Oxford team’s fieldwork revealing how complex life first evolved on Earth

By Ross Anderson

In Summer 2024, a team of palaeontologists and geologists from the University of Oxford, along with colleagues from Dartmouth College, the University of Washington, and Williams College in the USA, undertook an expedition to the Little Dal Group in the Mackenzie Mountains, Northwest Territories, Canada. Our purpose was to uncover some of the oldest fossil ecosystems that record complex life.

Photo: Robert Gill

Complex life comprises all organisms whose DNA is enclosed in a cell nucleus. This includes animals and plants but excludes bacteria. Today, this complex life accounts for most of the Earth’s biomass, documented biodiversity, and oxygen production. Understanding when and how it first evolved remains one of the central unanswered questions in evolutionary biology.

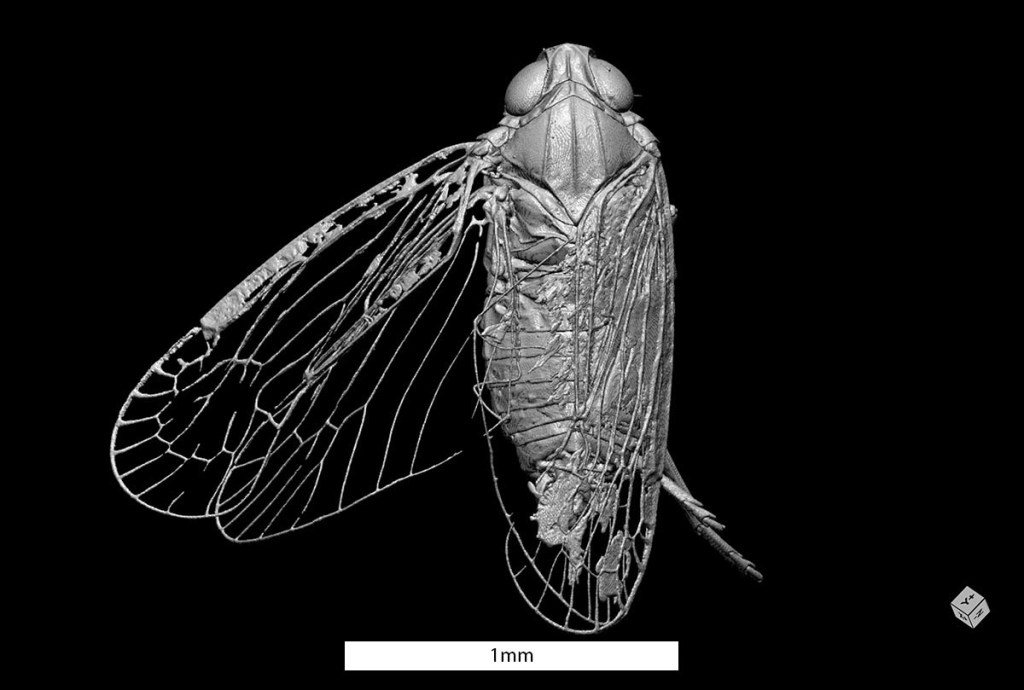

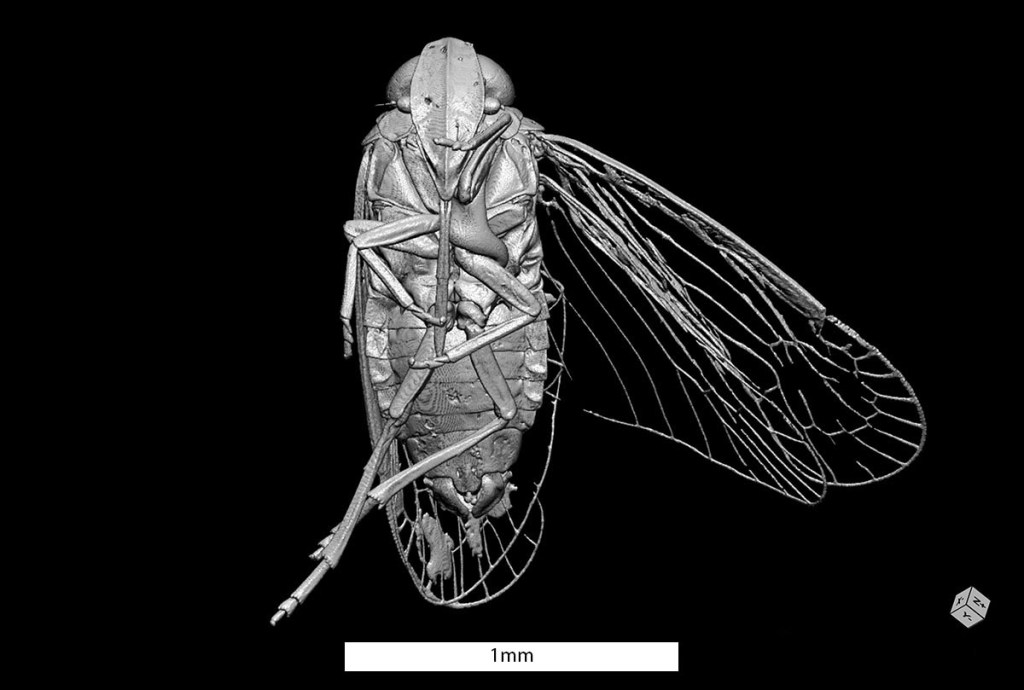

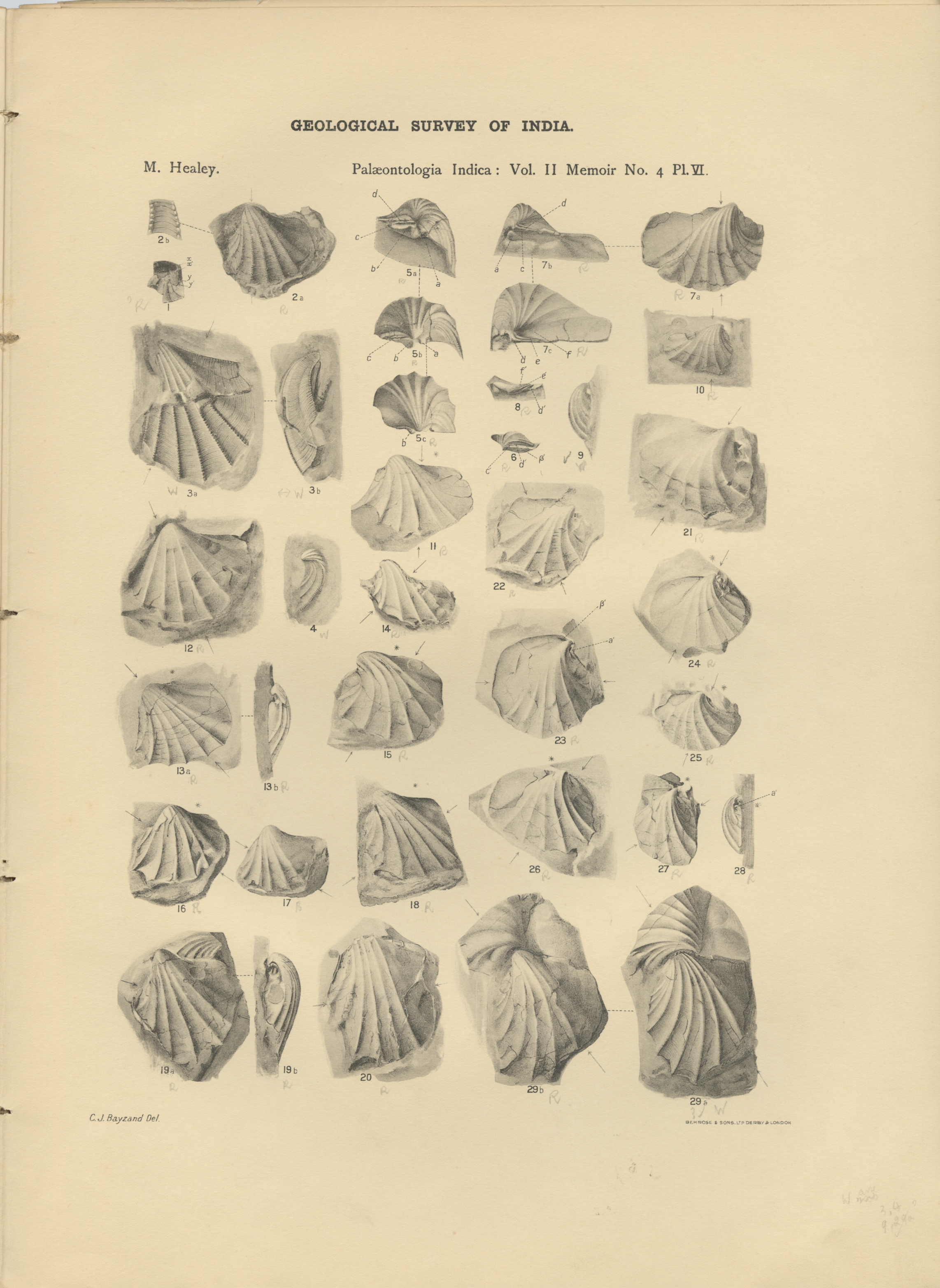

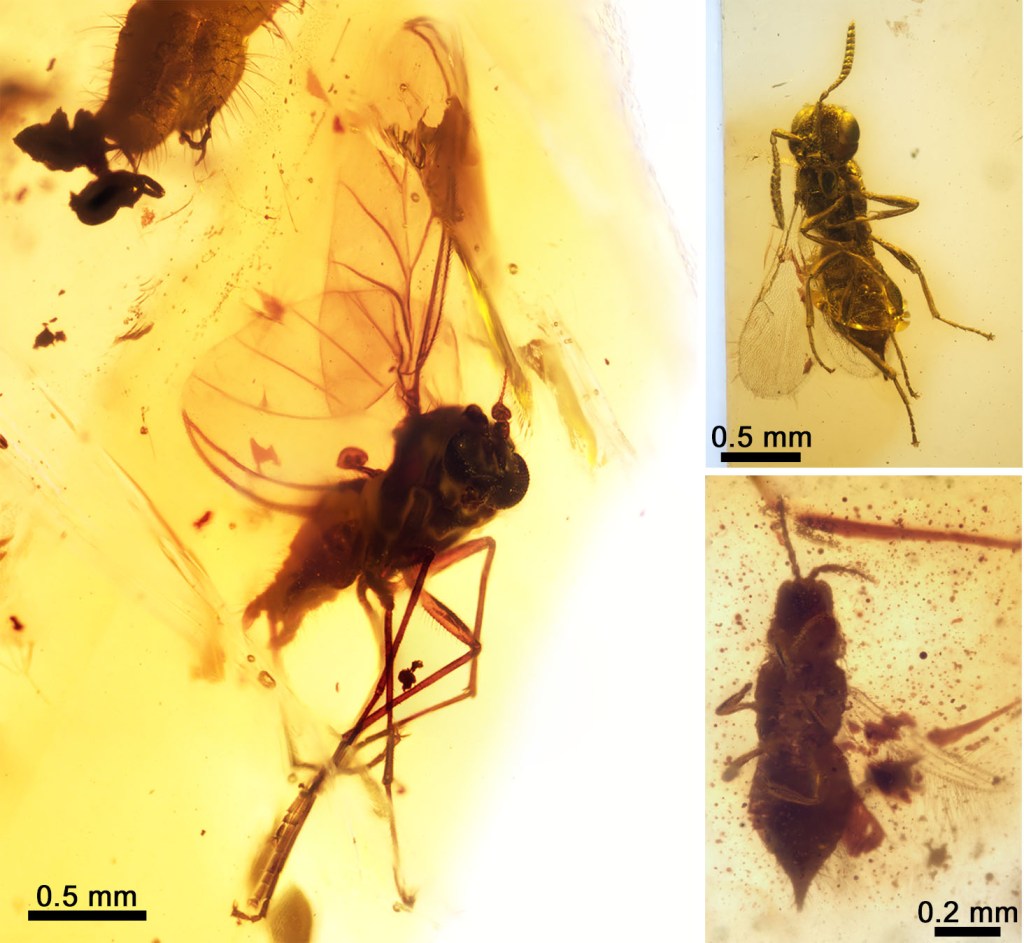

As palaeontologists, we normally use fossils to reveal the history of life. Fossils tend to preserve larger animals with hard shells or skeletons—creatures such as trilobites, ammonites, dinosaurs, and mammoths. However, the first complex organisms were microscopic and lacked such hard parts. As a result, their