An Eye for a Pattern

Fifty years ago this month the Royal Swedish Academy announced that Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin had won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. She remains the only British woman scientist ever to win a Nobel Prize.

The Museum celebrated Hodgkin’s achievement with a bust in the Court – the only female face among all the statues looking down on the dinosaurs. Although the bust is currently off display, undergoing conservation work, she deserves her place more than anyone: she first learned the skills of X-ray crystallography in the Museum, and carried out all of her Nobel Prizewinning work there.

Georgina Ferry, author of Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life, and a former author in residence at the Museum, reveals more about Dorothy’s work.

*

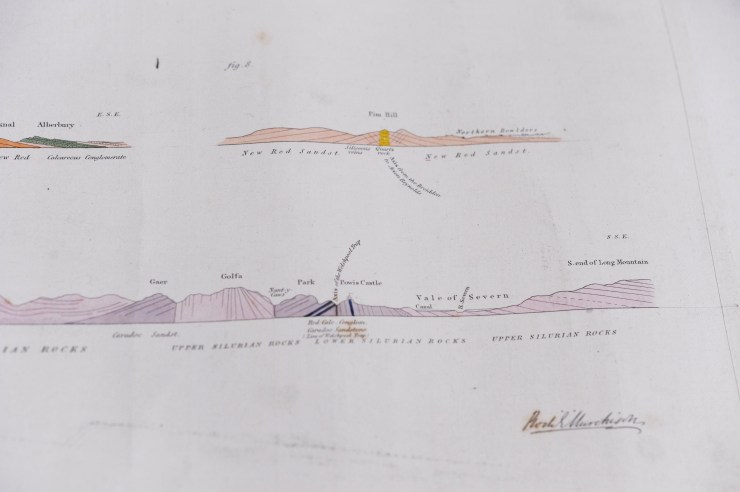

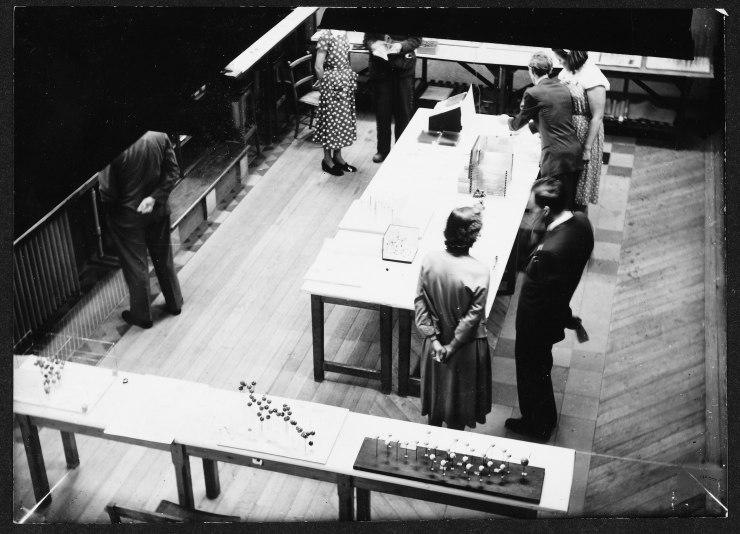

In 1928, when Dorothy Crowfoot (as she then was) arrived in Oxford to study chemistry, the Museum was still the centre of teaching and research in several science subjects including crystallography. The following year the department installed the equipment needed for X-ray work. Dorothy chose to do her Part II research project in X-ray crystallography, the first student to do so. From photographs of the patterns of spots generated by firing beams of X-rays through tiny crystals, she could calculate the positions of the atoms inside the crystal, and so understand how its structure influenced its chemical role.

At the time the whole Mineralogy and Crystallography Department worked and taught in the room under the tower where Samuel Wilberforce and Thomas Huxley conducted their famous debate on human evolution in 1860. There was a darkroom suspended from the ceiling for examining crystals, another curtained-off area for developing photographs, and the X-ray tube, connected to an alarmingly unsafe power supply, sat on a table in the corner.

After getting a first class degree in 1932, Dorothy went to Cambridge to do a PhD with JD Bernal. There she began to study biologically important substances such as cholesterol and pepsin.

After getting a first class degree in 1932, Dorothy went to Cambridge to do a PhD with JD Bernal. There she began to study biologically important substances such as cholesterol and pepsin.

Two years later she was back in Oxford with a fellowship at Somerville. She started her own research in a dingy semi-basement in the northwest corner of the Museum. That remained her lab for more than 20 years. It was there that she solved the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in crystals of penicillin and Vitamin B12, the achievements that won her the Nobel Prize.

All through this week, as the Nobel Prizes for 2014 are being announced, you can hear Dorothy’s life story told through her letters on BBC Radio 4, in the series An Eye for Pattern (it will be on iPlayer thereafter if you missed it).

With thanks to the Bodleian Library and the Department of Chemistry,University of Oxford for the use of the photographs.

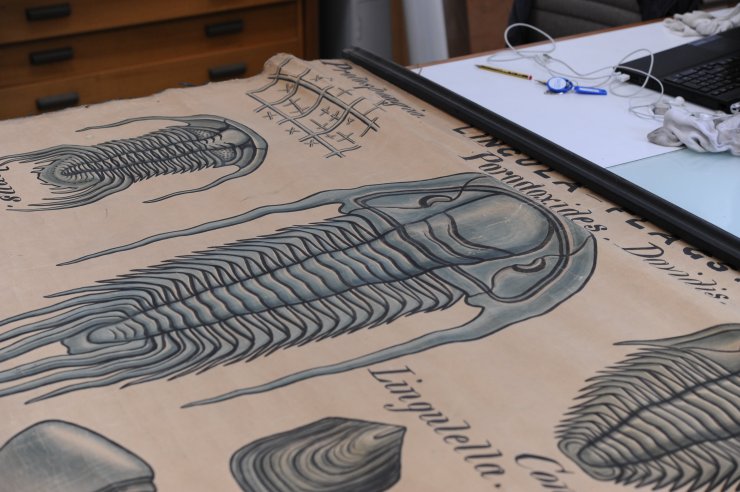

In rush hour traffic, carrying a precious cargo, the Museum’s Director, Professor Paul Smith and Head of Archival Collections, Kate Santry, headed north. They took the William Smith archive on tour to the Yorkshire Fossil Festival, in lovely Scarborough. Hosted by the

In rush hour traffic, carrying a precious cargo, the Museum’s Director, Professor Paul Smith and Head of Archival Collections, Kate Santry, headed north. They took the William Smith archive on tour to the Yorkshire Fossil Festival, in lovely Scarborough. Hosted by the