Lynn Margulis and the origins of multicellular life

To mark International Women’s Day Professor Judith Armitage, lead scientist on the Bacterial World exhibition, reflects on the ground-breaking – and controversial – work of evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis

Iconoclastic, vivacious, intuitive, gregarious, insatiably and omnivorously curious, partisan, bighearted, fiercely protective of friends and family, mischievous, and a passionate advocate of the small and overlooked.

These are all words used to describe evolutionary biologist and public intellectual Lynn Margulis. Intellectually precocious, Margulis got her first degree from the University of Chicago aged 19, but it was her exposure to an idea about the evolution of a certain type of cell that ignited a lifelong focus of her work.

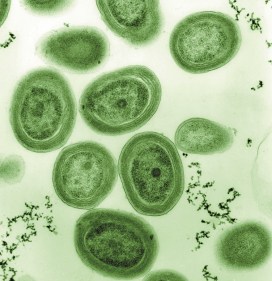

This idea claimed that eukaryotic cells – cells with a nucleus, found in all plants and animals, but not bacteria – were first formed billions of years ago when one single-celled organism – a prokaryote – engulfed another to create a new type of cell. This theory, known as endosymbiosis, was laid down in a paper by Margulis in 1967. It brought her into conflict with others, including the so-called neo-Darwinists who believed in slow step-wise evolution driven by competition between organisms, not cooperation.

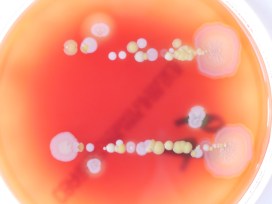

So what happened in the earliest evolution of these crucial cells? Initially, one bacterium ate a different, oxygen-using bacterium but didn’t digest it. Over time the two became interdependent and the bacterium took over almost all of the energy-generating processes of the host cell, becoming what we now call a mitochondrion. This allowed the cell to evolve into bigger cells and eventually form communities and develop into multicellular organisms.

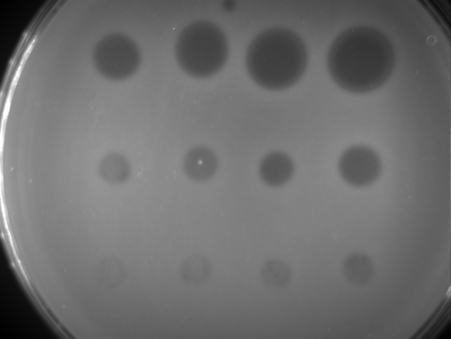

These early mitochondria-containing organisms continued to eat other bacteria, and on more than one occasion they ate a photosynthesising cyanobacterium which evolved into a chloroplast, a structure now found inside plant cells.

The revolution in DNA sequencing that started in the 1970s, and continues today, eventually vindicated Margulis’ position on this ancient sequence of events. It revealed that chloroplasts and mitochondria both contain DNA with the same ancestry as cyanobacteria and proteobacteria respectively. In other words, both chloroplasts and mitochondria have evolved from ancient bacteria.

Margulis’ enthusiastic support for these ideas led her to think about the role of biology in the geology of Earth and some of its major changes, in particular the oxygenation of the atmosphere by cyanobacteria around 2.5 billion years ago. Mitochondria use oxygen, and so must have evolved from bacterial ancestors that arose after the cyanobacteria started to produce oxygen through photosynthesis.

Margulis met Gaia theorist James Lovelock soon after her seminal publication on endosymbiosis. At the time, Lovelock was looking at the composition of the atmosphere and factors causing change, including oxygen levels. He was starting to think of the Earth as a system – Gaia as it became known – where the planetary environment is regulated and kept stable by biological activity.

This meeting brought together two scientific outliers. Together they produced highly controversial articles on the “atmosphere as a biological contrivance”. Lovelock believed in concentrating on examining the systems as they are now, while Margulis brought deep time and evolutionary depth into the picture.

Margulis’ ideas were not always right, and she was enormously controversial in her time, but she made people think again. And in doing so she moved our understanding of things as apparently academically distant as the evolution of tiny cells billions of years ago to the stability of Earth’s environment today.

Top image: Euglena, a single cell eukaryotic. By Deuterostome [CC BY-SA 3.0]