Animating the extinct

This sumptuous video features on our brand new Out of the Deep display and brings to life the two large marine reptile skeletons seen in the cases. The Museum exhibition team worked with Martin Lisec of Mighty Fossils, who specialise in palaeo reconstructions. Martin and his animators also created a longer video explaining how the long-necked plesiosaur became fossilised, as well as beautiful illustrations of life in the Jurassic seas.

Martin explains the process of animating these long-extinct creatures:

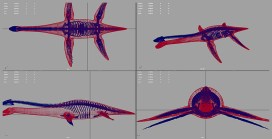

The first step was to make 3D models of all the animals that would appear in the films or illustrations. After discussion with the Museum team, it was clear that we would need two plesiosaurs (one short-necked, known as a pliosaur, one long-necked), ammonites, belemnites and other Jurassic sea life. Now we were able to define the scale of detail, size and texture quality of the model.

In consultation with Dr. Hilary Ketchum, the palaeontologist on the project, we gathered important data, including a detailed description of the discovered skeletons, photographs, 3D scans, and a few sketches.

We created the first version of the model to determine proportions and a body shape. After several discussions with Hilary, some improvements were made and the ‘primal model’ of the long-necked plesiosaur was ready for the final touches – adding details, mapping, and textures. We could then move on to create the other 3D models.

The longer animation was the most time-consuming. We prepared the short storyboard, which was then partly changed during the works, but that is a common part of a creative job. For example, when it was agreed during the process that the video would contain description texts, it affected the speed and length of the whole animation – obviously, it has to be slower so that people are able to watch and read all important information properly.

A certain problem appeared when creating the short, looped animation. The first picture had to precisely follow the last one – quite a difficult goal to reach in case of underwater scenery. Hopefully no-one can spot the join!

At this moment we had a rough animation to be finalised. We had to make colour corrections, add effects and sound – everything had to fit perfectly. After the first version, there were a few more with slight adjustments of animation, cut and text corrections. The final version of both animations was ready and then rendered in different quality and resolution for use in the display and online.

The last part of the project was creating a large illustration, 12,000 x 3,000 pixels, which would be used as a background for a large display panel. Text, diagrams and a screen showing the animations would be placed on this background, making the composition a little tricky. We agreed that the base of the illustration would be just the background. The underwater scene and creatures were placed in separate layers so that it would be easy to adjust them – move them, change their size, position etc.

In the first phase, we had to set the colour scale to achieve the proper look of the warm and shallow sea, then we made rough sketches of the scene including seabed and positions of individual creatures. We had to make continuous adjustments as the display design developed.

Then we finished the seabed with vegetation, gryphaea shells and plankton floating in the water. The final touch was to use lighting to create an illusion of depth for the Jurassic creatures to explore.

*

More Out of the Deep videos are available on the Museum website.

A phylogeny? An evolutionary tree? A cladogram? We see the branching lines of these diagrams in many museum displays and science articles, but what do they tell us and why are they helpful?

A phylogeny? An evolutionary tree? A cladogram? We see the branching lines of these diagrams in many museum displays and science articles, but what do they tell us and why are they helpful?