Ubiquitous and Inconspicuous

THE INVISIBLE HISTORY OF THE MUSEUM’S GLASS DISPLAY CASES

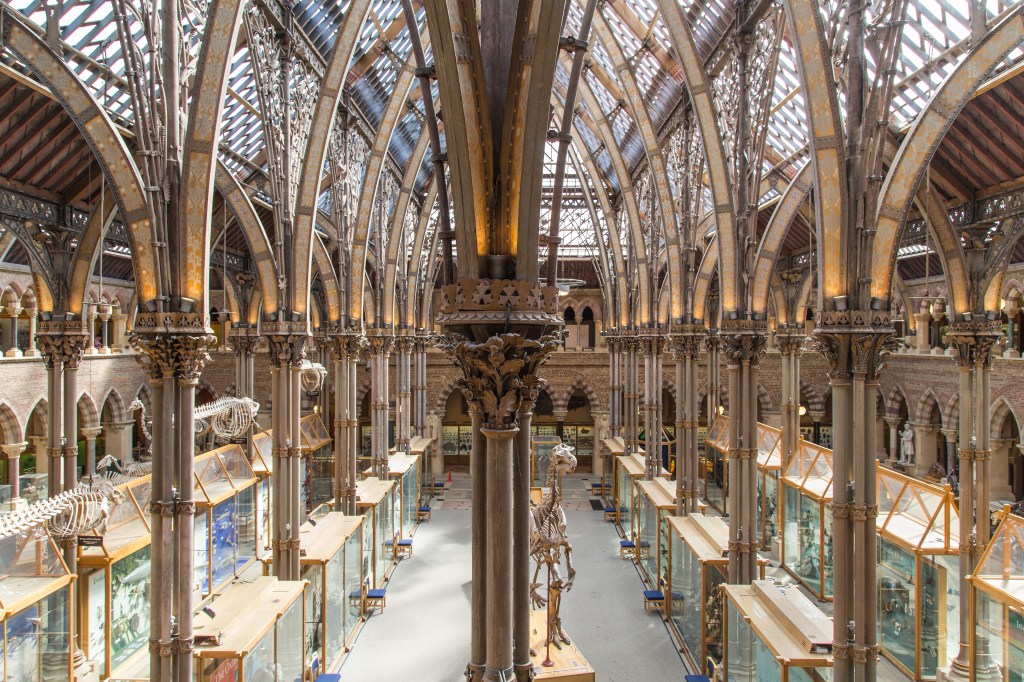

Glass cases play an integral role in museums and galleries, but they are designed to be overlooked and ignored. In this blog post, Librarian and Archivist Danielle Czerkaszyn uses research collected by Helen Goulston (AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Partnership PhD Candidate) to uncover the invisible history of OUMNH’s glass display cases and considers how they have evolved alongside the museum during its 160-year history.

Since 2018, the Museum has been working to refresh its Main Court by installing new permanent displays. This morning, we placed the final specimen in our brand new “Open Oceans” display, concluding the latest phase of the redisplay project. The “Open Oceans” display is housed in one of eight new conservation-grade glass cases installed last year. While some visitors have welcomed the new cases, others have mourned the loss of the wooden cases or questioned why they needed to be replaced. Others have wondered why the tops of the new glass cases have roofs with different heights. To answer these questions, we need to dive into the museum archive…

