A moving story

For the past nine months there has been a lot of moving going on around here. Imagine moving house endlessly for weeks on end, but where your house is full of bones, insects, fossils, rocks, and weird and wonderful taxidermy. And the location of everything has to be precisely recorded. The museum move project was a bit like that.

Project assistant Hannah Allum explains…

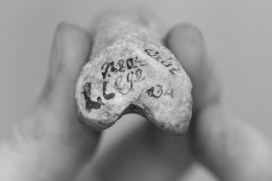

The museums are migrating, we declared in May 2016. And so they have. The first major stage of the stores project has been completed. After we had created inventories for the largely unknown collections held in two offsite stores, the next stage was to pack them safely and transport them to a new home nearer the museum, a job which demanded almost 70 individual van trips! We now have over 15,000 specimens sitting in vastly improved storage conditions in a new facility.

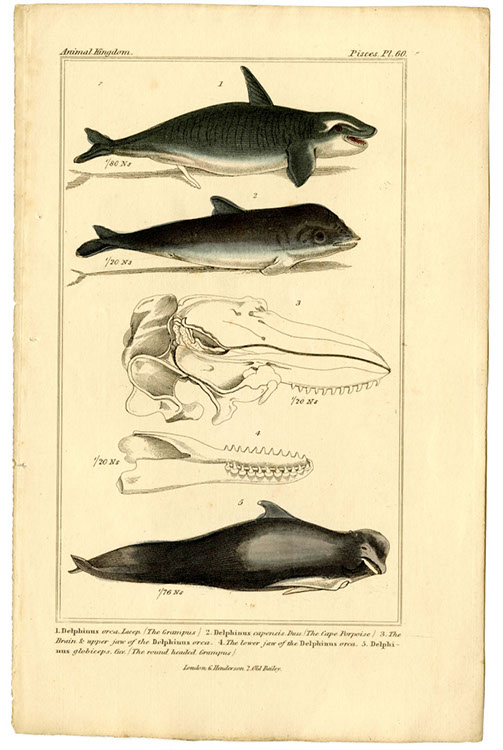

Let’s revel in some numbers. All in all there were over 1,000 boxes of archive material, mostly reprints of earth sciences and entomological research papers; over 1,300 specimens of mammal osteology (bones); and more than 1,000 boxes and 650 drawers of petrological and palaeontological material (rocks and fossils).

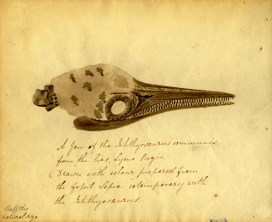

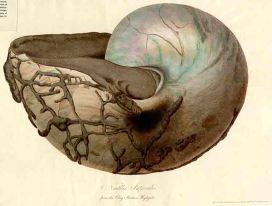

Some of the more memorable specimens include old tobacco tins and chocolate boxes filled with fossils and shells; a beautifully illustrated copy of the ‘Report on the Deep-Sea Keratosa’ from the HMS Challenger by German naturalist Ernst Haeckel; and the skull of a Brazilian Three-banded Armadillo (Tolypeutes tricinctus), complete with armour-plated scute carapace.

There were also a few objects that have moved on to more unusual homes. A 4.5 m long cast of Attenborosaurus conybeari (yep, named after Sir David) was too large to fit in our new store and so made its way to another facility along with a cornucopia of old museum furniture. A set of dinosaur footprint casts, identical to those on the Museum’s lawn, have been gifted to the Botanical Gardens for use at the Harcourt Arboretum in Oxford.

And last but not least, a model of a Utahraptor received a whopping 200 applications from prospective owners in our bid to find it a suitable home. After a difficult shortlisting process it was offered to the John Radcliffe Children’s Hospital and following a quarantine period should soon be on display in their West Wing.

Fittingly, the final specimen I placed on the shelf in the new store was the very same one that had been part of my interview for this job: The skeleton of a female leopard with a sad story. It apparently belonged to William Batty’s circus and died of birthing complications whilst in labour to a litter of lion-leopard hybrids before ending up in the Museum’s collections in 1860.

Though the moving part of this project is now complete there is still plenty of work to do. We are now updating and improving a lot of the documentation held in our databases, and conservation work is ongoing. The new store will also become a shared space – the first joint collections store for the University Museums, complete by April 2018.

To see more, follow the hashtag #storiesfromthestores on Twitter @morethanadodo and see what the team at Pitt Rivers Museum are up to by following @Pitt_Stores.