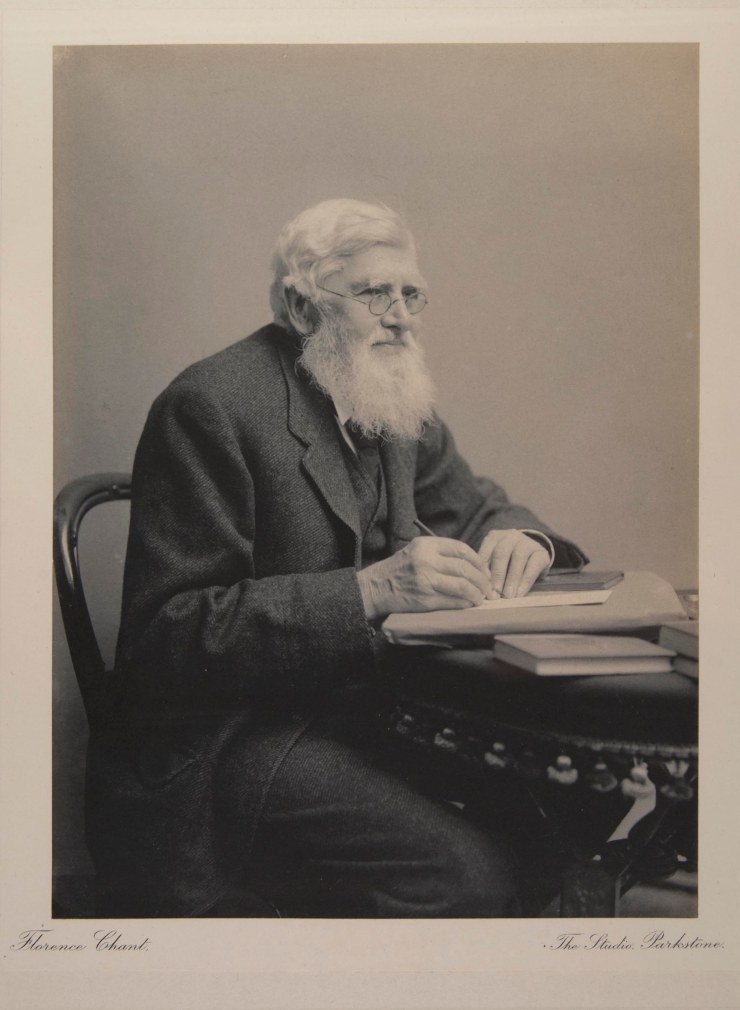

This Thursday, 7th November, marks 100 years since the death of the famous Victorian naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace. Wallace was an intrepid explorer and prolific collector and is hugely important in our understanding of the natural world. He co-discovered evolution by natural selection with Charles Darwin and we are fortunate to have several hundred of his specimens and letters in our collections here at the Museum of Natural History.

To celebrate the life of such an important scientific figure, we’re dedicating this week on the blog to all things Wallace. We’ll be sharing some hidden gems, little known facts about the great man and stories of Museum staff walking in the footsteps of Wallace.

So here begins Wallace Week, with a description of one of his fantastic specimens…

This week’s What’s on the van? comes from Sally-Ann Spence of Minibeast Mayhem and the Bug Club.

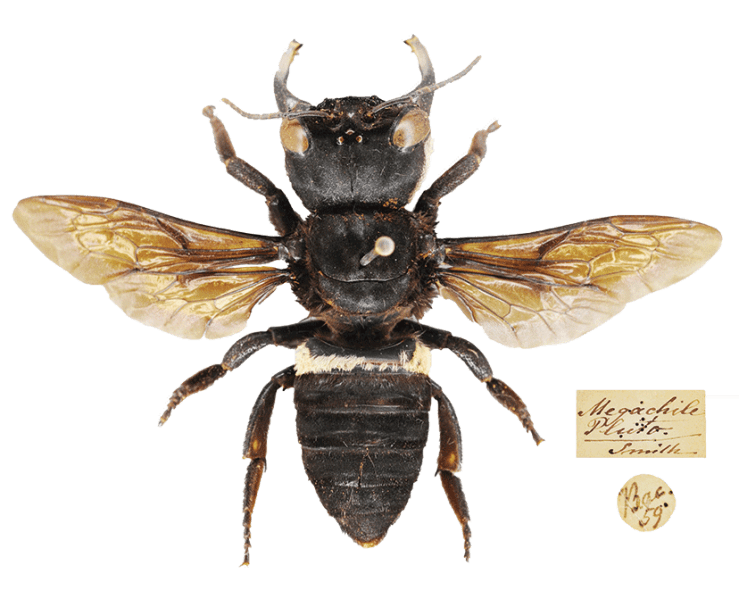

A single female bee stands out dramatically from all the bees in Oxford University Museum of Natural History’s bee collection and not for one reason, but three.

Firstly and quite simply is her impressive size. With a 63mm (2.5”) wingspan she completely dwarfs all her companions. Secondly, she has the most enormous and impressive mouthparts: jaws longer than her actual head held agape in the same fashion as a stag beetle’s mandibles.

The third reason and perhaps the most special, is not associated directly with her body, but the little unobtrusive label impaled with her on the pin. Alfred Russel Wallace was inordinately fond of using tiny round paper discs to store information on when mounting his specimens and this bee is in fact called Wallace’s Giant Bee, Megachile [Chalicodoma] pluto, the world’s biggest bee. It was first discovered by Wallace in Indonesia in 1858 and then thought to be extinct until 1981, when it was rediscovered by the American entomologist Adam C. Messer.

It really is the most interesting and unusual bee. The females are not only larger than the males in general size but also have the markedly more impressive mouthparts. They appear to use these jaws to collect resin from trees by rolling it up into neat balls for transport in flight. Then they mix it with wood and dried fibres to make a waterproof nesting material.

The next amazing thing is where they actually build their communal nests. Not underground or in cavities, but inside the already existing nests of tree-dwelling termites. Surprisingly, very little is known about the world’s biggest bee. It may be nesting within the termite colony to ensure a microclimate for its own young. It may be gaining protection from predators and parasites by being there. Perhaps it is a combination of these reasons.

It is possible that when Wallace collected this specimen in 1858 he was completely unaware of its nesting behaviour, so it then remained hidden for so long within its termite cloak. Even the local people were unaware of its very existence, although local folklore was based upon it.

This lone female bee and her famous collector are a constant reminder to us all today why research is so vital and of the huge importance of museum collections.

Reblogged this on Dorset County Museum.

Interesting! Though it looks like the label says Smith not Wallace, or am I mistaken?

Hi Sam – good spot! Yes, the rectangular label says Smith, because Frederick Smith described it for science, even though Wallace discovered it. It’s the circular label that belonged to Wallace and bears an abbreviation of the location where he found it- Bac for Bacan Islands in Indonesia.

[…] ← Previous […]

Really interesting post. I’ll have to look up how the bees deal with the termite colony defenses. Chemical mimicry? Odd.

The proper citation of the scientific name of Wallace’s Giant Mason Bee is Megachile (Chalicodoma) pluto, not Chalicodoma (Megachile) pluto. The handwriting on the disc label is that of Wallace’s field assistant Charles Allen.

Thanks Chris. Will amend the text.

[…] Wallace’s Giant Bee […]