A CASE HISTORY

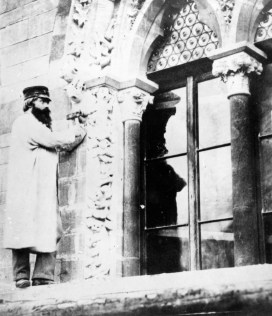

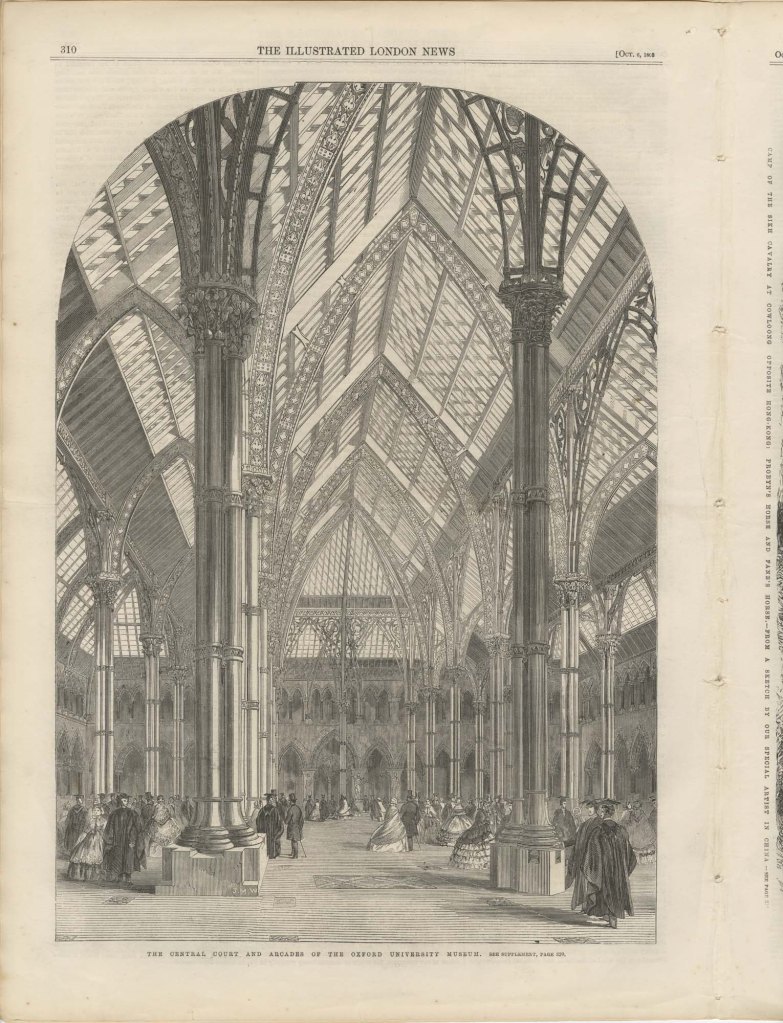

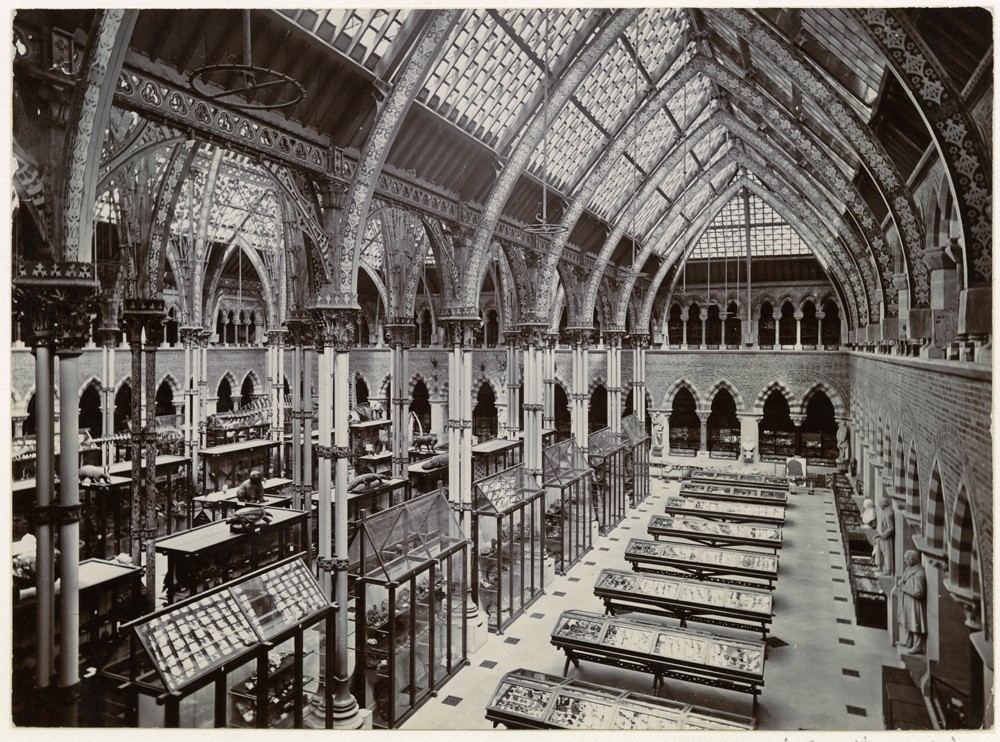

When visitors arrived at the newly-opened museum in 1860 they would have been greeted by an empty central court, devoid of displays. While the fabric of the building was more or less complete, and preparation for the installation of displays had already begun, the university’s scientific and natural history collections had not yet been transferred to the building.

