Worms of Discovery

By Mark Carnall, Life Collections manager

The Museum’s zoology collections contain a dizzying diversity of animal specimens. It is a collection that would take multiple lifetimes to become familiar with, let alone expert in. So we benefit hugely from the expertise of visiting researchers – scientists, artists, geographers, historians – to name just a few of the types of people who can add valuable context and expand our knowledge about the specimens in our care.

Earlier this year, Dr Andrew McCarthy of Canterbury College (East Kent College Group) got in touch to ask about our material of Acanthocephala, an under-studied group of parasitic animals sometimes called the spiny-headed worms.

Although there are around 1,400 species of acanthocephalans, they are typically under-represented in museum collections. Dr McCarthy combed through the fluid-preserved and microscope slide collections here, examining acanthocephalan specimens for undescribed species, rare representatives and unknown parasitic associations.

One such specimen, catchily referenced OUMNH.ZC.7483, was of particular interest. It is a section of blue whale intestine packed with acanthocephalan adults, labelled ‘Echinorhynchus sp. “Discovery Investigations”’, and dated 13 March 1927. Drawing on his expert knowledge, Dr McCarthy spotted an unusual association here because the genus Echinorhynchus was not known to infect Blue Whales, meaning the specimen could represent a species to new science.

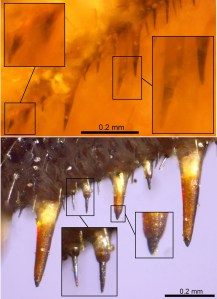

However, identifying different species of acanthocephalans cannot be done by eye alone, so Dr McCarthy requested to remove one of the mystery worms from the intestine and mount it on a slide to examine its detailed anatomy. When we receive a destructive sampling request like this it triggers an investigation of the specimens in question: we need to weigh up their condition, history, and significance against the proposed outcome of the research before we decide whether the permanent alteration of the specimen justifies the outcome.

This particular investigation began to yield a much richer story than the Museum’s label suggested. It turned out that the specimen was collected by Sir Alister C. Hardy who was serving as zoologist on RRS Discovery’s scientific voyage to the Antarctic. Fortunately, Discovery’s scientific findings were meticulously documented and published by many libraries of the world, including the fantastic Biodiversity Heritage Library where it was easy to find the report mentioning acanthocephalans collected during the voyage.

Alongside descriptions of acanthocephalans from seals, dolphins and icefish there is no mention of Echinorhynchus sp. from Blue Whales, though there are a few references to another genus, Bolbosoma, collected from Blue Whales on seven occasions: a single individual of Bolbosoma hamiltoni, so obviously not this specimen, and six occurrences of Bolbosoma brevicolle from the intestines of Blue Whales from South Africa and South Georgia.

Piecing together the evidence, the association with Hardy, the dates, and the descriptions of RRS Discovery’s acanthocephalans, it seems likely that our specimen is one of the six samples of Bolbosoma brevicolle and not Echinorhynchus at all. So in this instance we decided not to grant destructive sampling as the likelihood of identifying a new species seemed much lower when all the information was brought together.

Although sampling wasn’t granted, Dr McCarthy was delighted that his initial research request had prompted the discovery of some important historical connections to the humble specimen, and the new identification seemed to fit.

We still weren’t sure when or why this specimen was mislabelled some time between the Discovery reports and its donation to the Museum in 1949, so Dr McCarthy conducted some further investigations. He found out that Echinorhynchus was the original name combination for Bolbosoma brevicolle, and that H. A. Baylis, a parasitologist and author of Discovery reports, had links with the University of Oxford.

This story is just one example of how visiting researchers enrich knowledge and information about our collections, and it illustrates nicely why our work with broader research communities is so important.