Museum’s Mary Anning Fossil Gets Stamp of Approval

200 years since OUMNH’s very own Megalosaurus fossils were used in the first scientific description of a dinosaur, the Royal Mail has launched The Age of Dinosaurs, a two-part series of commemorative stamps. The stamps include one series of palaeo-art reconstructions of Mesozoic dinosaurs and reptiles and another series celebrating Mary Anning (1799-1847), a self-taught anatomist and fossil preparator, and one of the most important figures in early geology.

Dr Emma Nicholls and colleagues discuss some of the fascinating stories behind the species and specimens featured on these stamps.

Megalosaurus stamps

Two of the stamps in the Age of Dinosaurs stamp set include artistic reconstructions of Megalosaurus by the palaeo-artist Joshua Dunlop. The animal that nineteenth-century naturalists once understood to be a lumbering long-legged lizard is now depicted as a fearsome Jurassic predator that ran on its hind legs and tore into prey with its large serrated teeth. Dunlop shows Megalosaurus wading through shallow coastal waters, preparing to pounce on Cryptoclidus¸ a plesiosaur that lived alongside Megalosaurus in Jurassic Britain. The artwork also shows Megalosaurus covered in feathers. Although we don’t have any direct evidence that Megalosaurus was a feathered dinosaur, feather-like filaments have been found among the fossils of other dinosaurs such as Sciurumimus, meaning it is highly possible that Megalosaurus had feathers too.

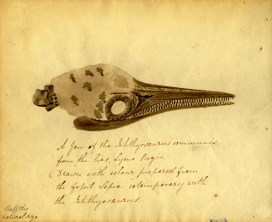

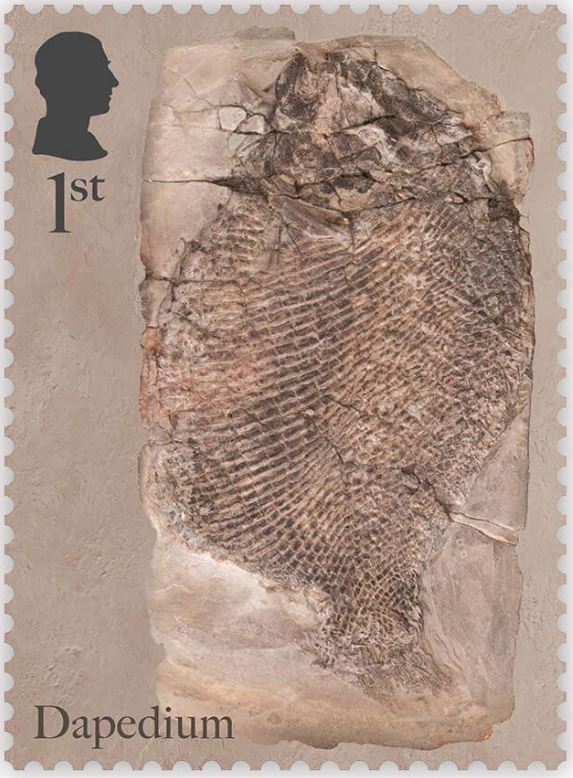

Dapedium stamps

OUMNH collaborated directly with Royal Mail to help produce the Age of Dinosaurs miniature sheet, which showcases fossils collected by Mary Anning. One of the stamps in this collection features a photograph of the fossil of an extinct Jurassic fish, Dapedium, which is housed at OUMNH.

Despite Anning’s illustrious reputation, it wasn’t always known that this Dapedium specimen was connected to her — all that was known about it was that it had probably once belonged to William Buckland and had been collected from Lyme Regis.

Although Anning is one of the most prolific fossil collectors to have worked in Lyme Regis, naturalists like Buckland often visited Anning to go “fossicking” together, or purchase fossils from her. There are very few archival records of transactions between Anning and other fossil collectors from this time, making it difficult to decipher exactly who extracted fossils such as this, found in nineteenth-century Dorset.

Fortuitously, while Dr Sue Newell was conducting research for her PhD on the Buckland Collection in 2021, she found an exciting letter in OUMNH Archive, dated 3rd September 1829. It was from a former student of Buckland’s, Beriah Botfield, and contained details of two fossils that Buckland had bought from Anning to present to the University of Oxford. Using evidence in the letter, Sue was able to work out that Botfield was referring to a Dapedium fossil which she later recognised tucked away in OUMNH’s fossil store.

Botfield had had the fossil mounted in an expensive (and very heavy!) stone frame, with “Presented by Beriah Botfield Esq. Dapedium politum. Lyme, Dorset” beautifully inscribed on the front surface. At the time, the identity of Anning as the fossil’s original finder, identifier, preparator and vendor, was probably common knowledge and, typically, Botfield did not consider these facts important enough to record on his presentation frame.

The Dapedium fossil is a near-complete example of this Jurassic fish, in which scale patterns and delicate fin structures are preserved in breathtaking detail. Dapedium is the first OUMNH object to grace a Royal Mail stamp – an ideal choice given its scientific and historic importance.

Visit the Museum to see the Dapedium fossil as well as temporary displays about the new stamp collection.

Find out more about our special programme of events, exhibitions, and activities honouring Megalosaurus in 2024: The Oxford Dinosaur That Started It All.