High time for a check up

by Bethany Palumbo, life collections conservator

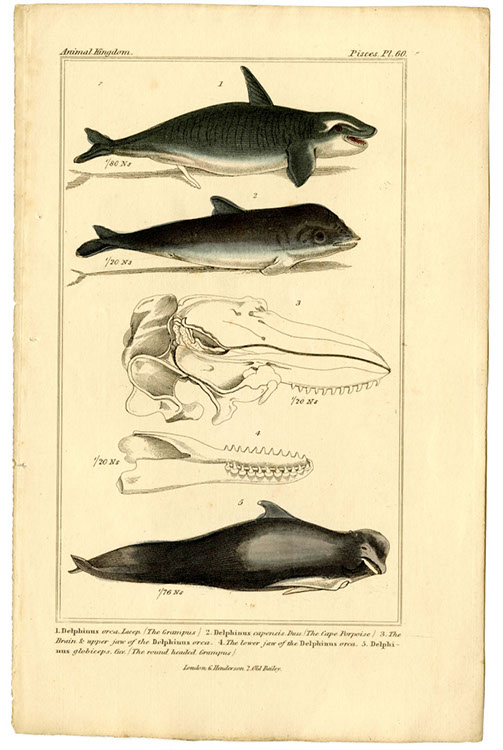

This month marks three years since the completion of our ‘Once in a Whale’ project. The initial conservation undertaken in 2013 focused on the cleaning and stabilisation of five whale skeletons, which had hung from the roof of the Museum for over 100 years.

The skeletons were lowered into a special conservation space, where the team were able to work up close with the specimens. As well as the cleaning, they improved incorrect skeletal anatomy, replacing old corroded wiring with new stainless steel. For final display, the specimens were put into size order and rigged using new steel wiring, with the larger specimens being lifted higher into the roof space to make them a more prominent display than previously. You can read all about the project on our blog, Once in a Whale.

Three years on, our conservation team felt it was a good time to check on the specimens to see how they’re coping, post-treatment, in the fluctuating museum environment.

It’s been wonderful to see the whales on display and their new position looks very impressive. However, when the time came for making this recent conservation assessment, the new height was greater than any of our ladders could reach. Specialist scaffolding was brought in to allow the conservators to access the specimens. Starting at the highest level, with our Beaked Whale, cleaning was completed using a vacuum and soft brush for delicate areas. This removed a thick layer of dust and particulate debris: especially satisfying work!

With cleaning complete, visual assessments could then be undertaken. These showed that while the specimens were still very stable, a few areas of bone have continued to deteriorate, visible in cracking and flaking of the surface. In other areas, the fatty secretions which we previously removed using ammonia had once again started to emerge. We had expected to see this though, because, in life these whales’ bodies contained a lot of fat, deep within the bones and this is notoriously impossible to completely remove.

It was also observed that the lubrication used on the new rigging bolts had melted and dripped down the wires. You can see in the photo above how this has become drawn into the vertebrae of the Orca and Common Dolphin, staining them yellow. While no conservation treatment was undertaken due to time restrictions, thorough photography was performed to document these changes and once time permits this can be carried out.

This shows how conservation work, especially with natural history specimens, is a gradual, ongoing process. With frequent check-ups and specialist attention, these whales will be able to continue their life as our beautiful display specimens.