Movers and settlers

Our new exhibition Settlers, which opens today, shows that the history of the people of Britain is one of movement, migration and settlement. Here, exhibition writer Georgina Ferry finds that Britain has been receiving new arrivals since the last Ice Age.

In Britain following the Brexit vote, the word ‘migration’ has taken on an emotional and political charge. A new exhibition opening today takes a long-view of the movement of people, looking in particular at how migration has formed the British population.

Settlers: genetics, geography and the peopling of Britain tells the story of the occupation of Britain since the end of the last Ice Age, about 11,600 years ago. From this perspective, today’s pattern of movement into and out of the country is only the latest in a long history of alternating change and stability that has made the people of Britain who they are today.

About 340,000 – 300,000 years ago, when conditions were slightly warmer than at present, Neanderthal hunters lived alongside a channel of the Thames near Oxford where the village of Wolvercote now stands. They made flint hand axes – all-purpose butchering, digging and chopping tools. They hunted animals now extinct in Britain.

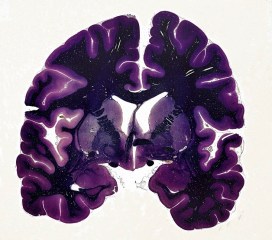

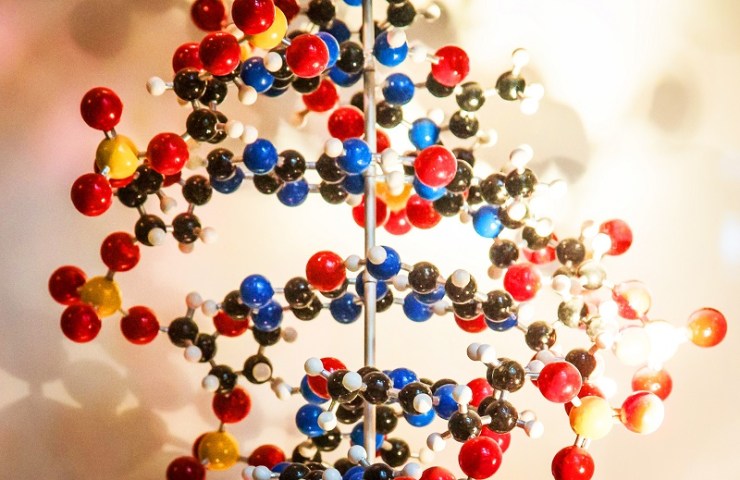

Tracing these movements has been a fascinating detective story, with clues coming from many different types of evidence. The starting point for Settlers is a remarkable study carried out by Oxford scientists, who used DNA samples from contemporary British volunteers to trace the origins of the people who settled Britain between the end of the Ice Age and the Norman Conquest of 1066. One striking finding is that the bonds that unite Celtic communities in Cornwall, Wales and Scotland are largely cultural – genetically these groups are quite distinct.

The genetic evidence adds a new dimension to the archaeological story, based on artefacts left behind by our ancestors, or other historical signposts such as place names. For example, although occupying Roman armies left us the names of their forts and cities, they don’t seem to have left much of their DNA. They came, saw and conquered, but didn’t stay in large enough numbers to make a genetic impact on the native British population. In contrast the Anglo-Saxons, who arrived after the Romans withdrew, left a strong genetic signature everywhere except Wales and the Scottish Highlands.

It took 2,000 volunteers and software that can distinguish tiny differences to arrive at the various regional clusters that came out of the study. When you visit the exhibition, you can play a fascinating interactive lottery game to see just how unlikely it is that genes from any specific ancestor of more than a few generations will still be in your DNA.

The story of movement and settlement doesn’t stop in 1066. Researchers in Oxford’s School of Geography have plotted census data since 1841 against global events, from the persecution of Russian Jews to the enlargement of the European Union, to illustrate the ebb and flow of people from and to Britain that has produced the current population mix. Another interactive lets you compare your own family’s journey with those of all the other visitors.

We will have to wait until the census of 2021 to know what a difference Brexit will make, but we can be sure that people will be arriving and leaving for a lot longer than that.