By Rachel Parle, Education and Interpretation Officer

Dinosaurs were living, breathing, moving animals, but that’s sometimes hard to visualise when standing in front of a skeleton. We may not be able to reincarnate dinosaurs in the style of Jurassic World, but an excellent illustration of the animals in their environment can go a long way to bringing them back to life.

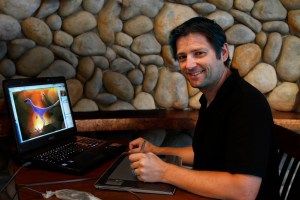

When Earth Collections Manager Hilary Ketchum and I set out to update the labels for our free-standing dinosaur skeletons, we wanted to present current science alongside scientifically accurate illustrations. They should be beautiful and show the dinosaurs as dynamic animals. We found just the person for the job. Julius Csotonyi is a paleoartist, wildlife artist and scientific illustrator who specialises in life-like restorations of prehistoric animals and habitats. He understood exactly what we wanted and set to work researching featured specimens.

After several rounds of checks and suggestions from scientists in the Museum and the University, the illustrations are all complete and the new labels are on display in the Museum. So I asked Julius a few questions about his work and how he felt having completed the project.

**

How do you ensure your representations of dinosaurs are accurate?

Ultimately, all of my reference material comes from palaeontologists’ research. For all reconstructions, I rely heavily on published scientific literature. For reconstructions of newly discovered taxa, of which I am commissioned to do quite a few for press releases and scientific papers, I also have discussions with the palaeontologists who have made the discoveries, since the material is not yet published. This latter process is some of the most exciting, because I am able to participate in the process of scientific discovery, keeping a foot in both camps of science and art.

How important do you think the dinosaur’s environment is in the representation?

The environmental context provides the opportunity to tell a more detailed story of the animal’s role in the biological community, its position in the food web, or interesting aspects of its behaviour. Depicting the animal’s environment provides me the opportunity to employ creative and interesting lighting conditions and composition to generate an image that is as aesthetically appealing as possible – this is art, after all, and I feel it’s important to make it as beautiful as I can.

How did you become a paleoartist and what do you enjoy about it?

I absolutely love my job. It’s wonderful to play a part in piecing together and visualizing worlds that are millions of times older than I am. It was during the completion of my PhD in the microbiology of extreme environments that my work in scientific illustration and paleoart really took off, when I was first contacted to help illustrate a book about dinosaurs by author Dougal Dixon. Ultimately I realized that scientific illustration provided me with a more consistent enjoyment, so I made scientific artwork my full time work as soon as I completed my degree. I know that I am in the right field of work because even when I am juggling projects under the extreme pressure of impending deadlines, I still find great enjoyment in the act of painting.

How do you feel about your work being on permanent display here?

I feel greatly honoured to have my illustrations incorporated into a permanent display in this renowned and respected institution. It is my hope that my work will help in a small way to interest the public in the intriguing field of palaeontology, and this excites me, for I feel strongly about contributing to scientific outreach. Many thanks to the museum team for allowing me to participate!

**

Next time you call by the Museum, stand in front of a dinosaur, have a good look at its new label and see if it comes to life before your eyes.

Rachel Parle, Interpretation and Education Officer

All images are copyright Oxford University Museum of Natural History and Julius Csotonyi.

No keratin on the Triceratops frill? Why is no one doing this? Brilliant work though, love the art.

Ooh, interesting debate -will ask Julius! Glad you like the illustrations – we think they’re great too. Rachel

Thanks! That’s an interesting question. I’ve approached paleontologists about the integumentary covering of ceratopsians’ frills, and one of the things that keeps popping up is that there appears to be a paucity of integumentary material from their frills, aside from evidence of heavily keratinized scales and pads in Pachyrhinosaurus. Of course, it’s possible I’ve missed something, and am always interested in new material, but I know of no skin impressions of Triceratops frills.

Thanks for the informative response, Julius. R

A pleasure!

Wonderful and accurate ilustrations! I appreciate how you paid close attention to T. rex’s lips, how you made the upper lips longer as very long lower lips would not be able to accomodate the teeth alone because they would fall a little bit to the sides due to their lenght (T. rex’s tooth crowns were very long in proportion to the mouth). Well done!

I only want to say that I find such lips unlikely because such lips would probably caught the attention of rivals sometimes (look at this: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HD8AIl… the lips really caught our attentions a bit), and as T. rex had very long tooth crowns in proportion to the overhaul jaw (so what i will say does not apply to most theropods), the rivals would most likely try to bite the lips off sometimes (even if this behavior was rare, it would constantly fight and it would be very likely for a rival to try to bite off the lips of another T. rex at least once) and we would find long, clear tooth marks (like these blog.everythingdinosaur.co.uk/…) on some parts of the dentaries of some specimens (and maybe on the maxilla, but as long lips there would not be so… obvious, I think uit would be kinda difficult), something that does not happen.