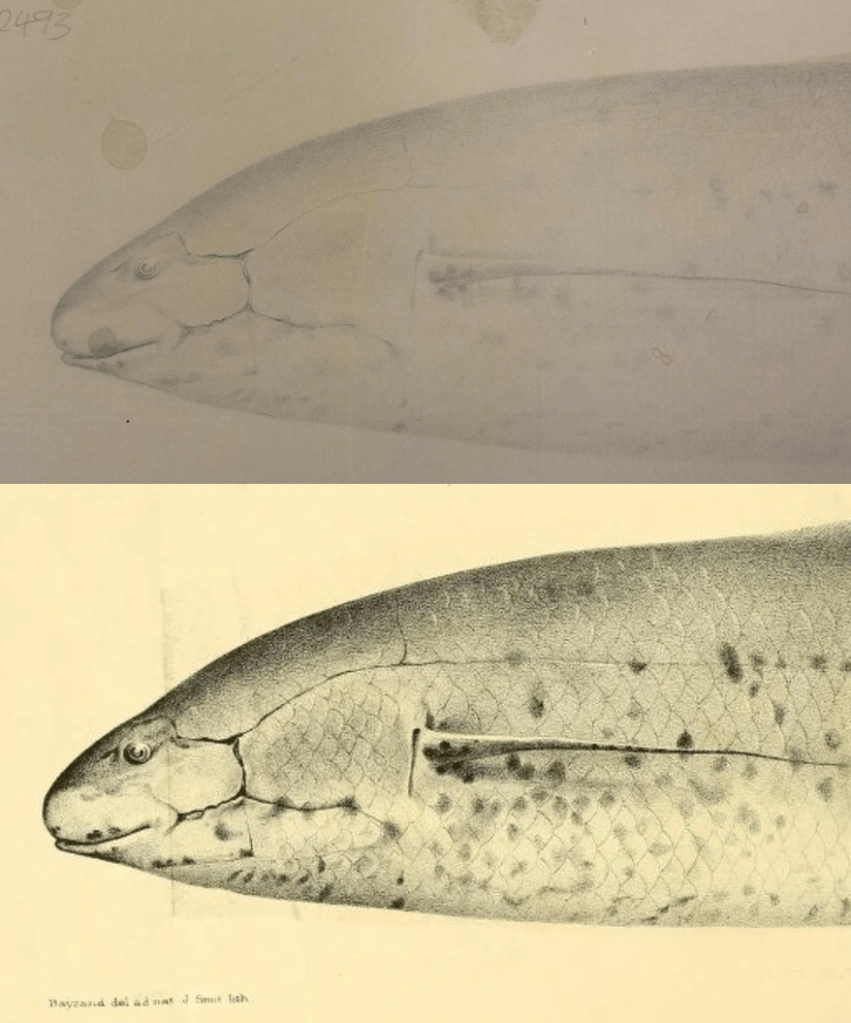

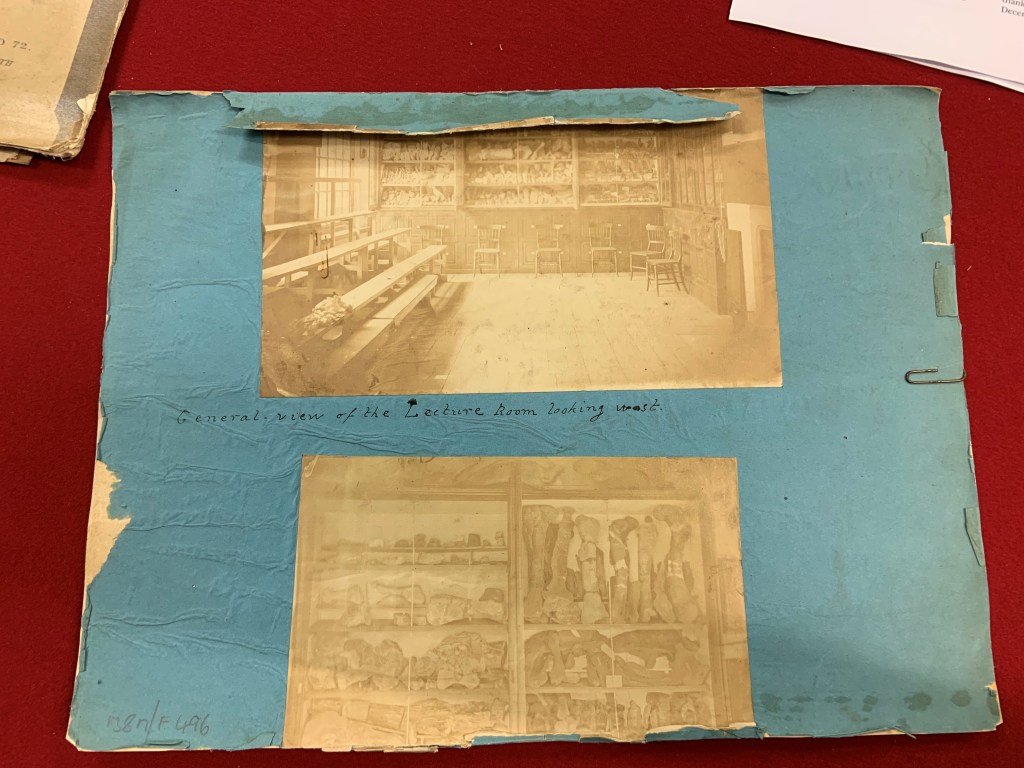

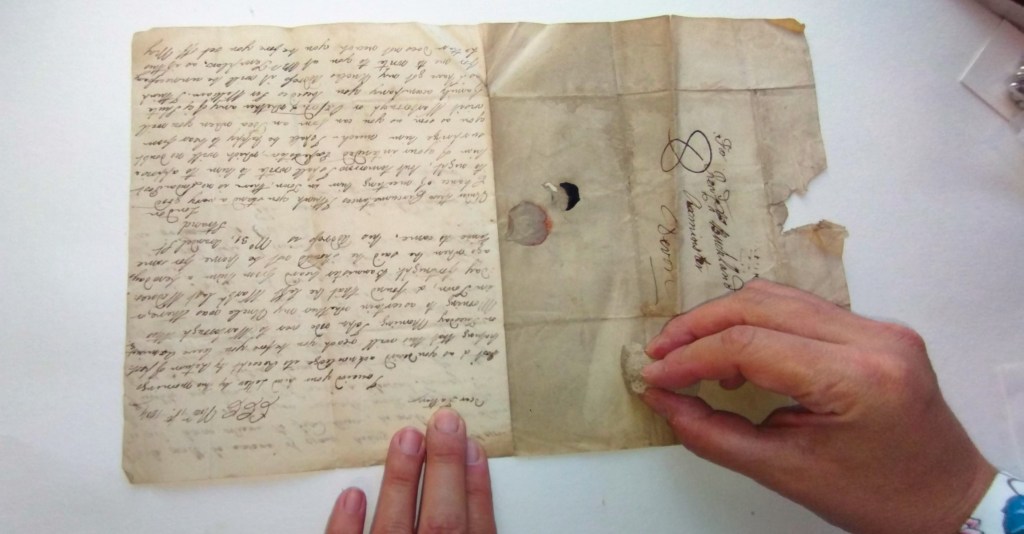

Past efforts had been made to restore the documents, but sometimes these had disfigured the original manuscripts: “in-fills” had been made with unsuitable paper, and backing sheets had been added in bright colours like blue or green. The archive was also being held together with unstable and rusty paper clips, and many of the original wax seals had cracks. It would have been a great shame to lose any of the seals, which feature beautiful examples of natural history icons, like ammonites and cephalopods.

PRESERVING HISTORY

The objective of my work was to stabilise the Buckland archive to ensure its long-term preservation and restore the appearance of the collection so it could be safely handled, digitised and exhibited in future.

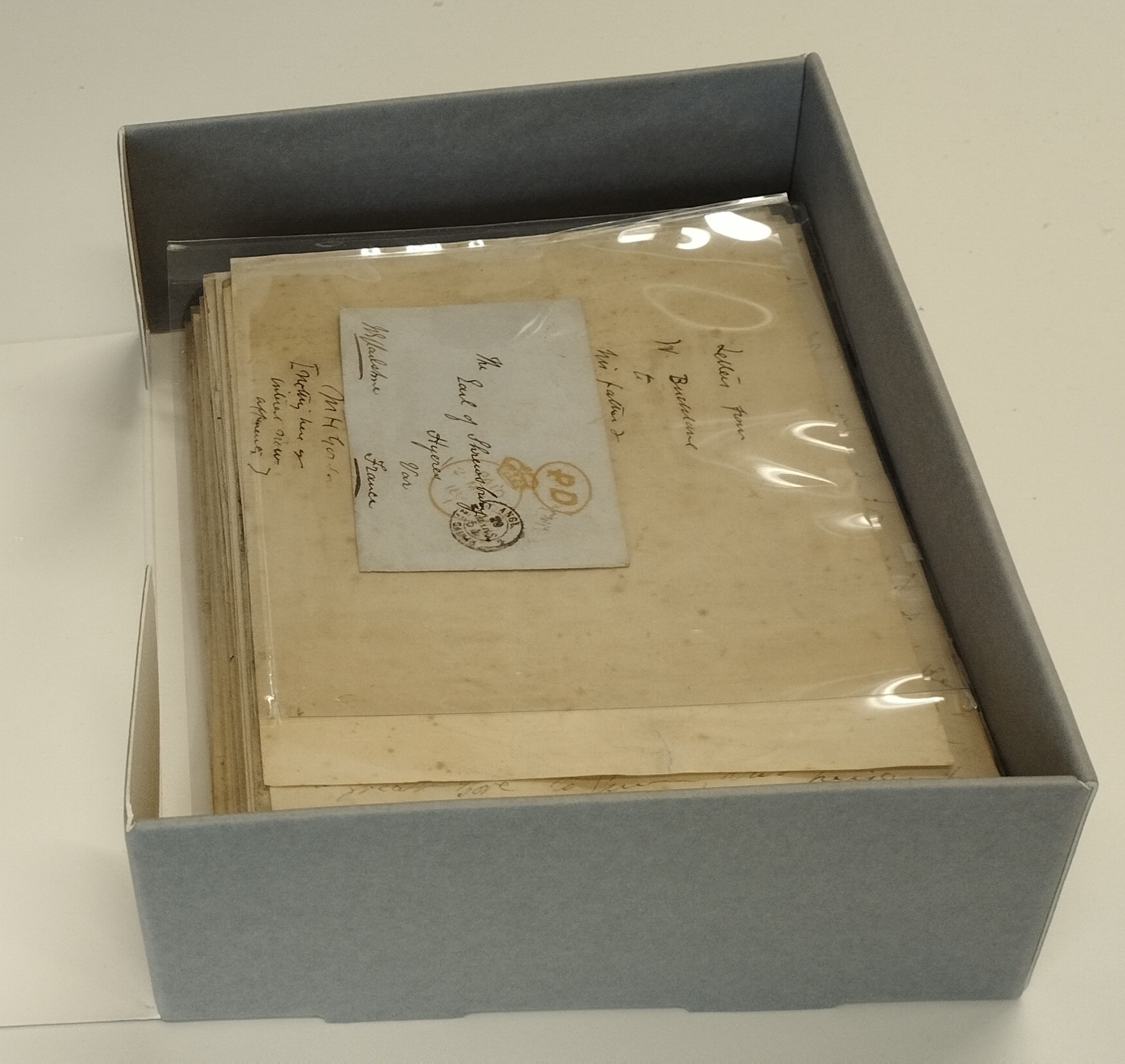

One of the most important principles behind conservation is doing the ‘least amount to do the most good’. Conservation aims to slow down the ageing and deterioration process by using treatments that will not damage or disfigure the integrity of the original document. Conservation may be preventative — for instance, moving documents to a new box that creates the right ‘microclimate’ for their preservation. It may also be interventive — e.g. repairing with non-acidic and reversible materials that can be easily removed at any time, and that also can stand the test of time.

During my time at the Museum, I have been able to conserve a number of the most at-risk and important pieces of archival material. In some cases, this involved a light clean with a soft brush and re-housing of the most overcrowded items. In other cases, I performed more interventive and invasive conservation treatments including mechanical surface cleaning with smoke sponges, relaxing folds with paperweights or steam, stabilising iron-gall inks with gelatin to prevent further corrosion, mending tears with different grades of Japanese papers and tissues, and cleaning and consolidating cracks in the wax seals on the letters to prevent further loss. I also tackled some of the previous ‘repairs’ by eliminating old animal glue which had left the manuscripts shiny in places, carefully removing the unsuitable paper, and adding supports where necessary, thus leaving no traces of the bright blue backing paper.

INTERESTING AND UNEXPECTED STOWAWAYS

As well as undertaking conservation repairs, I also documented the condition of the items; photographing the manuscripts before and after conservation treatments to ensure the Museum, or any other future conservators, have a record of my work. Whilst undertaking conservation treatments, I found some interesting and unexpected stowaways in the archive. What looked to be small holes in one of the pages of a letter ended up being recognised by one of the Museum’s entomologists as spider frass (poop). A moth had also decided to call the papers home at some point in the last two hundred years as I came across a small cocoon that was now long dead, desiccated (dry) and dusty. The most unusual find, however, was a small black dot that I initially thought was an insect. However, employing the help of a microscope and one of the Musuem’s entomologists, we realised that it was actually a seed! What kind of seed, and how or when that seed came to reside in the Buckland archive, we don’t know, but it shows the archive had a life and story of its own long before it came to rest here in the Museum.

A JOB WELL DONE

Overall, I was pleased with the amount of work I was able to accomplish at the Museum. I managed to conserve a significant amount of the archive and was fortunate enough to work with, and learn from, a range of museum staff, including palaeontologists, geologists, zoologists, entomologists and the Life and Earth collections conservators. It has been a privilege to share and exchange knowledge with my colleagues and work collaboratively on the preservation of an important archive. I look forward to hearing about some of the research findings it produces, and to see it shared with the public in future exhibitions and displays.

Thank you to the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust and Helen Roll Charity for funding Anna’s work. Items from the Buckland archive will feature in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition ‘Breaking Ground’ opening 18th October 2024.