Art of glass

Spotlight Specimens by Mark Carnall

From the comfort of our own homes, or even on a mobile device, we are accustomed to watching video footage from the most remote environments on Earth, and beyond. It is easy to take for granted this kind of visual access but we don’t have to go too far back in time to reach a point when the uninhabitable parts of the world remained much more mysterious. Then, the only windows into the nature of exotic locations were through drawings, paintings or collected specimens.

In museums, illustrations of nature were – and are – used in teaching to show what certain animals or environments look like. Along with our biological specimens, the Museum’s collections contain representations of animals whose natural appearance is not preserved after death, including a set of beautiful glassworks of British sea anemones.

These delicate models were created by the Blaschkas, a family which specialised in glasswork and ran a business spanning 300 years and nine generations. But it was only from the late 19th century that Leopold Blaschka, later to be joined by his son Rudolf Blaschka, turned his skills to making models of microscopic organisms and soft-bodied invertebrates for museums and universities.

Inspired by zoological specimens, scientific papers, and observation of living animals, as well as artworks showing colours and structures that were difficult to preserve or too small to show, the Blaschkas created thousands of glass models before they accepted a contract in 1886 to work exclusively at Harvard University on the Ware Collection of plant models.

It is somewhat surprising that these incredibly fragile specimens made their way to museums and universities across the globe back in the 19th century and even more surprising that any have survived 150 years later.

Earlier this year the Corning Museum of Glass published an interactive map of marine invertebrate models showing the known locations of collections, or records of collections, of Blaschka glass models.

The models at the Museum, acquired in 1867, are thought to be some of the oldest surviving Blaschka glass models. Even though they are over 150 years old, and in some cases slightly inaccurate representations of species, they still show the vibrant colours and alien shapes of British anemones in a way that can’t be seen outside their living environments.

For Monica in Minerology, I wanted to know more about what people historically considered ‘sympathies’ of gemstones. She directed me to Nichols’ Faithfull Lapidary of 1652, the oldest book in English about the properties of gemstones. The Museum has a copy of the book on loan to the Bodleian, so I’m heading in the direction of that most famous library to get to see the book, perhaps on my next visit.

For Monica in Minerology, I wanted to know more about what people historically considered ‘sympathies’ of gemstones. She directed me to Nichols’ Faithfull Lapidary of 1652, the oldest book in English about the properties of gemstones. The Museum has a copy of the book on loan to the Bodleian, so I’m heading in the direction of that most famous library to get to see the book, perhaps on my next visit.

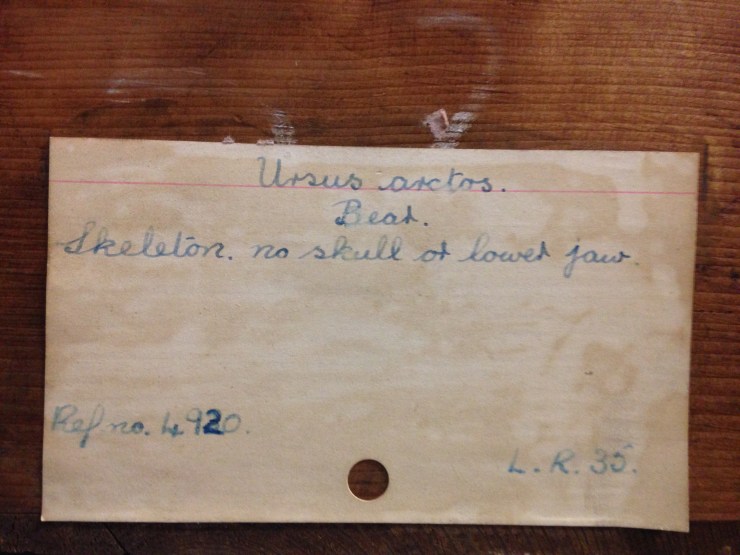

As the new Project Assistant working for the Museum of Natural History, I am the lucky person who gets to discover some of these stories. I will be working with specimens from both Earth and Life collections, as well as some material from the Library and Archives. The first stage will be making a detailed list of everything that needs to be moved, then I can go on to prepare the new store and get the supplies I’ll need to document, pack and transport everything safely.

As the new Project Assistant working for the Museum of Natural History, I am the lucky person who gets to discover some of these stories. I will be working with specimens from both Earth and Life collections, as well as some material from the Library and Archives. The first stage will be making a detailed list of everything that needs to be moved, then I can go on to prepare the new store and get the supplies I’ll need to document, pack and transport everything safely.