A poetic ending

Steven Matthews, one of our three Poets in Residence, reflects on his residency at the Museum during our Visions of Nature year.

It is sad that our poetry residency is at an end; I shall miss the frequent escapes for the hustle of the everyday Oxford streets into the light and space of the Museum.

As a resident in Oxford for over twenty years, I had gradually accumulated a bit of knowledge about the building. I had, like so many local parents, hugely enjoyed taking our two sons there when they were young, and loved to see their delight at the displays. Seeing the fossil, mineral, and animal world, as it were, through their eyes, really re-engaged me with its wonders.

I have been very privileged, then, to go ‘behind the scenes’ at the Museum, and to speak to the scientists engaged in research into its collections and history. They are bringing new knowledge and understanding to bear at a moment when, let’s face it, humankind has inflicted catastrophe upon the natural world, and so upon itself.

The Victorian spirit and vision which instigated the building of the Museum, a spirit revelling in creation and in exorbitant creativity, seems very remote. This is tragically borne home when looking at the cabinets of butterflies and moths, the Lepidoptera, where the majority of the specimens are of species that no longer exist.

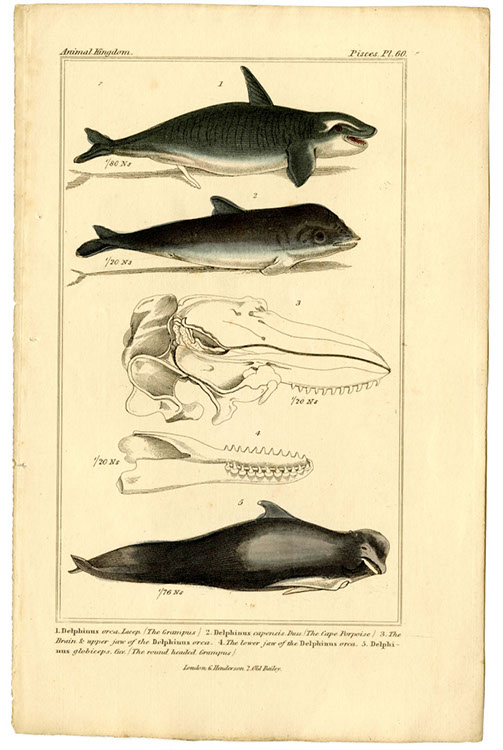

The prime mover behind the Museum, the Victorian Henry Acland, said in an early promotional lecture that the ambition behind it was to show that all branches of science needed to work together to produce a greater understanding of the world. The zoologist could not understand the physiological structure of animals without deploying information and knowledge held in common with the geologist and the anatomist.

The Museum should be a place where that type inspiring dialogue could occur daily. It feels as though we are in a moment now where that collaboration, and collective and imaginative ingenuity, is hard-pushed to find solutions to the divided interests and dire afflictions of the world.

The Visions of Nature year at the Museum, which brought artists and us poets together with the scientists, has been one way in which all of these things have been, for me excitingly, furthered. It has been a challenge and a thrill to imagine and write – ‘in their own voices’ – lives for some of the Museum’s specimens which have particularly fascinated or moved me. But also a great delight, for which I’ll always be grateful.