High-tech insect origami

By Dr Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente, Research Fellow

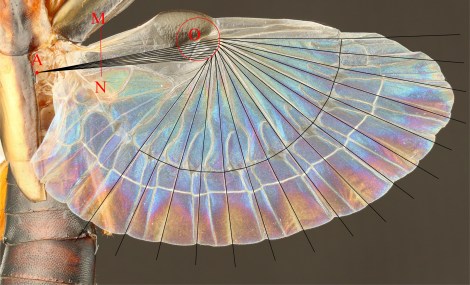

Earwigs are fascinating creatures. Belonging to the order Dermaptera, these insects can be easily recognised by their rear pincers, which are used for hunting, defence, or mating. But perhaps the most striking feature of earwigs is usually hidden – most can fly with wings that are folded to become 15 times smaller than their original surface area, and tucked away under small leathery forewings.

With protected wings and fully mobile abdomens, these insects can wriggle into the soil and other narrow spaces while maintaining the ability to fly. This is a combination very few insects achieve.

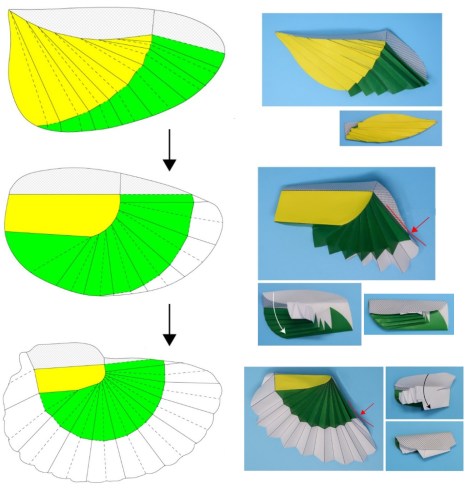

I have been working on research led by Dr Kazuya Saito from Kyushu University in Japan, which presents a geometrical method to design earwig wing-inspired fans. These fans could be used in many practical applications, from daily use articles such as fans or umbrellas, to mechanical engineering or aerospace structures such as drone wings, antennae reflectors or energy-absorbing panels!

Dr Saito came to Oxford last year for a six-month research stay at Prof Zhong You’s lab, in the Department of Engineering Science at the University of Oxford. He introduced me to biomimetics, an ever-growing field aiming to replicate nature for a wide range of applications.

Biological structures have been optimised by the pressures of natural selection over tens of millions of years, so there is much to learn from them. Dr Saito had previously worked on the wing folding of beetles, but now he wanted to tackle the insect group that folds its wings most compactly – the earwigs.

He was developing a design method and an associated software to re-create and customise the wing folding of the earwig hind wing, in order to use it in highly compact structures which can be efficiently transported and deployed. Earwigs were required!

Here at the Museum we provided access to our insect collections, including earwig specimens from different species having their hind wings pinned unfolded. These were useful to inform the geometrical method that Saito had been devising.

Dr Saito was also interested in learning about the evolution of earwigs and finding out when in deep time their characteristic crease pattern established. Some fossils of Jurassic earwigs show hints of possessing the same wing structure and folding pattern of their relatives today.

However, distant earwig relatives that lived about 280 million years ago during the Permian, the protelytropterans, possessed a different – yet related – wing shape and folding pattern. That provided the chance to test the potential and reliability of Saito’s geometrical method, as all earwigs have very similar wings due to their specialised function.

The geometrical method turned out to be successful at reconstructing the wing folding pattern of protelytropterans as well, revealing that both this extinct group and today’s earwigs have been constrained during evolution by the same geometrical rules that underpin the new geometrical design method devised by Dr Saito. In other words, the fossils were able to inform state-of-the-art applications: palaeontology is not only the science of the past, but can also be a science of the future!

We were also able to hypothesise intermediate extinct forms – somewhere between protelytropterans and living earwigs – assuming that earwigs evolved from a form closely resembling the protelytropterans.

As a collaboration between engineers and palaeobiologists, this research is a great example of the benefits of a multidisciplinary approach in science and technology. It also demonstrates how even a minute portion of the wealth of data held in natural history collections can be used for cutting-edge research, and why it is so important to keep preserving it for future generations.

Soon these earwig-inspired deployable structures might be inside your backpacks or used in satellites orbiting around the Earth. Nature continues to be our greatest source of inspiration.

Original paper: Saito et al. (2020). Earwig fan designing: biomimetic and evolutionary biology applications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.