‘A thoroughly unhousewifely skill’

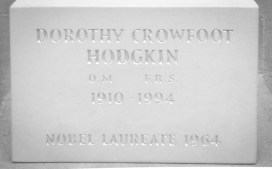

For International Women’s Day, the Museum of Natural History celebrates the life and career of Dorothy Hodgkin, one of its most eminent researchers. Hodgkin was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1964, and is still the only UK woman to have been awarded one of the science Nobels.

When the Museum of Natural History was designed in the 1850s, the building was intended not just to house a museum but also the burgeoning science departments of the University. The lettering above the doors facing the court continues to record these early affiliations: ‘Department of Medicine’, ‘Professor of Experimental Philosophy’, and so on.

As individual departments grew they moved into their own buildings across the science campus. One of the last research groups left in the Museum was the Department of Mineralogy & Crystallography, which, from the 1930s onwards, was the research home of the outstanding X-ray crystallographer Dorothy Hodgkin (1910-1994), winner of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1964.

The Daily Mail famously celebrated her success with the headline ‘Oxford housewife wins Nobel’, but The Observer was no more enlightened, commenting that Hodgkin was ‘an affable looking housewife’ who had been awarded the Nobel Prize for ‘a thoroughly unhousewifely skill’. That socially disruptive ability was an unparalleled proficiency with X-ray analysis, particularly in the elucidation of the structure of biological molecules.

Hodgkin undertook her first degree at Oxford from 1928 to 1932, initially combining chemistry and archaeology but later focusing on the emerging technique of X-ray crystallography. Her undergraduate research project was carried out using this technique in a Museum laboratory within what is now the Huxley Room, the scene of the 1860 Great Debate on evolution between Bishop Wilberforce and T. H. Huxley. She then journeyed across to Cambridge for her PhD before returning to Oxford in 1934 and resuming her association with the Museum.

Back in Oxford, Hodgkin started fundraising for X-ray apparatus to explore the molecular structure of biologically interesting molecules. One of the first to attract her attention was insulin, the structure of which took over 30 years to resolve – a project timescale unlikely to appeal to modern research funders. Other molecules proved more tractable, including the newly discovered penicillin, which Hodgkin began to work on during the Second World War, and vitamin B12. It was for the determination of these structures that she was awarded the Nobel Prize.

Dorothy Hodgkin’s new X-ray laboratory was set up in a semi-basement room in the north-west corner of the Museum. The room is now a vertebrate store but was once also the research home of Prince Fumihito of Japan, when he was based in the Museum for his ichthyological research (and It is still the only room in the Museum with bulletproof windows).

Initially, Hodgkin’s only office space consisted of a table in this room and a small mezzanine gallery above, which housed her microscopes for specimen preparation. Once prepared, she then had to descend a steep, rail-less ladder holding the delicate sample to the X-ray equipment below. Later, Hodgkin had a desk in the ‘calculating room’ (now housing the public engagement team) where three researchers and all of their students sat and undertook by hand the complex mathematics necessary after each analysis to determine the crystal structures of organic molecules.

Paul Smith – Director

If you would like to learn more about Dorothy Hodgkin and her work, then read Georgina Ferry’s excellent biography ‘Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life’ which has just been re-issued as an e-book and new, print-on-demand paperback by Bloomsbury Reader.

This year’s Dorothy Hodgkin Memorial Lecture will be held in the Museum at 5 pm on Thursday 12 March, and is open to all. The lecture will be given by Dr Petra Fromme (Arizona State University) who is an international authority on the structure of membrane proteins.

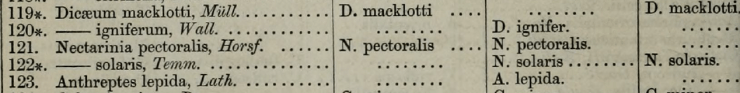

Working on the Lepidoptera Project in the Entomology department keeps me very busy during the day, but I rarely get to see other parts of the Life Collections. So it was a real treat when my boss Darren said I could look at the specimens in the bird skin store. While carefully going through the drawers, I found this spectacular little bird from the family Nectariniidae. The species is Cinnyris solaris, which is also has the evocative name of Flame-Breasted Sun Bird. This particular specimen was an amazing surprise, because of the label data. It states:

Working on the Lepidoptera Project in the Entomology department keeps me very busy during the day, but I rarely get to see other parts of the Life Collections. So it was a real treat when my boss Darren said I could look at the specimens in the bird skin store. While carefully going through the drawers, I found this spectacular little bird from the family Nectariniidae. The species is Cinnyris solaris, which is also has the evocative name of Flame-Breasted Sun Bird. This particular specimen was an amazing surprise, because of the label data. It states:

In 1893, the major portion of the collection was donated to the British Museum in London via a relative, Miss Pascoe, but she donated the remainder to the Hope Department here at the Museum in 1909. Alfred Russel Wallace himself was said to have suggested this. These items were mostly insects, but also included this beautiful Flame-Breasted Sun Bird. Today the Flame-Breasted Sun Bird is a scarce species due to its limited island range, but is not considered threatened. I feel privileged to have chanced across such an amazing specimen in the bird stores. Gina Allnatt, Curatorial assistant (Lepidoptera) ** Letter used by Gina for research can be seen at

In 1893, the major portion of the collection was donated to the British Museum in London via a relative, Miss Pascoe, but she donated the remainder to the Hope Department here at the Museum in 1909. Alfred Russel Wallace himself was said to have suggested this. These items were mostly insects, but also included this beautiful Flame-Breasted Sun Bird. Today the Flame-Breasted Sun Bird is a scarce species due to its limited island range, but is not considered threatened. I feel privileged to have chanced across such an amazing specimen in the bird stores. Gina Allnatt, Curatorial assistant (Lepidoptera) ** Letter used by Gina for research can be seen at

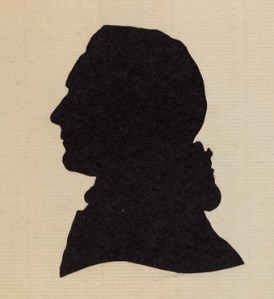

In rush hour traffic, carrying a precious cargo, the Museum’s Director, Professor Paul Smith and Head of Archival Collections, Kate Santry, headed north. They took the William Smith archive on tour to the Yorkshire Fossil Festival, in lovely Scarborough. Hosted by the

In rush hour traffic, carrying a precious cargo, the Museum’s Director, Professor Paul Smith and Head of Archival Collections, Kate Santry, headed north. They took the William Smith archive on tour to the Yorkshire Fossil Festival, in lovely Scarborough. Hosted by the