The ‘birth’ of dinosaurs

by Hilary Ketchum, Earth Collections manager

In April 1842, 175 years ago this year, the dinosaurs were created – in a taxonomic sense at least. In a landmark paper in the Report for the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Richard Owen, one of the world’s best comparative anatomists, introduced the term ‘Dinosauria’ for the very first time.

Owen coined the term using a combination of the Greek words Deinos, meaning ‘fearfully great’, and Sauros, meaning ‘lizard’, in order to describe a new and distinct group of giant terrestrial reptiles discovered in the fossil record. He based this new grouping – called a clade in taxonomic terms – on just three genera: Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus.

In the Museum’s collections are some specimens of those three original dinosaurs, collected and described during this exciting early period of palaeontology. These discoveries, amongst others, helped to revolutionise our understanding of extinction, deep time, and the history of life on earth, and paved the way for the theory of evolution by natural selection.

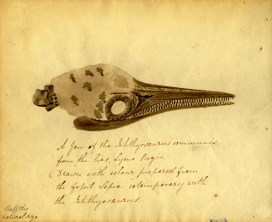

Megalosaurus

A nine metre long, 1.4 tonne carnivore that roamed England during the Middle Jurassic, about 167 million years ago, Megalosaurus has the accolade of being the world’s first named dinosaur. It was described by William Buckland, the University of Oxford’s first Reader in Geology, in 1824, and was discovered in a small village called Stonesfield, about 10 miles north of Oxford. The toothy jawbone of Megalosaurus is on display in the Museum.

Iguanodon

Iguanodon was a plant-eating reptile with a spike on the end of its thumbs, and teeth that look like those of an iguana, only 10 times bigger! Iguanodon lived in the Lower Cretaceous, around 130 million years ago and was named by Gideon Mantell in 1825.

When first discovered, Iguanodon’s spike was thought to go on its nose, like a rhinoceros or a rhinoceros iguana, rather than on its thumb, which is rather unique. In fact, we still don’t know why Iguanodon had such prominent thumb spikes.

Hylaeosaurus

A squat, armoured, plant-eating dinosaur with long spines on its neck and shoulders. It is the least well known and smallest of the three dinosaurs originally described, but arguably the cutest. Hylaeosaurus was also named by Gideon Mantell, in 1833.

The exact specimen used by Mantell to describe Hylaeosaurus armatus is in a big block of rock in the Natural History Museum in London. But recently I spotted a specimen in our collections that Mantell had sent to William Buckland in 1834. It has the following label with it, written by Mantell himself:

Extremity of a dorsal spine of the Hylaeosaurus from my large block –

Perhaps Mantell just snapped a bit off to send to his friend. Or perhaps more likely, it was one of the broken fragments Mantell said were lying near the main block when it was dug out of the ground.

*

From just three genera included in Dinosauria in 1842, we now have around 1,200 species nominally in the group. The study of dinosaurs has come a long way since those early days; new finds, new technologies, such as micro CT scanning and synchrotron scanning, and new statistical techniques are helping us to better understand these iconic animals and re-evaluate older specimen collections.

The Museum’s dinosaur specimens are exceptionally historically important, but are still used heavily by scientists from across the world for their contemporary research. This is something that I think William Buckland, Gideon Mantell and Richard Owen would be very pleased about.

The one that got away…

Although Owen didn’t know it, other dinosaurs were known in 1842, including Cetiosaurus, the ‘whale lizard’. When Owen named it in 1841, he thought it was a giant marine reptile that ate plesiosaurs and crocodiles. By the following year, he suggested it was actually a crocodile that had webbed feet and used its tail for propulsion through the water.

It wasn’t until 1875, after more substantial remains had been found that Owen recognised Cetiosaurus as a land-living sauropod dinosaur. Interestingly, however, research published last month presented a new hypothesis for dinosaur relationships which, if the previous definition of Dinosauria had been adhered to, would have placed all sauropods outside of the group. So perhaps Owen’s earlier omission wasn’t so wrong after all.