Gené dor left open

|

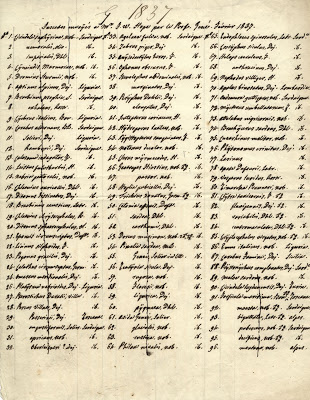

| List of specimens that Gené sent to Hope |

|

| The type specimen of Chelotrupes hiostius |

|

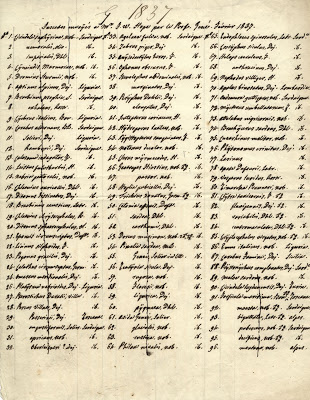

| List of specimens that Gené sent to Hope |

|

| The type specimen of Chelotrupes hiostius |

Today marks the 244th birthday of William ‘Strata’ Smith, a very important figure in the history of English geology and to the Museum, so we thought it only appropriate that we mark this day.

Despite being born to humble beginnings in Churchill, Oxfordshire in the late 18th Century, Smith single-handedly mapped the geology of Great Britain and created the first geological map of England and Wales, which was published in 1815. He managed this amazing feat through his observation of the layers, or strata, beneath the earth and the fossils found within them. His work as a Land Surveyor and Engineer for both Mining and Canal companies proved to be the perfect opportunity to complete his work, allowing him to travel the country to complete contracts and still make his observations.

While this accomplishment was undoubtedly remarkable, Smith unfortunately didn’t receive the recognition for his work he so deserved until late in life. His lack of formal education and his family’s working class background made him an outcast to most of higher society at the time. It wasn’t until just a few years before he passed away, in 1839, that he received any recognition for his ingenious contribution to the science of geology, receiving a number of awards, including the prestigious Wollaston Medal and an honorary degree.

We are very fortune to have a large number of Smith’s papers here at the Museum, and to have recently received generous funding from Arts Council England to catalogue and digitise his collection. As uncle, guardian and teacher to the Museum’s first keeper John Phillips, Smith’s papers have long been housed within our archive and are an important resource into the history of geology and geological mapping in Britain. This funding will give us the opportunity to make them available online to the public for the first time.

William Smith Online will be available early next year, but work is well underway behind the scenes. The website will launch a number of events over 2014 through to 2015, to celebrate the bicentenary of Smith’s geological map of England and Wales, both here in the museum and around the country. Watch this space, or follow us on twitter to keep updated on this exciting project!

Kate Santry, Head of Archival Collections

As readers of this blog will be well aware, most of the Museum’s exhibits are closed up and under wraps. But because visitors on their way to the Pitt Rivers Museum still pass through the Museum of Natural History we have decided to install a new changing display of a few treasures from the collection.

The series is called Presenting… and it kicks off with a selection of objects belonging to William John Burchell, a 19th century explorer and naturalist, who died 150 years ago this month. He left a treasure trove of natural history specimens, many of which are now in the Museum.

You can see the display for real just inside the entrance of the Museum, and you can read more about it on our website.

Scott Billings, Communications coordinator

With the view from the gallery looking quite different these days, I was inspired to pull out some historic photographs from the archive of the roof’s original construction. Hoping for a glimpse of what to expect once it’s returned to its original glory, I also discovered some interesting facts about the architectural feats required to raise the roof the first time around.

The Museum was designed by the famous Irish architectural team, Deane and Woodward, which won the contract through a contest held by the Museum Delegates in 1854 (the Museum opened in 1860). One of the few stipulations of the contest was that the design had to feature a glass and iron roof to cover the court, and that the Museum had to be built for less than £30,000.

The design of the roof was quite innovative for the time, but the budget for construction was tight: originally £5,216. However, Skidmore, the iron-worker employed to execute the building of the roof supports, proposed that it could be done for much less if wrought iron, a cheaper and more malleable metal than cast iron, was used instead.

In fact, a further £2,000 was needed to complete this magnificent and heavy piece of construction because of this miscalculation on Skidmore’s part: the stronger cast iron was indeed needed to construct the load bearing pillars that held the glass roof safely in place. Wrought iron was still used for some of the work and, being more malleable, it proved the perfect choice for the intricate detailing that was planned for the pillars.

As Skidmore himself stated, it “held out the possibility of uniting artistic iron-work with the present tubular construction, and a prospect of a new feature in the application of iron to Gothic architecture.”

And so it was. More than 150 years later the roof remains visually impressive, even if it is a little leaky around the glass work. The picture below shows the current preparations for repairs that will restore the roof to its original splendour, ready for the Museum’s reopening in 2014.

by Kate Santry, Head of Archival Collections

In 2013, 100 years after his death, we celebrate the life of Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), one of the greatest Victorian naturalists, travellers and collectors, a scientific and social thinker, early bio-geographer and ecologist, co-founder with Charles Darwin, of the theory of evolution through Natural Selection.

The Hope Entomological Collections (HEC) has many examples of species named after Wallace and of specimens collected by Wallace himself including species types such as Wallace’s giant bee.

|

| Megachile pluto described by B. Smith, 1869 is the largest bee species in the world. It occurs in Indonesia and builds its nest inside active termite nests. |

The OUMNH also has nearly 300 letters written by Wallace discussing scientific topics, social issues, his relationship with Charles Darwin, and family matters which have been scanned as part of the Wallace Correspondence Project (WCP). Recently, the WCP has launched a new searchable open access on-line database entitled ‘Wallace letters on-line‘. Staff and volunteers in the HEC have put in many hours of work in order to add our own holdings of letters and correspondance to this exciting project.

|

| A letter from A.R. Wallace to E.B. Poulton, a former curator of the Hope Entomological Collections. |

|

| The postcard above, written in Wallace’s handwriting reads as follows ‘Many thanks for the kind congratulations- Am feeling quite jolly! Alfred R Wallace’ |