Bound by blood

It may sound like we’ve stumbled into a script-writing session for Jurassic Park, but one of our research fellows, Dr Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente, along with an international team, has discovered a parasite trapped in amber, clutching the feather of a dinosaur. This small fossilised tick, along with a few other specimens, is the first direct evidence that ticks sucked the blood of feathered dinosaurs 100 million years ago. Ricardo tells us all about it…

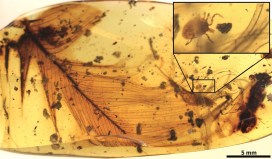

The paper that my colleagues and I have just published provides evidence that ticks fed from feathered dinosaurs about 100 million years ago, during the mid-Cretaceous period. It is based on evidence from amber fossils, including that of a hard tick grasping a dinosaur feather preserved in 99 million-year-old Burmese amber.

The probability of the tick and feather becoming so tightly associated and co-preserved in resin by chance is virtually zero, which means the discovery is the first direct evidence of a parasite-host relationship between ticks and feathered dinosaurs.

Fossils of parasitic, blood-feeding creatures directly associated with remains of their host are exceedingly scarce, and this new specimen is the oldest known to date. The tick is an immature specimen of Cornupalpatum burmanicum; look closely under the microscope and you can see tiny teeth in the mouthparts that are used to create a hole and fix to the host’s skin to suck its blood.

The structure of the feather inside the amber is similar to modern-day bird feathers, but it could not belong to a modern bird because, according to current evidence at least, they did not appear until 26 million years later than the age of the amber.

Feathers with the same characteristics were already present in multiple forms of theropod dinosaurs – the lineage of dinosaurs leading to modern birds – from ground-runners without flying ability, to bird-like forms capable of powered flight. Unfortunately, this means it is not possible to determine exactly which kind of feathered dinosaur the amber feather belonged to.

But there is more evidence of the dinosaur-tick relationship in the scientific paper. We also describe a new group of extinct ticks, created from a species we have named Deinocroton draculi, or “Dracula’s terrible tick”. These novel ticks, in the family Deinocrotonidae, are distinguished from other ticks by the structure of their body surface, palps and legs, and the position of their head, among other characteristics.

This new species was also found sealed inside Burmese amber, with one specimen remarkably engorged with blood, increasing its volume approximately eight times over non-engorged forms. Despite this, it has not been possible to directly determine its host animal:

Assessing the composition of the blood meal inside the bloated tick is not feasible because, unfortunately, the tick did not become fully immersed in resin and so its contents were altered by mineral deposition.

Dr Xavier Delclòs, an author of the study from the University of Barcelona and IRBio.

But there was indirect evidence of the likely host for these novel ticks in the form of hair-like structures called setae from the larvae of skin beetles, or dermestids, found attached to two Deinocroton ticks preserved together. Today, skin beetles feed in nests, consuming feathers, skin and hair from the nest’s occupants. But as no mammal hairs have yet been found in Cretaceous amber, the presence of skin beetle setae on the two Deinocroton draculi ticks suggests that their host was in fact a feathered dinosaur.

Together, these findings tell us a fascinating story about ancient tick behaviour. They reveal some of the ecological interactions taking place among early ticks and birds, showing that their parasite-host relationship has lasted for at least 99 million years: an enduring connection, bound by blood.

The paper “Ticks parasitised feathered dinosaurs as revealed by Cretaceous amber assemblages” is published as open access in Nature Communications. Direct link: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01550-z