How we got bigger, more vulnerable brains

This article is taken from European research magazine Horizon as part of our partnership to share natural environment science stories with readers of More than a Dodo. For more on the development of the brain see our Brain Diaries exhibition site.

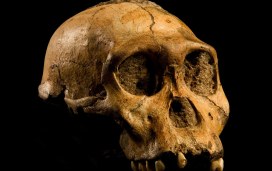

One of the major features that distinguishes humans from other primates is the size of our brains, which underwent rapid evolution from about two to three million years ago in a group of our ancestors in Africa called the Australopithecines. During this period, the human brain grew almost three-fold to reach its current size. Scientists know this from skull remains, but have puzzled over how it happened…

This year, the mystery was partially solved by Professor Pierre Vanderhaeghen at the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology in Belgium. Prof. Vanderhaeghen, who was conducting his work as part of the GENDEVOCORTEX project, went on a hunt for the genes that drove the growth of human brains.

Scientists had suspected that brain expansion began in our human ancestors when they evolved genes that are switched on in the foetus, when a lot of key brain development occurs. Prof. Vanderhaeghen therefore looked for genes present in human foetal tissue, but missing from our closest living relatives, apes.

His lab discovered 35 hominid – present only in apes and humans – genes that were active in foetal brain tissue. They then became intrigued by three specific genes – all similar to NOTCH genes, an ancient gene family involved in sending messages between cells and that are present in all animals. They found that the three new genes, collectively named NOTCH 2NL, were created by a “copy and paste error” of an original NOTCH gene.

This error created entirely new proteins which likely helped our ancestors’ cerebral cortex to balloon. This is the part of our brain responsible for our language, imagination and problem-solving abilities. Scientists at the University of California, Santa Cruz, have also identified the NOTCH 2NL genes in DNA from Homo sapiens’ extinct cousins – the Neanderthals and Denisovans.

(The NOTCH 2NL) genes are only present in humans today. They were also present in Neanderthal DNA, but not in chimpanzees

Prof. Vanderhaeghen

Evolution

These genes control the growth rate and differentiation of brain stem cells – the starter cells that multiply and give rise to all neurons in our brain – causing them to seed more nerve cells, which in turn helped to expand brain size. The genes likely led to more neurons and brain tissue in our ancestor’s descendants – including Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans.

Prof. Vanderhaeghen’s research could also help to provide new insights into brain disorders. The US researchers linked genetic faults in DNA that were very similar to NOTCH 2NL, to children born with enlarged brains or small brains. Many of the new human-specific genes are located in a small area of our genome that plays an important role in brain size, according to Prof. Vanderhaeghen.

As DNA in this area closely resembles another part of the genome where it was originally cut and pasted from millions of years ago, errors are more likely, said Prof. Vanderhaeghen. “Patients who have (inherited) deletions in this area tend to be at risk of developing schizophrenia, whereas patients with duplications are more at risk of autistic spectrum disorder,” he said.

Prof. Vanderhaeghen is now studying some 20 of the remaining human-only genes to see how they contributed to the evolution of the human brain.

Something like 40-50% of the Neanderthal genome can still be found in people today.

Prof. Svante Pääbo, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany

In the last decade, however, scientists have begun to look at the DNA inside these bones. Professor Svante Pääbo, director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, has led the way in sequencing DNA of these extinct humans from small bone fragments.

This allows scientists to compare modern human DNA with that of extinct humans, rather than just living relatives like chimps. Already, the work has revealed some surprising findings – our own species appears to have interbred with some of these ancient relatives during our history.

Ancient humans

Scientists have found that the DNA of every person outside Africa is 1-2% Neanderthal, meaning that these extinct human relatives had offspring with our own ancestors.

“Different people tend to carry different pieces of the Neanderthal genome,” said Prof. Pääbo, who is undertaking a project called 100 Archaic Genomes to decipher the DNA of ancient human individuals. “Something like 40-50% of the Neanderthal genome can still be found in people today,” he said.

According to Prof. Pääbo, we retained some of this DNA because it offered an advantage to our ancestors. “Some (of this retained DNA) has to do with the immune system, presumably helping us to fight off infectious diseases.”

The power of genetics to unravel the history of human evolution took a new twist in 2010 after Prof. Pääbo’s lab sequenced DNA from a finger bone fragment found by a Russian archaeological team in a remote Siberian cave.

The analysis revealed the bone belonged to a previously unknown human relative, now called Denisovans after Denisova Cave where the bone was found. This mysterious ancient human species lived at around the same time as Neanderthals, but further east into Asia.

Last year, Prof. Pääbo’s group published DNA sequences from a tooth found in the cave – the fourth ever Denisovan discovered. We now know Denisovan DNA carries more variation than Neanderthal DNA, leading scientists to conclude that they were more widespread than the better-known Neanderthals.

Denisovans left a more impressive stamp on some of us than Neanderthals, according to Prof Pääbo. Their DNA can be found in people across Asia today, while indigenous peoples of Papua New Guinea and Australia may carry up to 5%. Tibetans also carry some Denisovan DNA in their genomes, which has helped them adapt to life at high altitudes where there is little oxygen in the atmosphere.

Prof. Pääbo and his colleagues will soon publish their third high-quality genome – where almost the entire DNA sequence is intact – of a Neanderthal from Siberia. A deciphered genome of this quality allows for better DNA comparisons and could tell us more about the evolution of important genes – such as those linked to the development and function of the brain. It will add yet another puzzle piece to help us understand the history of our closest extinct relatives, according to Prof. Pääbo.

“There may even be other forms of extinct humans out there to be discovered by studying the DNA of the (ancient) bones we find,” he said.

Top image: The skull of a Australopithecus sediba, a species of Australopithecines, who were our ancestors and whose brains started to grow two to three million years ago. Image credit – Australopithecus sediba by Brett Eloff, courtesy Profberger and Wits University is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

*

This post Genetic error led humans to evolve bigger, but more vulnerable, brains was originally published on Horizon: the EU Research & Innovation magazine | European Commission.