Conservation in the Genomic Era

HAVE DNA TECHNOLOGIES REPLACED THE NEED FOR MUSEUMS?

By Sotiria Boutsi, Intern

I am PhD student at Harper Adams University with MSc in Conservation Biology, currently doing a professional internship at the Museum of Natural History in the Public Engagement office. My PhD uses genomic data to study speciation in figs and fig wasps.

The year 1995 marked the first whole-genome sequencing for a free-living organism, the infectious bacterium Haemophilus influenza. Almost three decades later, biotechnological advances have made whole-genome sequencing possible for thousands of species across the tree of life, from ferns and roses, to insects, and – of course – humans. Ambitious projects, like the Earth BioGenome Project, aim to sequence the genomes of even more species, eventually building the complete genomic library of life. But do these advancements help us with conservation efforts? Or are the benefits of biotechnology limited to industrial and biomedical settings?

The value of genetic information is becoming increasingly apparent: from paternity tests and DNA traces in forensic investigations, to the characterization of genes related to common diseases, like cancer, we are becoming familiar with the idea that DNA can reveal more than meets the eye. This is especially the case for environmental DNA, or eDNA — DNA molecules found outside living organisms. Such DNA is often left behind in organic traces like tissue fragments and secretions. Practically, this means that water or air can host DNA from organisms that might be really hard to observe in nature for a variety of reasons — like being too small, too rare, or just too shy.

So, how do we determine which species left behind a sample of eDNA? The method of identifying a species based on its genomic sequence is called barcoding. A barcode is a short genomic sequence unique to a species of organism. Therefore, every time we encounter a barcode sequence, whether it is taken from a living animal or eDNA, we can associate it to the species which it belongs to.

When we have a mix of different species to identify, things become a bit more complicated. Sometimes we will pick up samples which represent an entire ecological community, and must sort through these using a process called meta-barcoding.

How does meta-barcoding work? Well, we want to be able to identify species based on the shortest possible species-specific sequence. Traditional laboratory methods for DNA amplification (PCR) are combined with DNA sequencing to read the DNA sequences found in any given water or air sample. Then, having a database of reference genomes for different species can serve as the identification key to link the sample sequences to the species they originated from.

