By Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente, Museum Research Fellow

One of the earliest and toughest trials that all organisms face is birth. In egg-laying animals, the egg shell that has protected the embryo during its early development ultimately becomes a hard barrier between the animal and its life out in the world. The bursting of the egg is literally a threshold moment, and there are many ways to crack an egg…

Some animals break the egg membranes using dissolving chemicals; others physically, mechanically tear their way through the shells. Among the latter, a great diversity of animals use specialised devices called egg bursters. These vary greatly among the many arthropods and vertebrates that use them, but perhaps the most famous example is the ‘egg tooth’ that is present on the beak of newborn chicks.

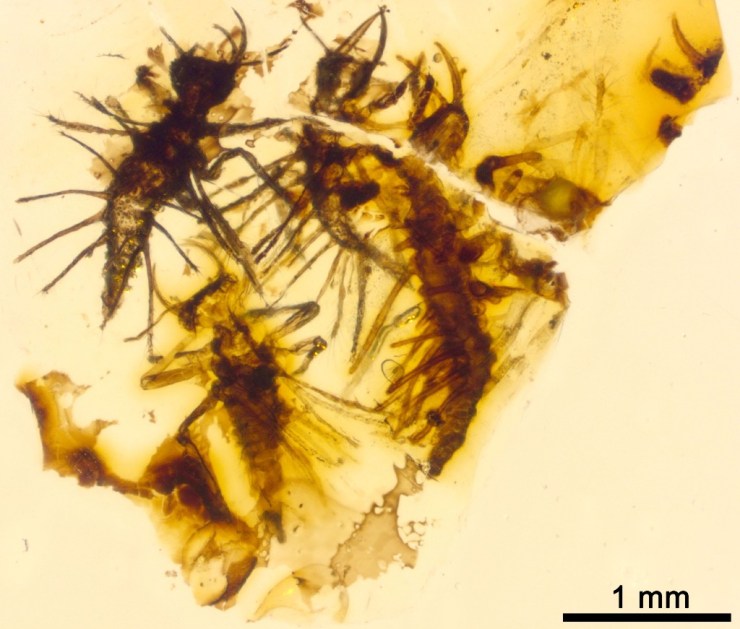

My colleagues and I have found an exceptional fossil in 130 million-year-old Lebanese amber. Inside, trapped together are newborn larvae from Green Lacewings, the split egg shells from where they hatched, and the minute egg bursters that the hatchlings used to crack the egg. This is a first: no definitive evidence of these specialised egg-bursting structures had been reported from the fossil record of any egg-laying animals, until now.

The finding has been recently published as open access in the journal Palaeontology. Because multiple newborns were ensnared and entombed in the resin simultaneously, the fossil larvae have been described as the new species Tragichrysa ovoruptora, meaning ‘tragic green lacewing’ and ‘egg breaking’. A sad event, indeed, taking place in an ordinary day 130 million years ago in the Cretaceous forests of Lebanon, yet a happy circumstance now that we can take a privileged glimpse into the adaptations and behaviours of these fascinating tiny creatures.

The hatchlings from modern Green Lacewings open a slit on the egg with a ‘mask’ bearing a saw-like blade. Once used, this ‘mask’ is shed together with the embryonic cuticle and is left attached to the empty egg shell.

With the help of Amoret Spooner, Collections Manager at the Museum, egg clutches from modern green lacewings were found in the Museum collections. These eggs happened to have the intact egg bursters still attached to them, and proved to be crucial to understand that we had the same structures preserved in the amber together with the newborn larvae.

Green Lacewing larvae are small predators that often carry debris as camouflage, using their sickle-shaped jaws to pierce and suck the fluids of their prey. Whereas the larvae trapped in amber differ significantly from modern-day relatives, in that they possess long tubes instead of clubs or bumps for holding debris, the studied egg shells and egg bursters are remarkably similar to those of today’s green lacewings.

The larvae were almost certainly trapped by resin while clutching the eggs from which they had freshly emerged. Such behaviour is common among modern relatives while their body hardens and their predatory jaws become functional. Indeed, the two mouthparts forming the jaws are not assembled in most of the fossil larvae, which indicates, together with the large relative size of the head and legs, that they were recently born.

It may seem reasonable to assume that traits controlling a life event as decisive as hatching would have remained largely unchanged during evolution. In fact, we see in very closely related insect groups different means of hatching that can entail the loss of the egg bursters. So the persistence of a hatching mechanism in a given animal lineage through deep time can’t be determined without direct proof from the fossil record.

This new discovery shows that the mechanism green lacewings use to crack the egg was already established 130 million years ago. Overall, it represents the first direct evidence of how insects hatched in deep time, egg-bursting their way through into life.

*

The hatching mechanism of 130-million-year-old insects: an association of neonates, egg shells and egg bursters in Lebanese amber by Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente, Michael S. Engel, Dany Azar and Enrique Peñalver is published as open access in Palaeontology this month.

Published by