Tales from the Jurassic Coast

Britain’s Jurassic Coast is a famous location for fossil hunters. Dorset’s Lyme Regis in particular was a collecting ground for two very important Victorian palaeontologists – Elizabeth Philpot (1780-1857) and Mary Anning (1799-1847) – and the site yielded some of the earliest specimens of Ichthyosaurs and Plesiosaurs.

Last weekend Channel 4’s Walking Through Time series focused on the Jurassic Coast and featured two members of staff from the Museum, Eliza Howlett and Hilary Ketchum from our Earth Collections. To coincide with the programme, Eliza here delves into the Museum’s Philpot archive to paint a picture of the relationship between Elizabeth Philpot, Mary Anning, and Oxford University’s first Reader in Geology, William Buckland.

*

Elizabeth Philpot moved to Lyme Regis around 1805 with two of her three sisters, Mary and Margaret, where they soon became involved in fossil collecting and where they remained for life. At this time Lyme-born Mary Anning was still a young girl, but so began an affectionate relationship with the Philpot sisters which transcended any barriers of age, social origins or educational background.

As the Philpots’ fossil collection grew it became known in the geological community. One familiar visitor was William Buckland, whose earliest published reference to the ‘Miss Philpots’ is in his 1829 paper on the pterosaur found at Lyme by Mary Anning.

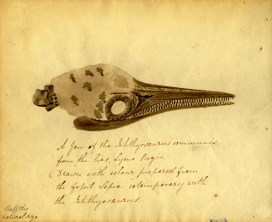

In one letter to Buckland’s wife, Mary, dated 9 December 1833, Elizabeth Philpot enclosed a sketch of an ichthyosaur head that she had painted using ink from a fossil squid of the same age as the ichthyosaur, 200 million years old; this is pictured at the top of the article. The letter also contained a colourful description of Mary Anning’s escapades:

Yesterday [Mary Anning] had one of her miraculous escapes in going to the beach before sun rise and was nearly killed in passing over the bridge by the wheel of a cart which threw her down and crushed her against the wall. Fortunately the cart was stopped in time to allow of her being extricated from her most perilous situation and happily she is not prevented from pursuing her daily employment.

Next, it sends a reminder to William Buckland, a man well-known for forgetting things:

May I beg you to remind Dr. Buckland that he has borrowed from me some Plesiosaurus vertebre. As it is some time since I will mention that it is a section of a vertebre, one with the process, ten others, and a chain set in a box.

These letters from Elizabeth Philpot are now held by the Museum, along with the Philpot collection of around 400 fossils. Mostly from Lyme Regis, this collection includes more than 40 type specimens, the reference specimen for a new species, which is a remarkable total for any collector. A brief list of people known to have examined the collection is practically a roll call of the key figures in 19th-century palaeontology: William Buckland, William Conybeare, John Lindley and William Hutton, Richard Owen, James Sowerby, and (from Switzerland) Louis Agassiz.

But the collection was also made available to the ordinary people of Lyme, and the handwritten labels by Elizabeth Philpot sometimes included detailed explanations of what these extinct animals would have looked like. Both the letters and the specimens remain deeply evocative today, conjuring up visions of what it must have been like to call on these three remarkable sisters.

Because of the risk of light damage the material is not normally on display, but it can be viewed by appointment. Email library@oum.ox.ac.uk or earth@oum.ox.ac.uk for more information.

You’ve read about it in the

You’ve read about it in the