A GUT FULL OF SAND

UNEARTHING THE PECULIAR EATING HABITS OF A TRIASSIC MAYFLY SPECIES

During the summer months, the beaches of Mallorca offer an irresistible draw for tourists and palaeontologists alike. Visitors to the small Spanish island find themselves lured by its glittering seas, captivating coastline, and tasty white sands…

…well, tasty for some, at least!

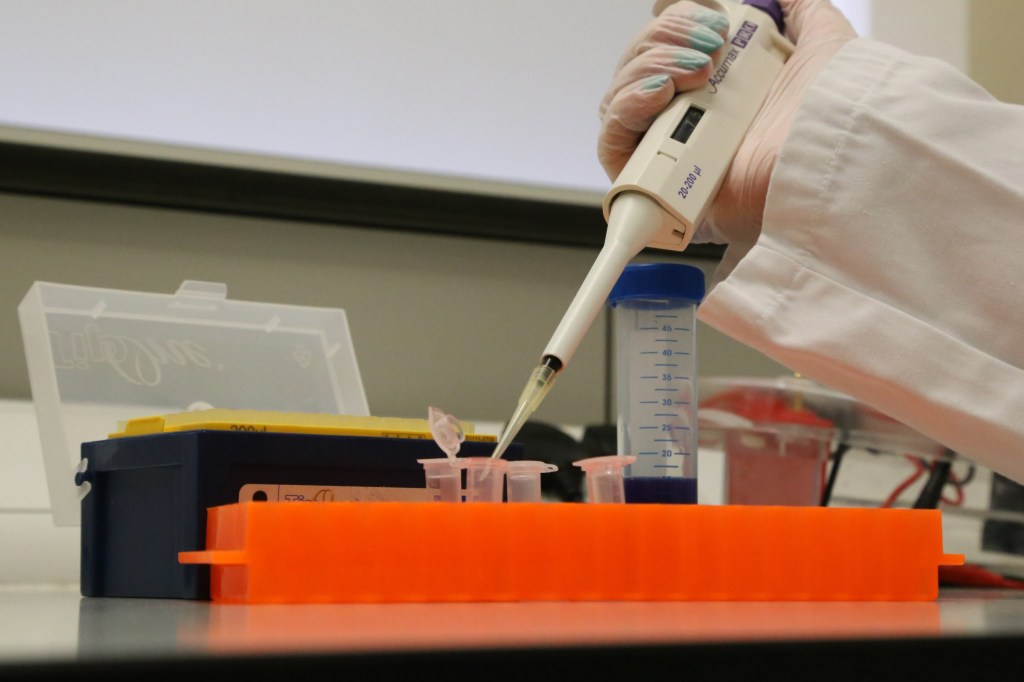

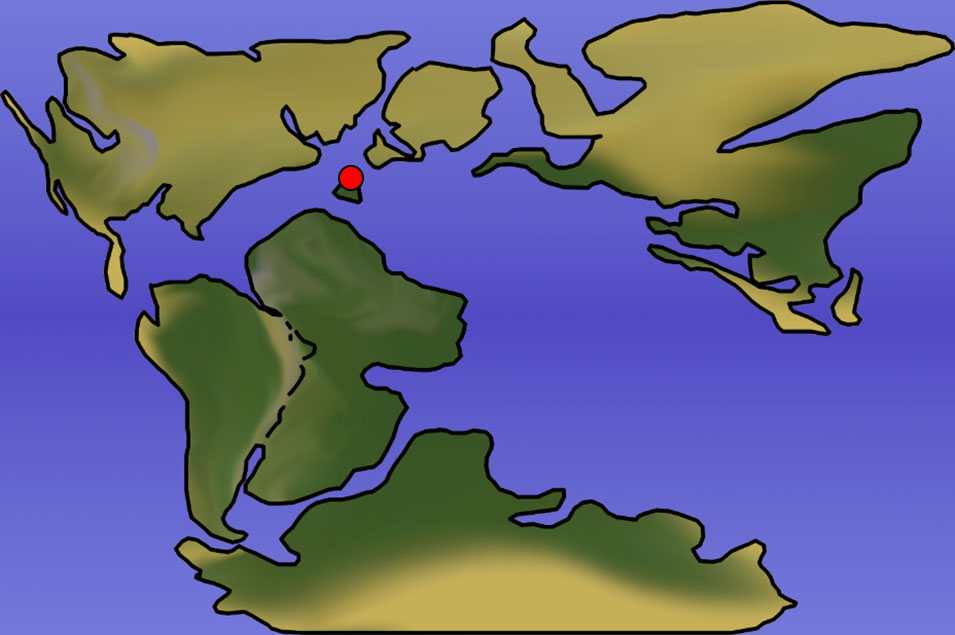

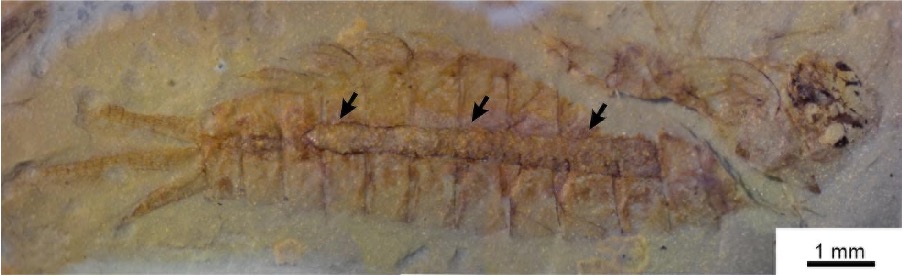

Following recent fossil excavations near the the coastal town of Estellencs in southwest Mallorca, palaeontologists have discovered evidence of a species of mayfly with a pretty peculiar diet. The mayflies in question lived 240 million years ago in bodies of water associated with ancient floodplains. Some of the juvenile mayflies (nymphs) were so well-fossilised that it has been possible to study the contents of their guts. A research team, led by Dr Enrique Peñalver, and featuring OUMNH’s own Dr Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente, discovered that the mayflies’ digestive tracts contained a mixture of detritus (the decomposed remains of other organisms) and particles of a type of rock known as claystone. The most likely explanation for this strange food-pairing? It seems that the nymphs actually survived by eating muddy sediments that had settled to the bottom of the swampy-waters they lived in – yum!

If you’ve ever tried eating a sandwich on the beach, you’ll be familiar with the feeling of sand in your teeth. The sharp crunch of mineral sediment is worth the sacrifice for the delicious, digestible portion of your sandwich – the bread and fillings. Animal digestive systems are unable to extract energy from inorganic mineral matter, like sand. Instead, we rely on organic material for nutrition, i.e. matter derived from plants and other animals. It seems that the Triassic mayfly nymphs found in Mallorca would have munched through large quantities of sediment; digesting the organic detritus it contained, and excreting the inorganic remainder.

Sediment-based diets are extremely rare among living insect species. A handful of modern mayfly species have been observed to munch on the muddy sediment that surrounds the openings of their tunnels, but this is a very rare occurrence. Sediment is a pretty challenging food source, and it’s hard to say why insects may have relied more heavily on it in the ancient past. It is possible that the mayflies found in Mallorca adopted their diet as a result of the Permian mass extinction, which killed off more than 80% of all the species on Earth, ‘just’ five million years prior. With fewer choices of organic material available to eat, perhaps the mayflies were left without a better choice? Or maybe they were simply exploiting new environmental niches that opened up in the aftermath of this catastrophic event?

