At home in Yorkshire

In rush hour traffic, carrying a precious cargo, the Museum’s Director, Professor Paul Smith and Head of Archival Collections, Kate Santry, headed north. They took the William Smith archive on tour to the Yorkshire Fossil Festival, in lovely Scarborough. Hosted by the Scarborough Museums Trust, in partnership with the Paleontological Association, the Yorkshire Fossil Festival had a wide array of exhibitors, lectures and events all celebrating fossils over the course of three days.

In rush hour traffic, carrying a precious cargo, the Museum’s Director, Professor Paul Smith and Head of Archival Collections, Kate Santry, headed north. They took the William Smith archive on tour to the Yorkshire Fossil Festival, in lovely Scarborough. Hosted by the Scarborough Museums Trust, in partnership with the Paleontological Association, the Yorkshire Fossil Festival had a wide array of exhibitors, lectures and events all celebrating fossils over the course of three days.

Despite some chilly and cloudy weather the festival saw a great turn-out. On Friday 12th September, a number of local primary and secondary schools made a visit, participating in activities that gave hands-on experience in understanding more about fossils. The school groups who visited our stall had the opportunity to act out a play exploring how fossils are made with our Director, Paul Smith, as the narrator!

The crowds visiting the festival over Saturday and Sunday got a rare look at original material from the William Smith archive and were asked to help us transcribe the collection, which has recently been digitised and catalogued. Although he is ‘the father of English geology’, William Smith is not a universally known figure in the history of science. But it was a very different matter with the Scarborough crowd.

Born here in Oxfordshire, Smith lived in Scarborough at the time he died in 1839 and was an active and important figure in the town. In addition to being an early member of the Philosophical Society, he was also consulted to solve the town’s water supply issues, select stone for the bridge between the town and its newly discovered spa, and most notably in helping to design the Rotunda Museum that was our base for the three days.

The biggest hit at our table over the weekend was the Geological Map of Yorkshire, published by Smith and Cary in 1820 as part of his County Map series. While approximately 400 people spent time looking closely at, and talking with us about this important map, its popularity was followed closely by a copy of Smith’s wine merchant’s bill from Scarborough dated 1839. It certainly appears that Smith was a fan of gin and marsala…

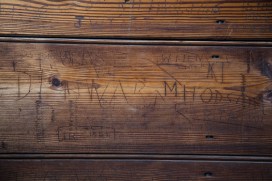

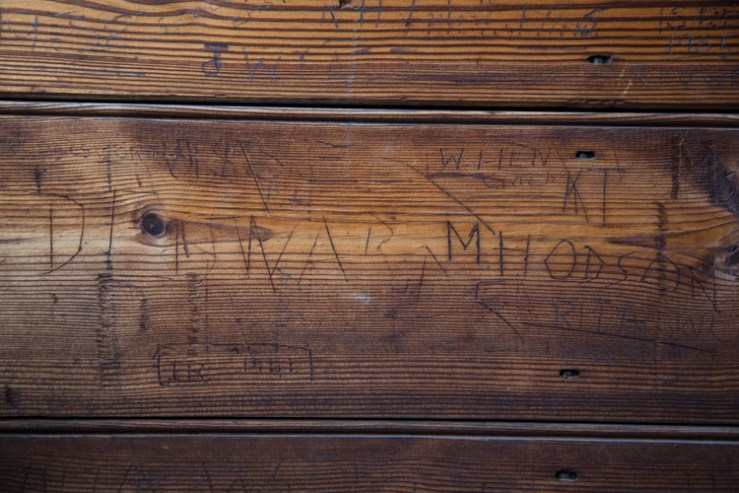

This little room behind the scenes in the museum is entirely wood panelled and seems to have become a spot to make your mark. Covering the walls, the door and even the ceiling are names and dates scratched into or scribbled onto the wood. The dates go as far back as 1920. Names, initials and numbers from the last 10 decades now overlap to create a textured collage.

This little room behind the scenes in the museum is entirely wood panelled and seems to have become a spot to make your mark. Covering the walls, the door and even the ceiling are names and dates scratched into or scribbled onto the wood. The dates go as far back as 1920. Names, initials and numbers from the last 10 decades now overlap to create a textured collage.