soft and fragile cells rarely fossilised. Put simply, we have found it a major challenge to trace the origins of complex life with fossils.

I have argued that finding rocks made up of antibacterial clay minerals holds the key. These minerals can slow the decay of organic cells long enough for them to survive as fossils. The Little Dal Group contains ~900-million-year-old rocks that are rich in just such clays, making it a prime target for new fossils that might help us unravel the origins of biological complexity.

I was joined in Canada by my DPhil student, George Wedlake, from the Department of Earth Sciences. Together we spent two weeks collecting over 100 rock samples. The samples record an ancient tropical sea not unlike the Bahamas today, where early complex life likely flourished.

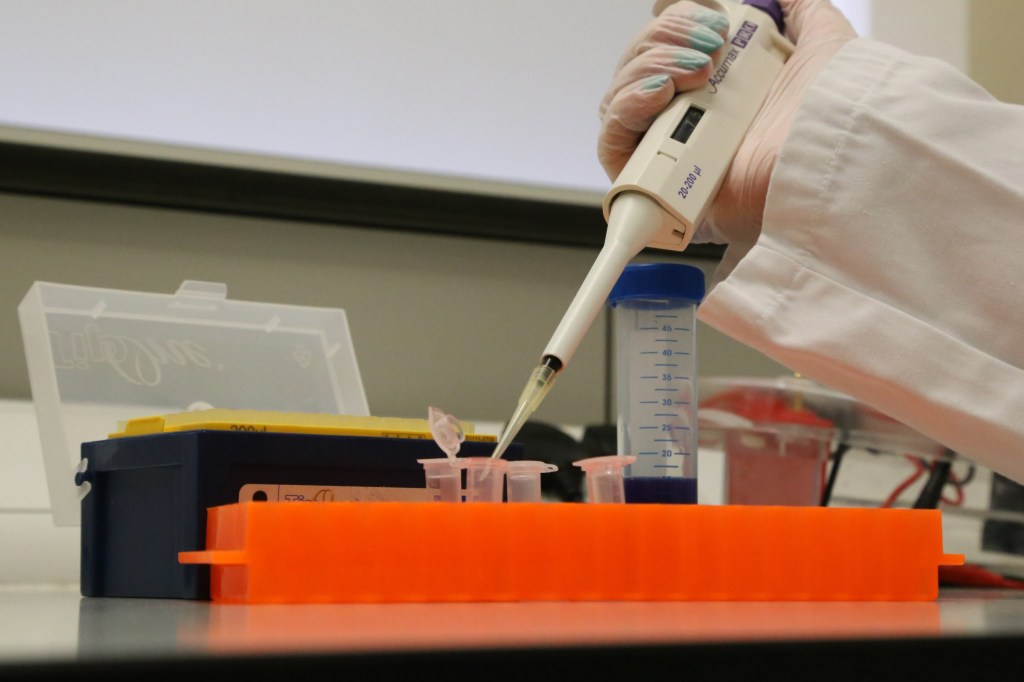

Back in Oxford, at the Museum of Natural History, George and I are now examining the samples; dissolving the rocks with hydrofluoric acid to extract and study the tiny fossils. We hope these new fossils will transform our understanding of how complex life first took hold on our planet.

Our fieldwork was funded by a Royal Society University Research Fellowship and by the Oxford NERC Environmental Science Doctoral Training Partnership. It was conducted under permit and with the support of the Sahtú Dene people.