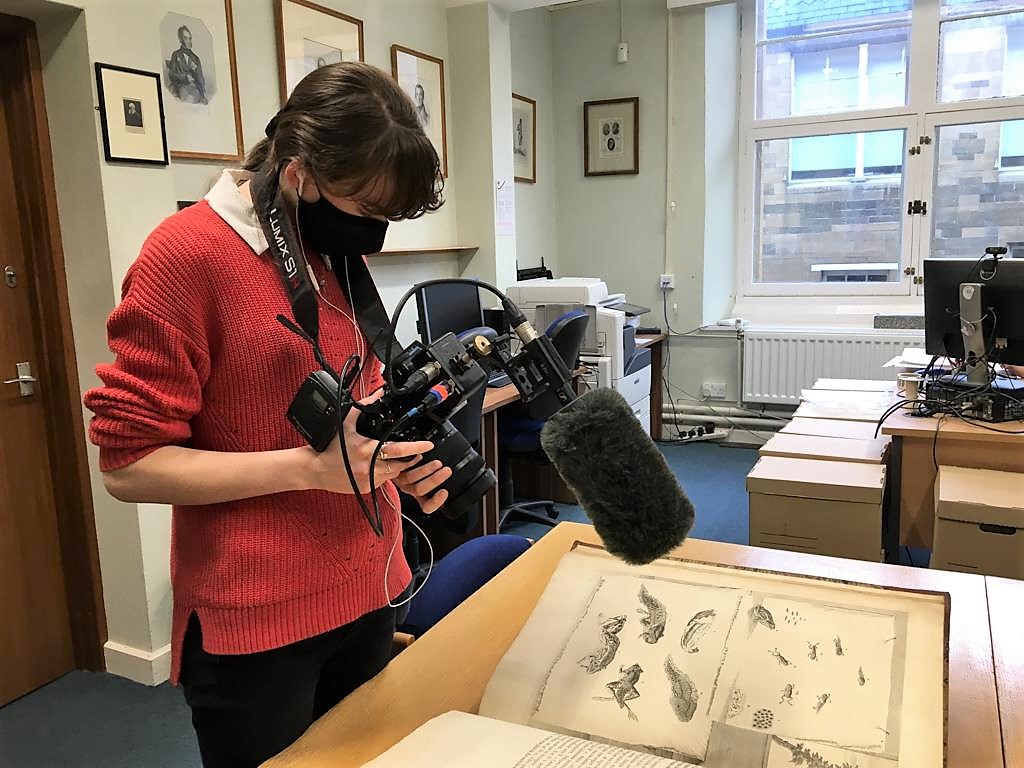

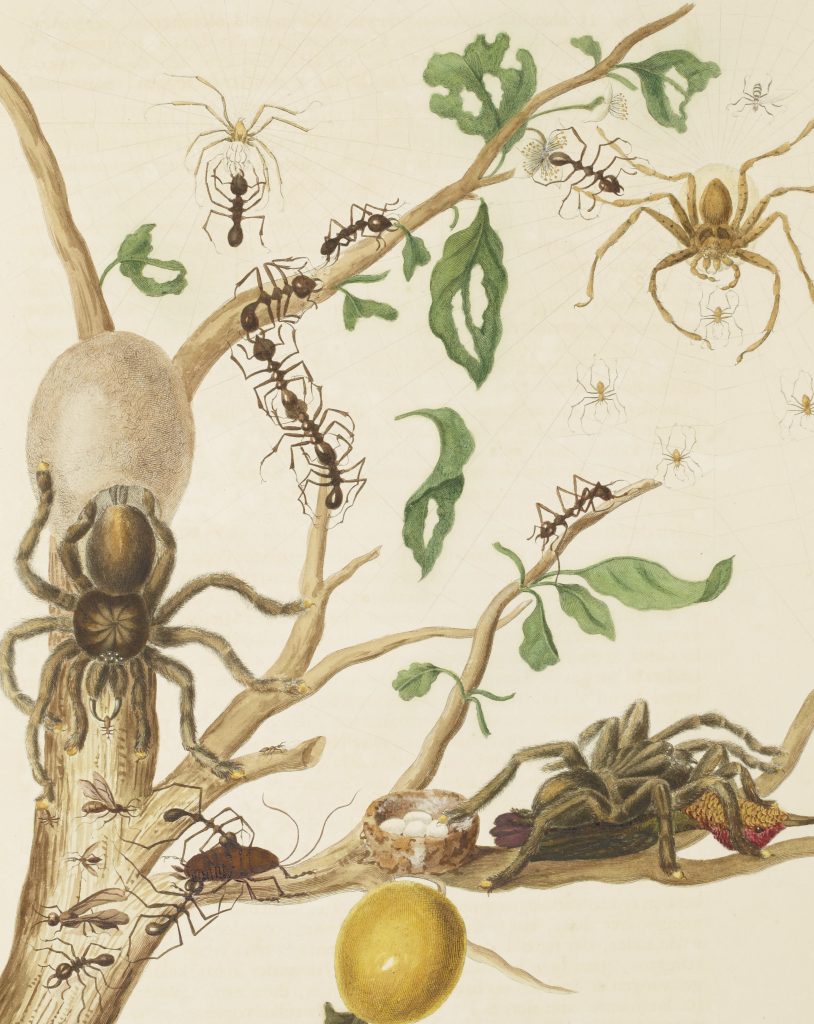

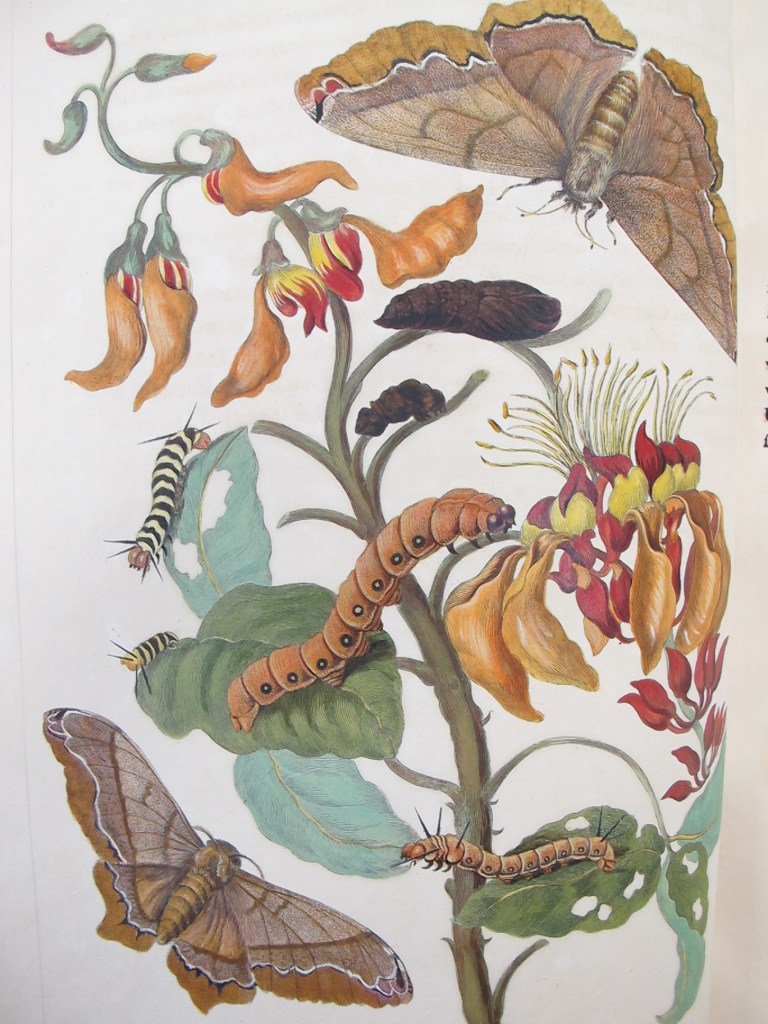

One of the reasons why it is so difficult to theorise about the evolution of species following the Permian mass extinction is the dearth of fossil evidence dating from the period. Luckily, the coastal cliffs of Mallorca can offer us a rare, exciting glimpse into some of the ecosystems that existed ~247 million years ago. The research team behind the Mallorcan mayfly discovery have also used fossils from the same site to describe the world’s oldest-known dipteran (a group of insects including flies, mosquitoes, gnats, and midges), naming the species Protoanisolarva juarezi. These flies would have lived on land, in back swamp areas, rather than in the water. However, much like the Triassic mayfly nymphs, they would have fed on detritus, and played a key role as recyclers of organic matter in these ancient ecosystems.

It is by paying attention to tiny insect fossils like these that we might hope to find answers to one of the biggest questions in palaeontology: how did life rebuild in the aftermath of our planet’s worst mass extinction? And what might this teach us about ecosystem responses to future mass extinction events?

By Ella McKelvey, Web Content and Communications Officer