Nature’s Waste Management Team

A Spotlight Specimens special for Oxford Festival of Nature

By Darren Mann, Head of Life Collections

One cow can produce over nine tonnes of dung per year. With a population of about 3.4 million cows in the UK alone, that’s a heck of a lot of dung deposited on our grasslands. Just imagine how much dung is produced every year if we include the output of horses, sheep, pigs, and all the wild animals out there.

All of this dung is broken down by a multitude of invertebrates, including flies, worms, and beetles, as well as bacteria, fungi, and weathering. One of the key groups involved in the removal and degradation process is the aptly named ‘dung beetles’.

In the UK there are 61 species of dung beetle, though sadly just over half of these are now in decline and some have already become regionally extinct. UK dung beetles vary in size from just 3 mm to over 25 mm and occur wherever dung is found, though some prefer sandy soils and others like to live in woodlands.

As adults, dung beetles feed on the liquid part of dung. The larvae of most of our species live inside the dung pile and are called the dwellers. These munch their way through the solid matter of the dung pile, gradually breaking it down over a few months. Other species such as Geotrupes mutator, pictured above, excavate a tunnel and bury the dung below ground. These tunnellers construct a brood chamber in which their young develop.

Through their actions, dung beetles perform a number of valuable ecosystem services. The most obvious is dung removal and degradation which leads to improved soil health by nutrient cycling and soil movement. By burying the dung they reduce the amount of available breeding habitat for pest flies and livestock parasites too.

All of these important services have been estimated to save the UK cattle industry £367 million per year. The value of dung beetles doesn’t end there as they also provide an important source of food for farmland mammals and birds. So next time you see a pile of dung in a field, just think of all the hard working beetles within…

Staff and associates of the Museum also run the Dung beetle UK Mapping Project – affectionately abbreviated to DUMP!

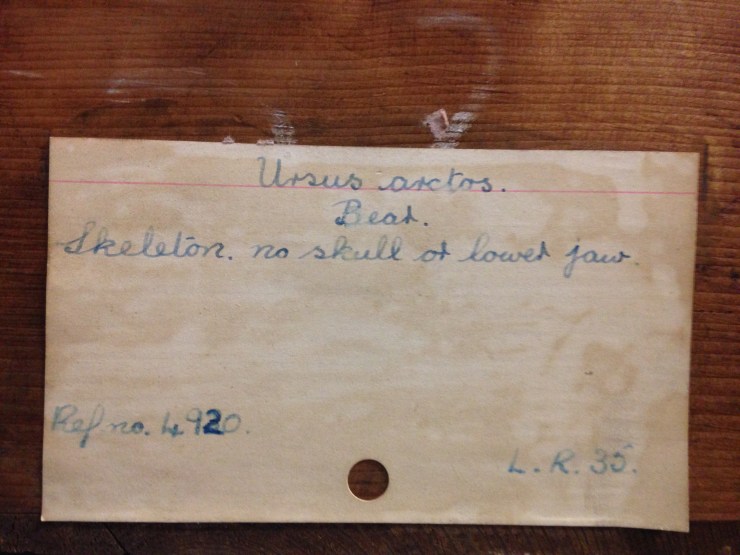

As the new Project Assistant working for the Museum of Natural History, I am the lucky person who gets to discover some of these stories. I will be working with specimens from both Earth and Life collections, as well as some material from the Library and Archives. The first stage will be making a detailed list of everything that needs to be moved, then I can go on to prepare the new store and get the supplies I’ll need to document, pack and transport everything safely.

As the new Project Assistant working for the Museum of Natural History, I am the lucky person who gets to discover some of these stories. I will be working with specimens from both Earth and Life collections, as well as some material from the Library and Archives. The first stage will be making a detailed list of everything that needs to be moved, then I can go on to prepare the new store and get the supplies I’ll need to document, pack and transport everything safely.

Although most are specialist pollinators, about 10 per cent of bee species are parasites of other bees, taking advantage of the nectar and pollen collected by their host to feed their own young. These parasitic bees can be quite strange in appearance – not needing to collect pollen they have typically lost most of their hair and appear more like wasps.

Although most are specialist pollinators, about 10 per cent of bee species are parasites of other bees, taking advantage of the nectar and pollen collected by their host to feed their own young. These parasitic bees can be quite strange in appearance – not needing to collect pollen they have typically lost most of their hair and appear more like wasps.

The Crew is made up of eleven 14-19 year olds who are already passionate about natural history and we’re really pleased to have them on board. Many museums across the UK run youth forums to engage the young people within their community, who are often underrepresented in museum audiences.

The Crew is made up of eleven 14-19 year olds who are already passionate about natural history and we’re really pleased to have them on board. Many museums across the UK run youth forums to engage the young people within their community, who are often underrepresented in museum audiences.

![By Glen Fergus (Own work, Stewart Island, New Zealand) [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://morethanadodo.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/1024px-tokoeka.jpg?w=740&h=556)