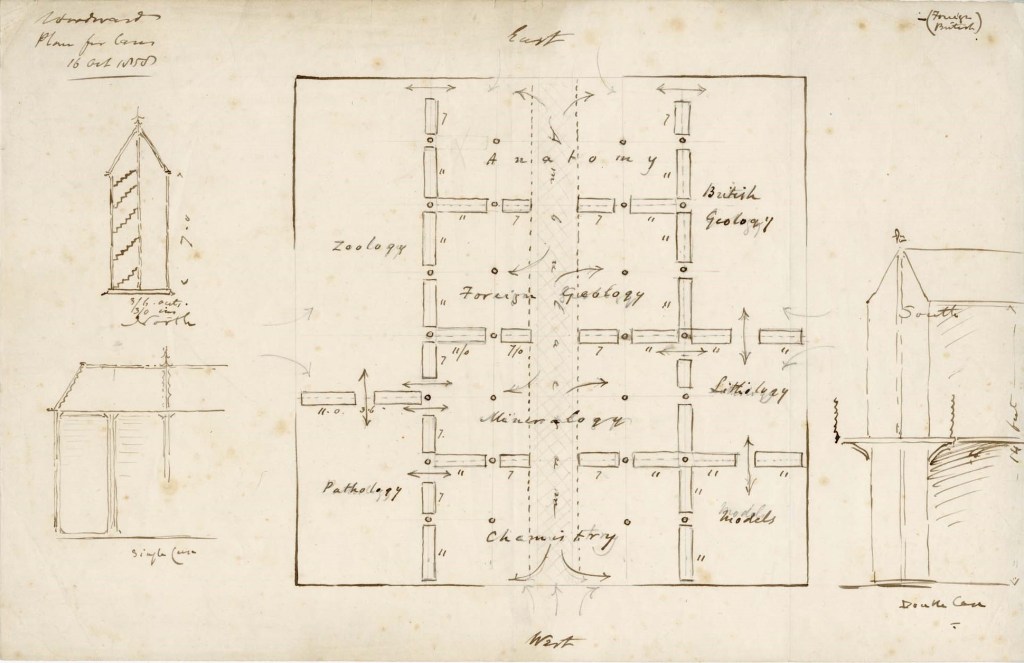

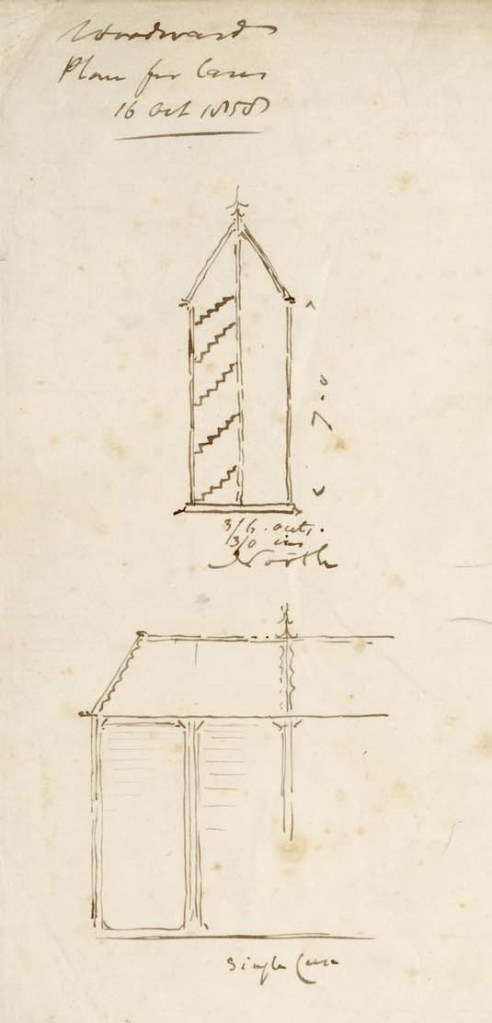

A sketch in the archive dated 16 October 1858 by architect Benjamin Woodward shows an early plan for the display cases to be arranged between the iron columns in the Main Court, allowing visitors to circulate among the exhibits, with display cases echoing the Gothic revival architecture. The right of the document shows grand double-height displays with a central balustrade that were never realised, but cases similar to those on the left would be ordered in January 1862.

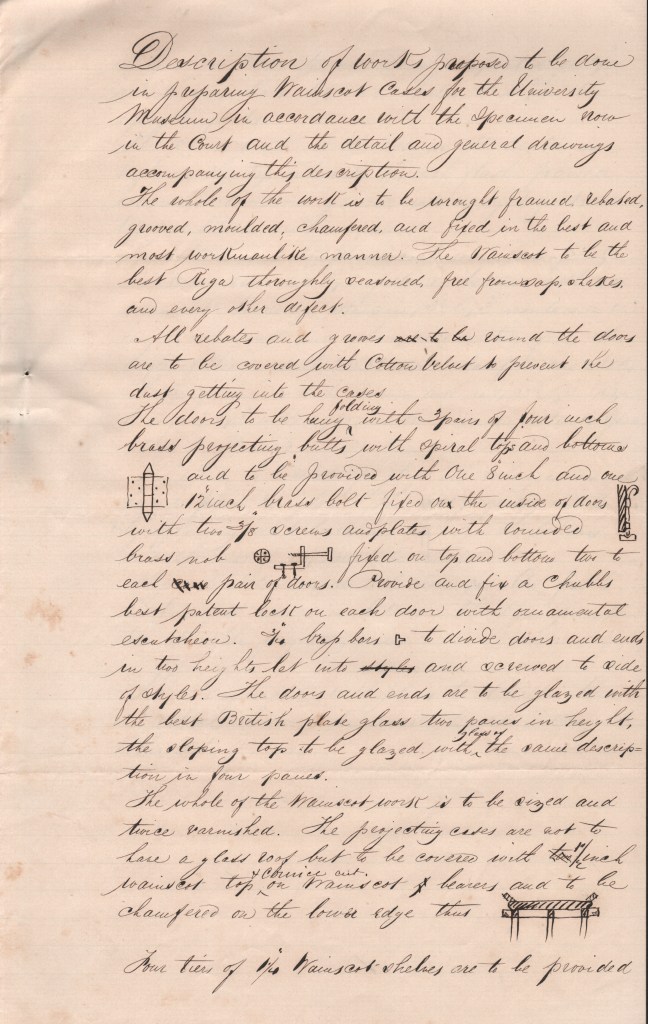

The 1862 tender document written by William Bramwell, Clerk of Works at the Museum, shows two types of upright display cases ordered for installation between the iron columns — some with pitched roofs and others with flat tops, which were considerably cheaper. Though the design of the cases resembles Woodward’s original sketches, the tender included detailed specifications that addressed the practicalities of displaying specimens, such as cotton velvet door linings to stop dust from getting in.

In addition to the upright centre court cases, ten table cases were ordered from the high-end London cabinet makers, Jackson and Graham, at a cost of £344.10. The same firm was also commissioned to fit the tall wall cases in the outer corridors. Plans and photographs from the archive show that the installation of these cases was piecemeal and it wasn’t until 1866 that all the display cases were fully in place.

WHY REPLACE THE CASES?

