Ruskin 200 Art Competition

By Michelle Alcock, Front of House Deputy Manager

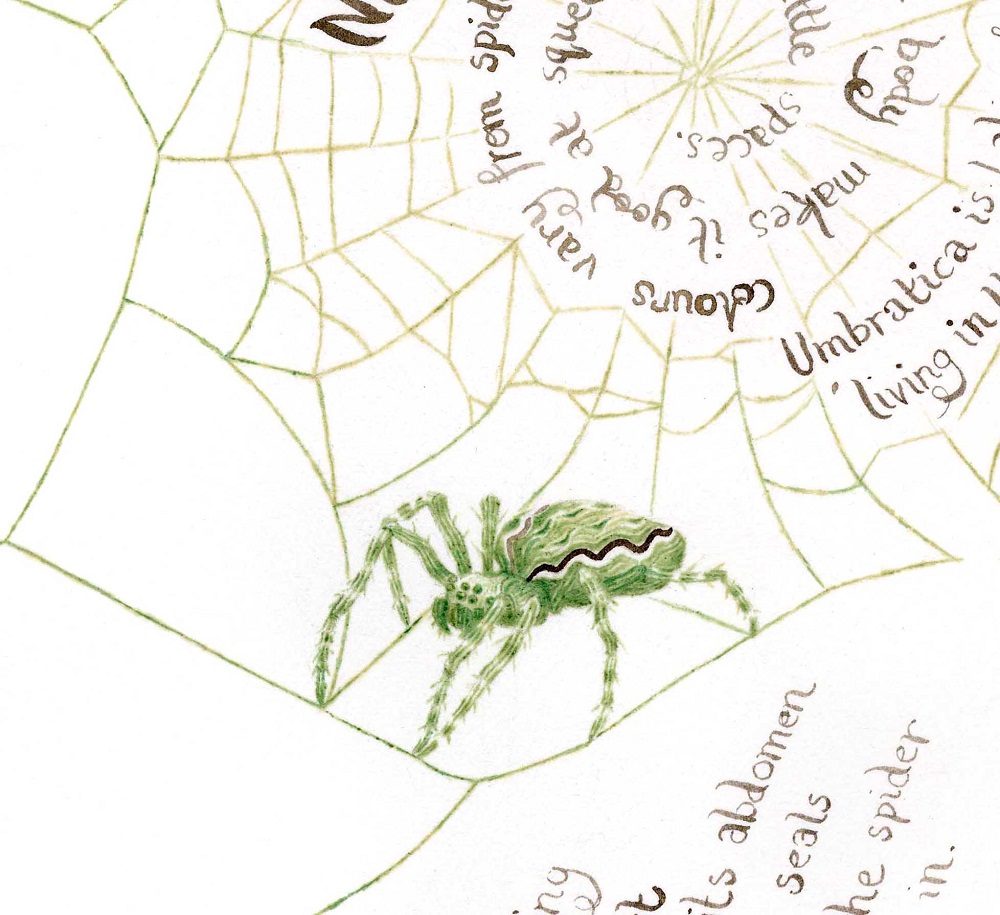

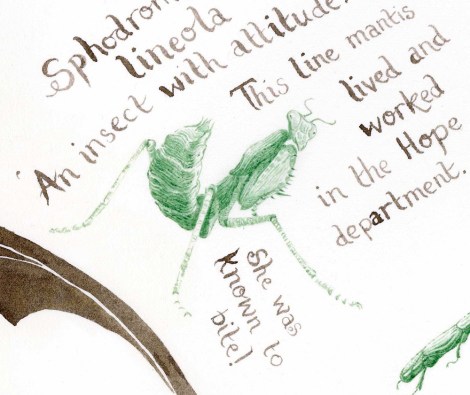

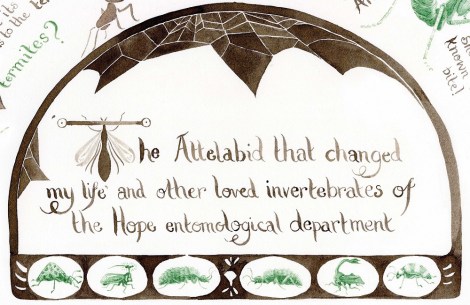

To celebrate the Museum of Natural History and the creativity it inspires, we have launched the Ruskin 200 Art Competition. It opened on Friday 8 February 2019 coinciding with the bicentenary of the birth of John Ruskin; an artist, social thinker, philanthropist and art critic of the 19th century. During the Victorian era, Ruskin’s views advocating for drawing from direct observation, both in his studies of Gothic architecture, and in his use of a detailed descriptive approach to depict nature in art, heavily influenced the design of the Museum.

Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

His encouragement led to artists, architects, craftsmen and scientists working together to design the Museum. As a result, they created the neo-Gothic building that stands today as a work of art and a vision of nature in its own right. The Museum’s architecture, decorative details, and collections have served as a source of inspiration for many since it opened in 1860.

This year marks the perfect opportunity to showcase the artwork of our visitors. Personally, working on the Front of House team here, I see what an inspiration the building is to our visitors. Every day we spot people of all ages setting up stools, with pencil and sketchbook at the ready, drawing in the Museum. There is so much potential inspiration; beetles carved in stone, vibrant birds’ feathers, glittering gemstones and the intricate decorative ironwork of the building, to name a few.

It is always exciting to see so many of our visitors engaging with the Museum in a creative way, but we rarely see the finished product. I’ve always wanted to know what artwork is created from this point of inspiration. Is it the starting point of a vibrant painting, an intricate pastel drawing or a graphic mixed media collage? The list of possibilities is endless.

Whatever your choice of creative expression, we want to see your interpretation of the Museum and what inspired you, whether it’s the architecture or the collections on display. If you are an amateur or professional artist, and over the age of sixteen, we would like you to submit your artwork to the Ruskin 200 Art Competition.

The competition is open for four months. Do send us images of your final artwork before the closing date of 19 May 2019. Selected artworks from each of the four entry categories will go on display in the Museum during the busy summer holidays.

Throughout 2019, we’re also running a programme of drawing activities to celebrate Ruskin’s bicentenary. It began with the Ruskin Drawing Weekend on 9 and 10 February, which included lots of different activities to begin the creative process. Look out for our Ready, Steady, Draw! workshops for younger artists coming in May too.

The full competition guidelines, along with further information on the Ruskin-related events we’re running this year, can be found on our website.

Top banner image: WA1931.47 John Ruskin, Design for a Window in the University Museum, Oxford. Image copyright Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford