For our new exhibition, Bacterial World, we embarked an exciting science/art experiment to make visible the colonies of bacteria present on a wide range of our everyday items and belongings. Once cultured and photographed, eight of these colonies were captured by artist Elin Thomas as a set of crochet artworks that are on display in the exhibition. Our exhibitions officer Kelly Richards tells us more…

For every human cell in your body, a bacterial cell is also present. These bacteria are part of our microbiome, a vast array of microorganisms that use our body as a home and our food as a source of nutrients. In return, the bacteria help us to digest food, maintain our immune systems and keep dangerous bacteria at bay. In fact without these bacteria we would be very sick indeed.

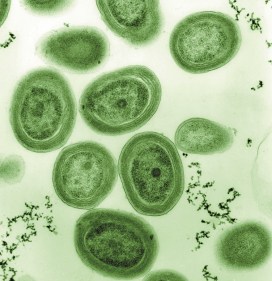

It’s hard to see our microbiome because individual bacteria can easily be as small as 0.2 microns; you could fit over a thousand of these smallest bacteria on one side of a red blood cell. But if we can select and artificially grow the bacteria, their colonies become living, breathing cities visible to the naked eye.

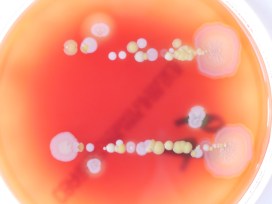

Agar plates contain a semi-solid jelly impregnated with nutrients to fuel bacterial growth. Bacterial cells grow by dividing, and the time taken for each cell to divide and produce two copies of itself is known as the generation time. This can be hugely variable between species, ranging from 20 minutes to over 12 hours, and also depends on growth conditions such as temperature. On this agar plate, we can see distinct bacterial colonies of several different species (all the individual differently shaped and coloured “blobs”), which have come from single (or a very small number of) bacterial cells through this division process over 12-16 hours. How many different types of colony can you see? – Nicole Stoesser

When sampling everyday objects for microbial growth it is inevitable that a mixture of fungi and bacteria, as well as other microorganisms, could grow. That was the case for the majority of the objects printed, with particularly good examples being hair grips and toys. We expected that different objects would be home to different types of bacterial species. Staphylococci (spherical shaped bacteria), for example, are commonly found on skin so we would expect to see them from prints of rings, necklaces and watches. Interestingly, some items resulted in the growth of very little to no bacteria. As bacteria are found pretty much everywhere, the absence of any growth likely indicates the difficulty in growing certain types of bacteria within the laboratory. – Rachael Wilkinson

It is also possible to include dyes, antibiotics and other substances that speed up or slow down the growth of certain types of bacteria to help us select and identify particular bacterial species. This photo, for example, shows a chromogenic agar plate, which contains special dyes that change colour in the presence of substances produced by the bacteria as part of their survival and growth. Pink colonies in this case, for example, contain enzymes that break down lactose, a type of sugar. – Nicole Stoesser

Click the images above to find out more about culturing bacterial colonies

Colonies, both natural and artificial, can contain billions of bacteria as well as the materials that they secrete such as slime, which helps them to move across surfaces, and antibiotics, which kill off other bacterial colonies that could compete for food and space. In their attempts to dominate the space and food available, as well as get enough oxygen to live, colonies can create beautiful, complex structures.

We had a go at visualising the bacteria that live invisibly alongside us by asking visitors to take part in a simple experiment. With the help of microbiologist Rachael Wilkinson, we took items such as coins, keys and jewellery and touched them lightly against agar plates – dishes containing a nutrient-rich jelly that aids bacterial growth. The agar plates were then given to Nicole Stoesser, a clinical microbiologist at the John Radcliffe Hospital, who grew them in the safe environment of the laboratory.

Plastic USB Stick (68) Crochet, by Elin Thomas

Unicorn toy (32) and metal key ring (24) Crochet, by Elin Thomas

Worn sock (25) Crochet, by Elin Thomas

Gold wedding ring (12)

Wood pencil, two sides (64) Crochet, by Elin Thomas

Silver necklace (45) Crochet, by Elin Thomas

Key (71) Crochet, by Elin Thomas

Gold wedding ring (3) Crochet, by Elin Thomas

Many different types of colonies grew from the objects we printed. In the collage above, eight of these colonies have been represented as crocheted Petri dishes by artist Elin Thomas. These artworks are on display in the Bacterial World exhibition until 28 May 2019.

In the gallery below is a photograph of every participant’s plate, whether anything grew in it or not. Click on an image to see a larger version. If you took part in the experiment you will be able to identify your own plate from its number.

The results go to show that we really are living in a bacterial world!