by Paul Smith, Museum director

One of the unusual things about the collections in the Museum is that some of the specimens date back hundreds of years, and so have been researched by generation after generation. Sometimes these specimens have been damaged and repaired, and in some cases this has happened many times, leaving a complex history of research and conservation.

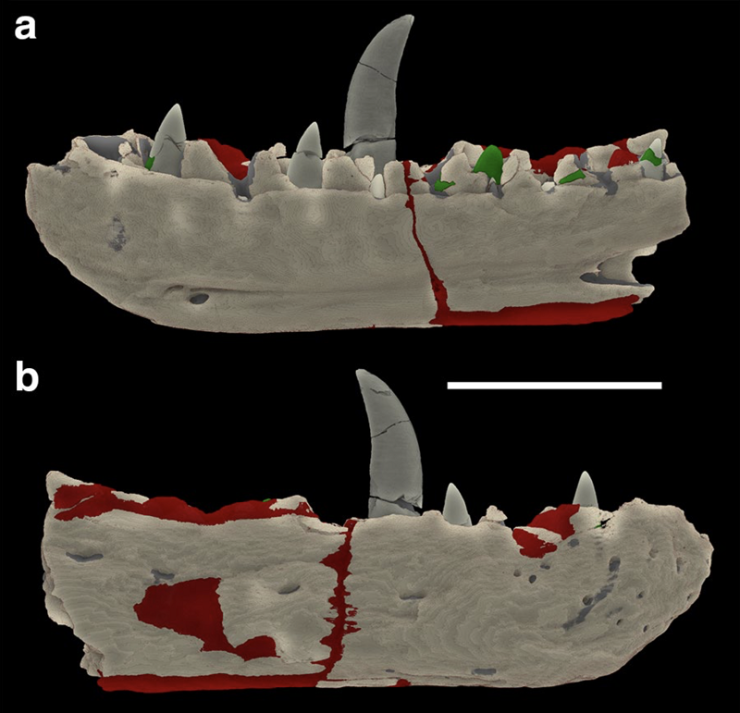

One high profile example is the type specimen of the theropod dinosaur Megalosaurus bucklandii – the world’s first scientifically described dinosaur. This specimen itself is the lower jaw, pictured above, which has been in the collections of Oxford University since 1797 at the latest.

Working with the Centre for Imaging, Metrology, and Additive Technology (CiMAT) at WMG, University of Warwick, we have been unraveling the conservation and repair history of the fossilised jaw using an innovative combination of modern technologies.

Earlier studies had mapped the presence of plaster used for repair, but X-ray CT scanning of the type used in medical procedures rapidly revealed a number of different phases of repair. In each of these repairs the plaster was of different composition and was used in different places.

One type, shown in red on the image above, was used to infill fractures and to make the specimen more robust; a second type, shown in green, was used to repair the teeth and, in some cases, to recreate the teeth. Interestingly, the extent of plaster revealed by the CT scanning is actually less than previously interpreted with the naked eye.

The two types of plaster were then analysed chemically to better understand their historical use, revealing quite different compositions. The more abundant ‘red’ plaster is mixed with quartz sand and calcite grains, possibly from the rock matrix surrounding the fossil, to make it look more similar.

Carbon is also abundant and grains rich in lead are present. Carbon is not common in the rock itself, and the carbon in the plaster has probably come from a varnish such as shellac being used to coat the repair. The presence of lead was more puzzling. Further analysis eventually showed that the grains were made of red lead – lead tetroxide – which was used historically as a pigment in paint. The red lead in the repair may have been used to colour the plaster, but it may also have been applied to make the density of the plaster more similar to that of the fossilized bone, and so replicate the weight of the specimen better.

The second type of plaster, used to repair the teeth, lacks the lead of the first type but contains barium. Barium hydroxide was often used as a consolidant and sealant for plaster, which would explain its use here.

Having a full understanding of the repair history and the position and extent of plaster helps us in a number of ways. It allows researchers to understand which parts of the lower jaw are original and anatomically reliable, and it helps the curators and conservators to know which parts of the specimen are more fragile during handling and display.

By combining cutting-edge scanning technologies with heritage material we are able to shed new light on the conservation history, and future, of important specimens such as Megalosaurus bucklandii.

Read the full paper here.

[…] 31 May 2018 video is called Megalosaurus bucklandii jaw scan by WMG, University of […]

[…] second dinosaur – and the first herbivorous one – to be named (the first was the carnivorous Megalosaurus – another famous Museum […]