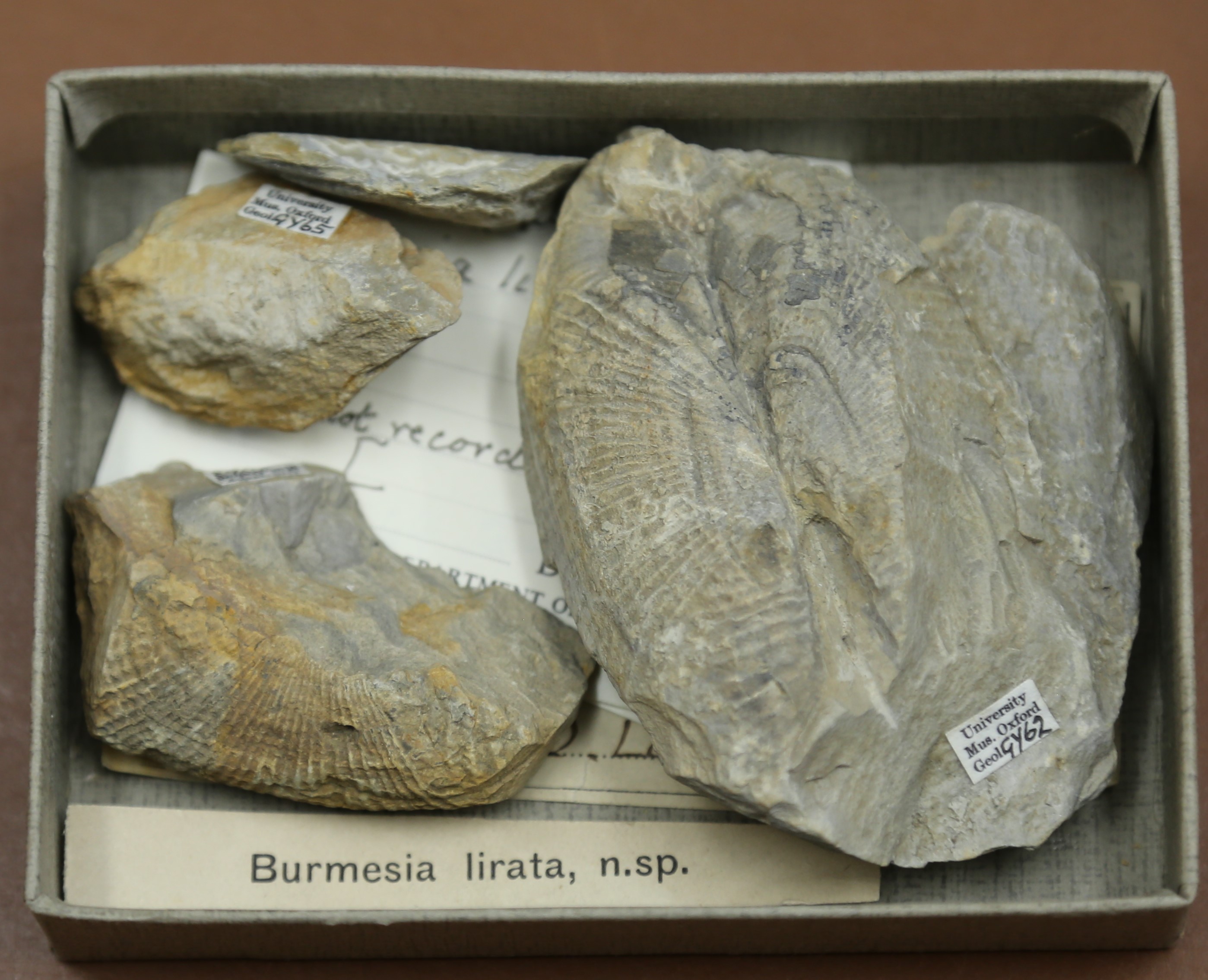

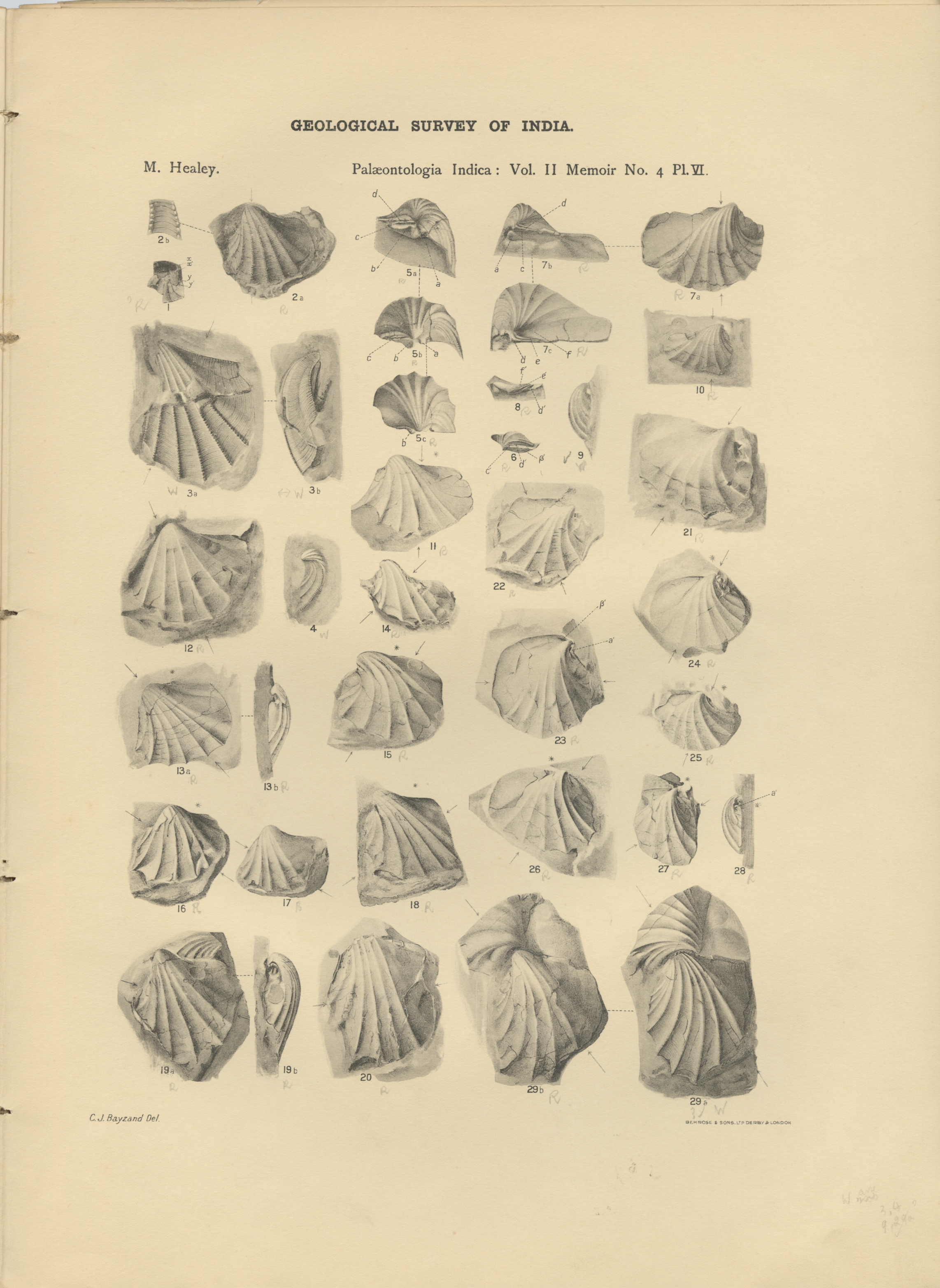

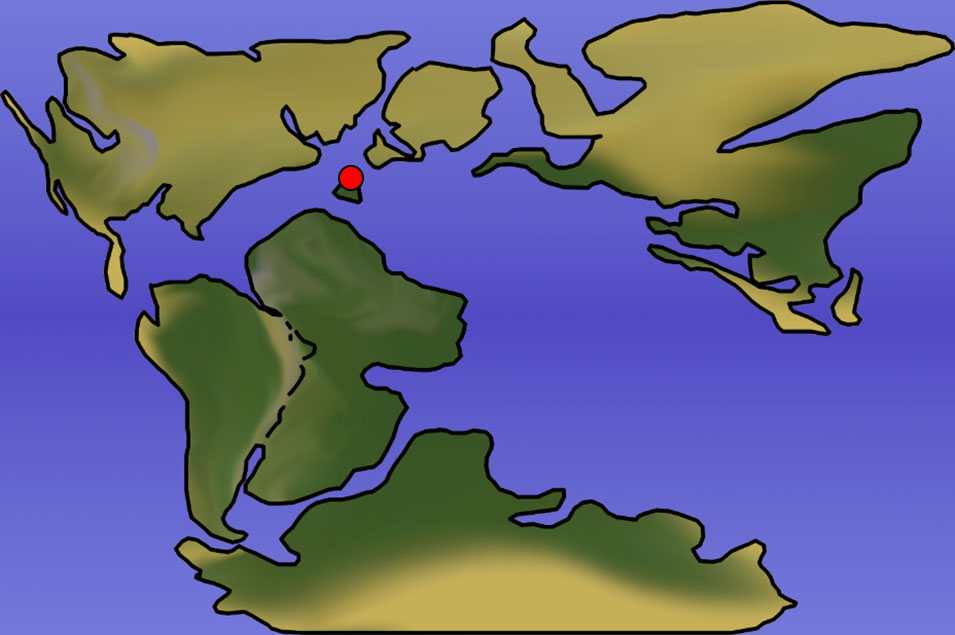

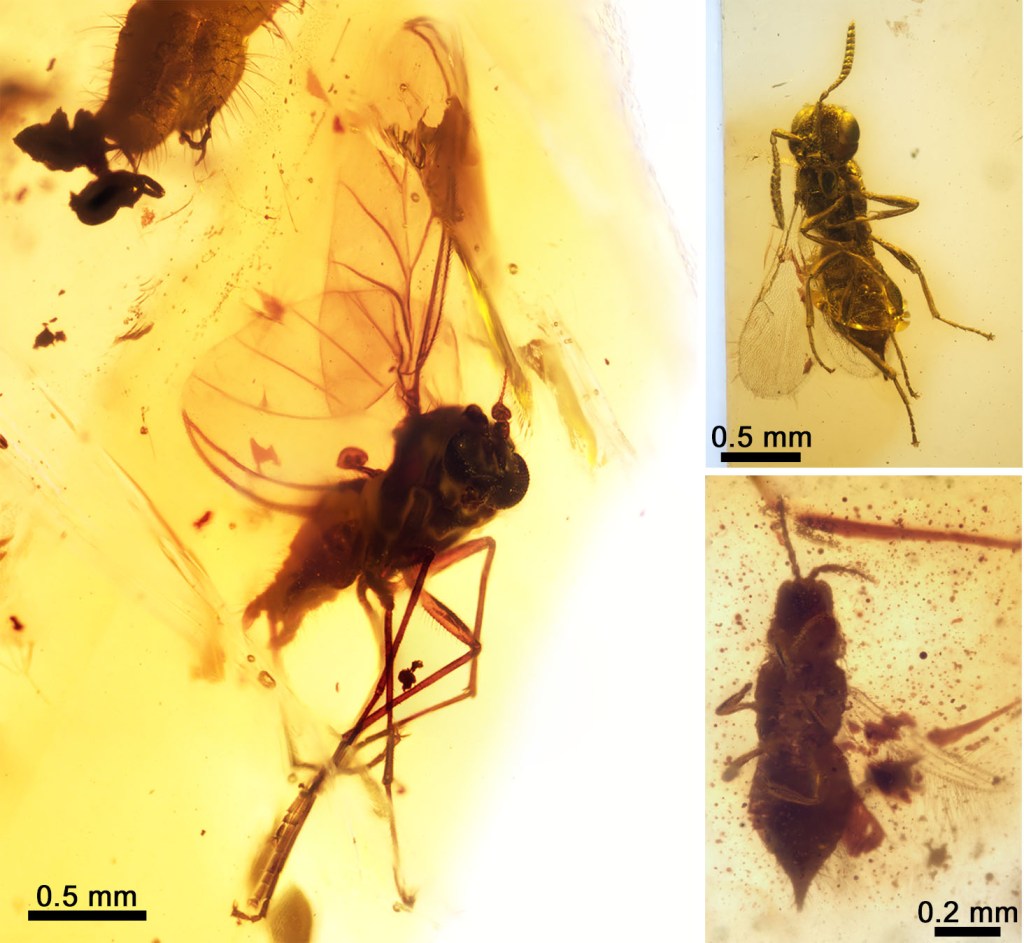

So, what does this mean for the future of ecology and conservation? Traditional monitoring of biodiversity can involve capturing and killing live animals. This is the case with insect specimens found in museums across the world. Although museum collections are irreplaceable as a record of the history of wild populations, regular monitoring of endangered species should rely on non-invasive methods, such as meta-barcoding of eDNA. Indeed, eDNA has been used to monitor biodiversity in aquatic systems for almost a decade. Monitoring terrestrial ecosystems through air samples is now also becoming possible, opening new possibilities for the future of conservation.

During March, the Museum delivered practical molecular workshops in our laboratory, reaching more than 200 Key Stage 5 students. Students have had the opportunity to learn about the use of eDNA in ecology, as well as get some hands-on experience