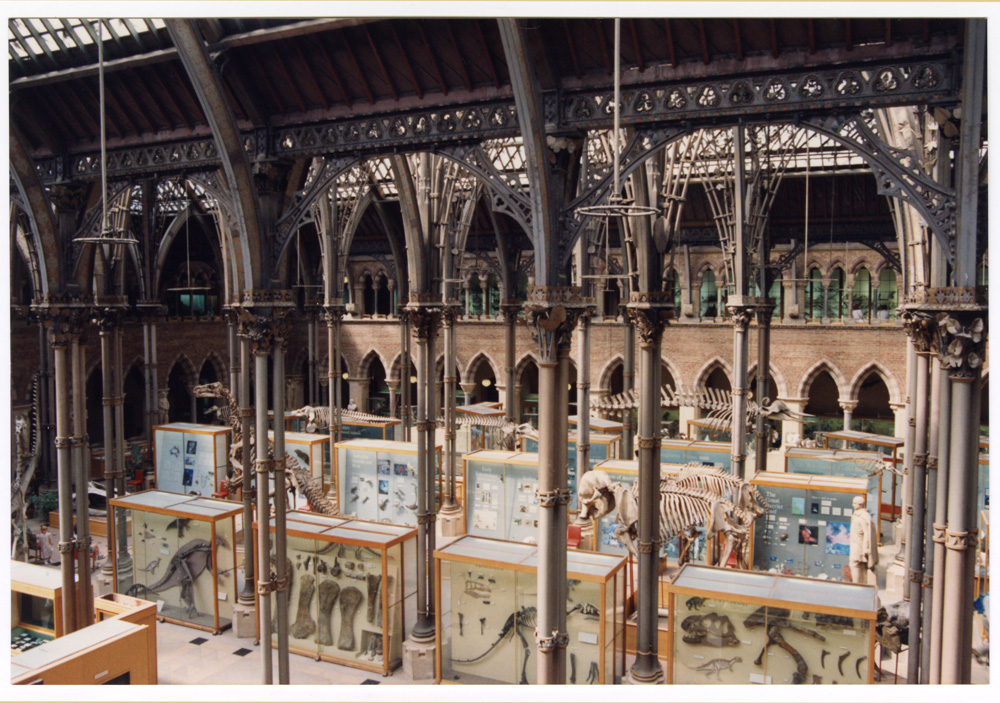

The wooden display cases that we have been replacing may look old, but few of the original cases from 1866 survive. While some of the old display cases were moved behind the scenes for preservation, others found homes in different museums or were disposed of when they were beyond repair. The most recent timber-framed cases in the Main Court are 20th-century replicas that have been heavily modified, particularly in the late 1960s-early 1970s, and again in the early 2000s when the clear acrylic roofs were added. Some of these modifications affected the stability of the cases, particularly when the doors were opened, making them unsafe for staff to access. Other modifications meant the cases were no longer dust or pest-proof, which poses a risk to specimens.

As these wooden display cases neared the end of their life, the museum and Oxford University Estates worked with Oxford City Council and Historic England to approve the replacement of the cases and ensure the redevelopment was historically sensitive to our Grade 1 listed Victorian building.

For this reason, the new cases retain the original 1866 arrangement and are built to the same dimensions. We have also returned to the original form, including outer aisle cases with alternating pitched and flat roofs. It was decided early on that the new cases would not be lined in wood because timber can be detrimental to the conservation of certain specimens. However, the design of the edges of the new cases sought to mirror the craftmanship of the 1866 cases by emulating the beading on the edges – albeit much more subtly, and in bronze rather than timber – complementing the colours of the ironwork in the museum roof.

A CASE FOR THE FUTURE

The new glass cases are built by museum showcase experts ClickNetherfield and provide a stable, pest-proof environment for our delicate and historically important specimens. Their design artfully captures the character of the museum building, while still focusing the visitor’s attention on their contents. It is hoped that the new displays will last for at least another two decades, and the cases even longer. During that time, millions of eyes will be cast over our displays, but the glass cases that protect them may barely even be noticed.