Is it real? – Fossils

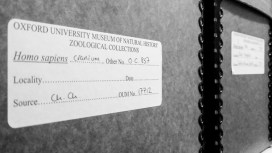

One of the most common questions asked about our specimens, from visitors of all ages, is ‘Is it real?’. This seemingly simple question is actually many questions in one and hides a complexity of answers.

In this FAQ mini-series we’ll unpack the ‘Is it real?’ conundrum by looking at different types of natural history specimens in turn. We’ll ask ‘Is it a real animal?’, ‘Is it real biological remains?’, ‘Is it a model?’ and many more reality-check questions.

This time: Fossils, by Duncan Murdock

Whether it’s the toothy grin of a dinosaur towering over you, an oyster shell in the paving stone beneath you, or a trilobite in your hand, fossils put the prehistory into natural history collections. Anyone who has spent a day combing beaches for ammonites, or scrabbling over rocks in a quarry will attest that fossils are ‘real’. It is the thrill of being the only person to have ever set eyes on an ancient creature that drives us fossil hounds back to rainy outcrops and dusty scree slopes. But fossils, unlike taxidermy and recent skeletons, very rarely contain any original material from living animals, so are they really ‘real’?

Fossils are remains or traces of life (animals, plants and even microbes) preserved in the rock record by ‘fossilisation’.

This chemical and physical alteration makes fossils stable over very long timescales, from the most ancient glimpses of the first microbes billions of years ago to sub-fossils of dodos, mammoths and even early humans just a few thousand years old. They can be so tiny they can only be seen with the most high-powered microscopes or so huge they can only be displayed in vast exhibition halls, like our own T. rex. Among this is a spectrum of how much of the ‘real’ animal is preserved, and how much preparation and reconstruction is required to be able to display them in museums.

Generally, the more there is of the original material and anatomy, the rarer the fossils are. Among the most common fossils found are ‘trace fossils’: burrows, footprints, traces, nests, stomach contents and even droppings (known as ‘coprolites’). Most ‘body’ fossils also contain nothing of the living creature, rather they are impressions of hard parts like teeth, bones and shells.

When an organism is buried the soft parts quickly decay away. The hard parts decay much more slowly, and can leave space behind, creating a fossil mould. If this later gets filled with different sediment, it forms a cast.

These sediments are buried further still and eventually turned into rocks. Alternatively, the hard parts can be replaced by different minerals that are much more stable over geological time. Essentially bone becomes rock one crystal at a time.

Very rarely the soft parts of an organism get preserved, but in the most exceptional cases skin, muscles, guts, eyes and even brains can be preserved. If buried quickly enough an animal can be compressed completely flat to leave behind a thin film of organic material, or even soft parts themselves can be replaced by minerals, piece-by-piece. These mineralized fossils can be exquisitely preserved in three dimensions, even down to individual cells in some cases. This is about as ‘real’ as most fossils can be, except the few special cases where the remains of an organism are preserved virtually unaltered, entombed in amber, sunk into tar pits or bogs, or frozen in permafrost. The latter push the boundaries of what can really be called a fossil.

The final step in the process, from the unfortunate demise of a critter to its eventual study or display, involves preparation. In most cases the fossil has to be removed from the surrounding rock with hammers, chisels, dental tools and sometimes acids. This preparation can be quite subjective, a highly skilled preparator has to make judgements about what is or isn’t part of the fossil. The specimen may also need to be glued together or cracks filled in, so not everything you see is always original.

As with modern skeletons, there are often missing parts, so a fully articulated dinosaur skeleton may be a composite of several individuals, or contain replica bones. This is, of course, not a problem as long as it is clear what has been done to the fossil. This is not always the case, and there are examples of deliberately forged fossils, carved into or glued onto real rocks, or forgeries composed of several different fossils to make something ‘new’, like a ‘cut n shut’ car.

So, if you see a fossil that looks too good to be true, then it just might be worth asking, “is it real”?

Next time… Models, casts and replicas

Last time… Skeletons and bones

There were massive cracks inside the mouth, where the old fill material had failed. After some testing, I chose a fill material that was flexible and able to withstand a fluctuating museum environment. This was an EVA adhesive, coloured with pigments to match the surrounding gum.

There were massive cracks inside the mouth, where the old fill material had failed. After some testing, I chose a fill material that was flexible and able to withstand a fluctuating museum environment. This was an EVA adhesive, coloured with pigments to match the surrounding gum.

The panel for this debate includes world experts in the fields of neuroethics, evolutionary psychology, and philosophy, each representing different sides of this challenging subject.

The panel for this debate includes world experts in the fields of neuroethics, evolutionary psychology, and philosophy, each representing different sides of this challenging subject.

![Par Samuel Garman (1843-1927) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://morethanadodo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/telmatobius_culeus.jpg?w=740&h=792)

![By Charlesjsharp (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://morethanadodo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/800px-male_galc3a1pagos_greater_frigate_bird.jpg?w=740&h=438)

![By User:Cacophony [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://morethanadodo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/1024px-sturgeon.jpg?w=740&h=408)

![By Pengo (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://morethanadodo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/800px-hoplostethus_atlanticus_02_pengo.jpg?w=740&h=318)

![By Raul654 (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://morethanadodo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/885px-okapi2.jpg?w=740&h=642)