in other molecular techniques. These include DNA extraction, PCR, the use of restriction enzymes, and gel electrophoresis. The workshops were delivered by early-career researchers with practical experience in working in the laboratory, as well as Museum staff with a lot of experience in delivering teaching. Through the Museum’s workshops, which run regularly, the next generation of scientists is introduced not only to both human genetics, but also molecular tools used in ecological research, which without a doubt will become increasingly relevant for future conservationists.

We cannot conserve what we do not know. Monitoring biodiversity is the cornerstone of any conservation practice. Doing it efficiently, by making use of both traditional as well as molecular tools, can allow more accurate predictions for the future of biodiversity under the lens of anthropogenic change.

More Information:

- Ruppert et al. 2019 “Past, present, and future perspectives of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding: A systematic review in methods, monitoring, and applications of global eDNA,” https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00547.

- Airborne environmental DNA metabarcoding for the monitoring of terrestrial insects—A proof of concept from the field, https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.290

- The Earth BioGenome Project 2020: Starting the clock, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2115635118

- The Museum’s molecular workshops: search A Question of Taste in Key Stage 5 School Visits – Science | Oxford University Museum of Natural History

British Insect Collections: HOPE for the Future is an ambitious project to protect and share the Museum of Natural History’s unique and irreplaceable British insect collection. Containing over one million specimens – including dozens of iconic species now considered extinct in the UK – it offers us an extraordinary window into the natural world and the ways it has changed over the last 200 years. The HOPE for the Future project is funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, thanks to National Lottery players.