What colour were the dinosaurs?

This article is taken from European research magazine Horizon as part of our partnership to share natural environment science stories with readers of More than a Dodo.

What colour were the dinosaurs? If you have a picture in your head, fresh studies suggest you may need to revise it. New fossil research also suggests that pigment-producing structures go beyond how the dinosaurs looked and may have played a fundamental role inside their bodies too.

The latest findings have also paved the way for a more accurate reconstruction of the internal anatomy of extinct animals, and insight into the origins of features such as feathers and flight.

Much of this stems from investigations into melanin, a pigment found in structures called melanosomes inside cells that gives external features including hair, feather, skin and eyes their colour – and which, it now turns out, is abundant inside animals’ bodies too.

‘We’ve found it in places where we didn’t think it existed,’ said Dr Maria McNamara, a palaeobiologist at University College Cork in Ireland. ‘We’ve found melanosomes in lungs, the heart, liver, spleen, connective tissues, kidneys… They’re pretty much everywhere.’

The discoveries in her team’s newest research, published in mid-August, were made using advanced microscopy and synchrotron X-ray techniques, which harness the energy of fast-moving electrons to help examine fossils in minute detail.

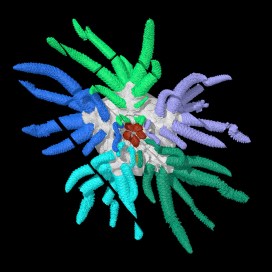

Using these, the researchers found that melanin was widespread in the internal organs of both modern and fossil amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals – following up a finding they made last year that melanosomes in the body of existing and fossil frogs in fact vastly outnumbered those found externally.

What’s more, they were surprised to discover that the chemical make-up and shape of the melanosomes varied between organ types – thus opening up exciting opportunities to use them to map the soft tissues of ancient animals.

Secondary

These studies also have further implications. For one, the finding that melanosomes are so common inside animals’ bodies may overhaul our very understanding of melanin’s function, says Dr McNamara. ‘There’s the potential that melanin didn’t evolve for colour at all,’ she said. ‘That role may actually be secondary to much more important physiological functions.’

Her research indicates that it may have an important role in homeostasis, or regulation of the internal chemical and physical state of the body, and the balance of its metallic elements.

‘A big question now is does this apply to the first, most primitive vertebrates?’ said Dr McNamara. ‘Can we find fossil evidence of this? Which function of melanin is evolutionarily primitive – production of colour or homeostasis?’

At the same time, the findings imply that we may need to review our understanding of the colours of ancient animals. That’s because fossil melanosomes previously assumed to represent external hues may in fact be from internal tissues, especially if the fossil has been disturbed over time.

Dr McNamara says her research has also shown that melanosomes can change shape and shrink over the course of millions of years, potentially affecting colour reconstructions.

Further complicating the picture is that animals contain additional non-melanin pigments such as carotenoids and what is known as structural colour, which was only recently identified in fossils. In 2016, a study by Dr McNamara’s team on the skin of a 10-million-year-old snake found that these could be preserved in certain mineralised remains.

‘These have the potential to preserve all aspects of the colour-producing gamut that vertebrates have,’ said Dr McNamara.

She hopes over time that these findings and techniques will together help us to much more accurately interpret the colours of ancient organisms – though in these early days, she doesn’t have examples of animals for which this has already changed.

We’re just at the tip of the iceberg when it comes to fossil colour research.

Dr Maria McNamara, University College Cork, Ireland

Deep time

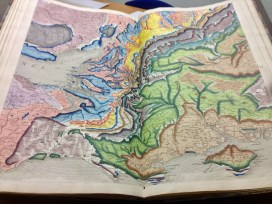

Many of the significant strides in this area have come out of a project that Dr McNamara leads called ANICOLEVO, which set out to look into the evolution of colour in animals over deep time – or hundreds of millions of years.

The project’s starting point was that previous animal colour studies largely omitted in-depth fossil analysis, leaving a significant gap by basing what we know about colour mainly on modern organisms.

But it has since led to even wider investigation. Dr McNamara says it is providing fresh hints on the kinds of biological structures and processes that are essential for survival in terrestrial and aquatic environments. ‘It looks like we’ll be able to look into much broader, exciting questions about what it means to be an animal,’ she said.

Part of her research on two fossils found in China even showed that flying reptiles known as pterosaurs had feathers, potentially taking the evolution of these structures back a further 80 million years to 250 million years ago. The fossils contained preserved melanosomes with diverse shapes and sizes, one of the tell-tale signs of feathers.

‘We were able to show for the first time that not only were dinosaurs feathered, but an entirely different group of animals, the pterosaurs, also had feathers,’ said Dr McNamara.

Another project she worked on, called FOSSIL COLOUR, compared the chemistry of colour patterns between fossil and modern insects. Again, says Dr McNamara, these don’t entirely map onto each other.

‘It’s already clear that the fossilisation process has altered the chemistry somewhat, so we’re doing experiments to try to understand these changes.’

What’s evident is that there’s lots still to find out about colour. ‘We’re just at the tip of the iceberg when it comes to fossil colour research,’ said Dr McNamara.

Thermoregulation

Other researchers agree that there’s more to animal colour than meets the eye. Dr Matthew Shawkey, an evolutionary biologist at Ghent University in Belgium, said that looking into properties and functions beyond colour’s use for visual means like signalling and camouflage will be critical to understanding its true significance.

‘For example, how do colours affect thermoregulation? Flight? Such functions may be complementary to, or even more significant, than purely visual functions,’ he said.

Dr Shawkey is looking into such questions, with one of his recent studies indicating that the wing colour of birds may play an important role in flight efficiency by leading to different rates of heating.

‘What started as a novelty of deciphering dinosaur colours has turned into a very serious field which is studying the origins of key pigment systems, how the evolution of colourful structures may have helped drive major evolutionary transitions like the origin of flight, and how colour is related to ecology and sexual selection,’ said Dr Steve Brusatte, a vertebrate palaeontologist and evolutionary biologist at the University of Edinburgh, UK.

Ultimately, we may be able to find out more about colour than once thought possible. ‘When I was growing up, so many of the dinosaur books I read in school said that we would never know what colour they were,’ said Dr Brusatte. ‘But as is so often the case in science, it was silly to treat this as impossible.’

He said he is excited to see what comes next, with the field just in its infancy: ‘Palaeontologists now have a whole new window into understanding the biology and evolution of long-extinct organisms.’

Top image: Aline Dassel/Pixabay, licensed under Pixabay licence

The research in this article was funded by the EU. If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.

The article Fossil colour studies are changing our idea of how dinosaurs looked was originally published on Horizon: the EU Research & Innovation magazine | European Commission.