The stars our destination?

John Barnie, one of our three Poets in Residence, reflects on claims that the future of life from Earth lies deep in the Solar System…

In a recent article in The New York Review of Books, physicist Freeman Dyson speculates that in three or four hundred years it may be possible to seed promising planets and moons in the solar system with organisms genetically engineered to withstand their harsh conditions, eventually transforming them into environments which could support humans – fleeing, perhaps, from an irreparably damaged Earth.

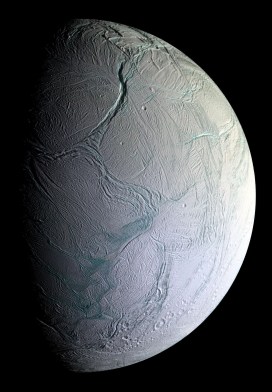

Saturn’s moon Enceladus is one example he gives; geysers pierce its hostile icy surface, and Dyson hypothesises a warm sea hidden below. The process would be achieved by landing ‘pods’ of self-sustaining life forms – ‘Noah’s Arks’ he calls them. The rocket technology is well on its way, he argues, and will be perfected by small cost-effective space companies rather than lumbering giants like NASA. Biotechnology, too, will develop by leaps and bounds to produce, for example, ‘warm-blooded plants’ that would absorb energy – on Saturn’s moon Enceladus, say – concentrated from starlight and the distant rays of the Sun.

In the increasingly stressed and chaotic twenty-first century, it is impossible to predict what will happen in two or three years, let alone two or three hundred. In the meantime, while Professor Dyson elaborates his techno-fantasies, we are here, on the only Ark we have, and the only one, I’d say, we are ever likely to have.

My year at the Museum has been a fascinating and unforgettable reminder of this, the Museum itself forming an ark within an ark, celebrating the extraordinary diversity of multicellular life as it evolved over 650 million years. Many of its specimens, of course, represent extinct species, and they, too, are a reminder – of how life on Earth is fragile but also robust, endlessly reacting and adapting to changing circumstances. Life has survived at least five mass extinctions in the geological record, and will survive the largely human-induced one many biologists and naturalists, from Niles Eldredge to David Attenborough, think we are entering now – though our species may not be around to see what gets through the inevitable extinction bottleneck.

For techno-utopians like Freeman Dyson, the future is out there in space, not here where we evolved, where we have the grounding of our being. The new biotechnology, he argues, will have to be perfected on Earth first, filling ‘empty ecological niches’. They may, he suggests, ‘make Antarctica green before they take root on Mars’. There are so many things wrong with this it is difficult to know where to start. Luckily for us, the Museum of Natural History represents a very different vision of the Earth, its creatures, and our place among them.