A day in the life…

Ever wondered what we get up to all day? This video offers a nice flavour. Thanks to Tom Wilkinson and Tom Fuller in the University of Oxford Public Affairs Directorate for putting this together.

Ever wondered what we get up to all day? This video offers a nice flavour. Thanks to Tom Wilkinson and Tom Fuller in the University of Oxford Public Affairs Directorate for putting this together.

One of the most remarkable fossil sites in the world is located in Chengjiang in China, where exquisitely-preserved fossils record the early diversification of animal life. The 525 million year old mudstone deposits in the hills and lakes of Yunnan Province, South China are so fine that they have preserved not only the shells and carapaces of Cambrian animals, but also the detail of their soft tissue. In recognition, the site was added to the World Heritage list by UNESCO in 2012.

One of the most remarkable fossil sites in the world is located in Chengjiang in China, where exquisitely-preserved fossils record the early diversification of animal life. The 525 million year old mudstone deposits in the hills and lakes of Yunnan Province, South China are so fine that they have preserved not only the shells and carapaces of Cambrian animals, but also the detail of their soft tissue. In recognition, the site was added to the World Heritage list by UNESCO in 2012.

Professor Derek Siveter, a senior research fellow at the Museum, has been studying this material for a number of years, authoring a book – The fossils of Chengjiang, China: The flowering of early animal life – in 2004. But the rate of discovery of new fossils over the last decade has led to a wealth of new material to be documented.

So Derek recently headed back to the University of Yunnan for a two-week visit, where he began work on a revised edition of the book. Much of the documentation of these important fossils is currently in Chinese, so the new edition will bring the material to English-speaking researchers and fossils enthusiasts too. It introduces both the professional and the amateur palaeontologist – and all those fascinated by evolutionary biology – to the aesthetic and scientific quality of the Chengjiang fossils, many of which represent the origins of animal groups that have sustained global biodiversity to the present day.

Scott Billings – Public engagement officer

I’ve just received some fabulous pictures from a photo shoot here in the Museum. The building and its specimens are shown at their very best and the model’s striking looks add a sheen of glamour to each photo. But what makes these images really special is that the model is one of our own; Aisling Serrant is better known to Museum staff as a trainee education officer on the HLF Skills for the Future programme.

Aisling spent four months in the Public Engagement team in 2014, largely working with school groups and families. Not always the most glamorous job. In November 2014 we had the opportunity to see her in a completely new light. Oxford Fashion Week was coming to the Museum and they were running open casting sessions for models. Aisling remembers how she got involved:

**

When the initial meetings started taking place between the Fashion Week organisers and the Museum staff, my ears pricked up. Alongside studying or working I have modelled for years. My degree is in archaeology, so people have always found the combination with fashion modelling quite funny – perhaps imagining me standing knee-deep in a muddy trench in stilettos! It seemed too good to be true – could there really be a chance for me to bring my two contrasting types of work together?

I was delighted when I was asked to model in all three shows that were to be held at the Museum. They took place on Friday 7 and Thursday 8 November.

Friday night was a busy one with two shows in one night. I felt right at home, with the familiar faces of old friends like the T.rex and Iguanodon (oh and some of the staff members too!). However it did all feel a bit surreal.

The Museum Annexe had been transformed into the backstage area, but the last time I had spent so much time there I’d been running an archaeological dig activity with year 6 children in the Making Museums project. Now the place couldn’t have looked more different with rails upon rails of clothes, photographers’ flashes and the distinct smell of hairspray in the air.

Saturday night was the big finale to the week – the Birds of Paradise show in the Museum central court. The skeleton parade was parted so we could walk down the middle and the Triceratops skull was moved to become the backdrop for the first part of our walk. The museum was transformed into another world for the evening.

The addition of atmospheric music and such stunning outfits was truly breathtaking – enchanting at times, slightly eerie at others – but always fantastically dramatic. The nature-inspired outfits, some smothered in black feathers, others twinkling with jewel beetle shells, served as a reminder of how extraordinarily beautiful the natural world is.

**

Photographer Julia Cleaver was here for the shows and was so inspired by the venue and so enjoyed working with Aisling that she returned recently to do an extra photo shoot. These photos are the stunning outcome of that session. Many thanks to Julia for letting us share them here.

Rachel Parle, Interpretation and Education Officer

Fifty years ago this month the Royal Swedish Academy announced that Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin had won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. She remains the only British woman scientist ever to win a Nobel Prize.

The Museum celebrated Hodgkin’s achievement with a bust in the Court – the only female face among all the statues looking down on the dinosaurs. Although the bust is currently off display, undergoing conservation work, she deserves her place more than anyone: she first learned the skills of X-ray crystallography in the Museum, and carried out all of her Nobel Prizewinning work there.

Georgina Ferry, author of Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life, and a former author in residence at the Museum, reveals more about Dorothy’s work.

*

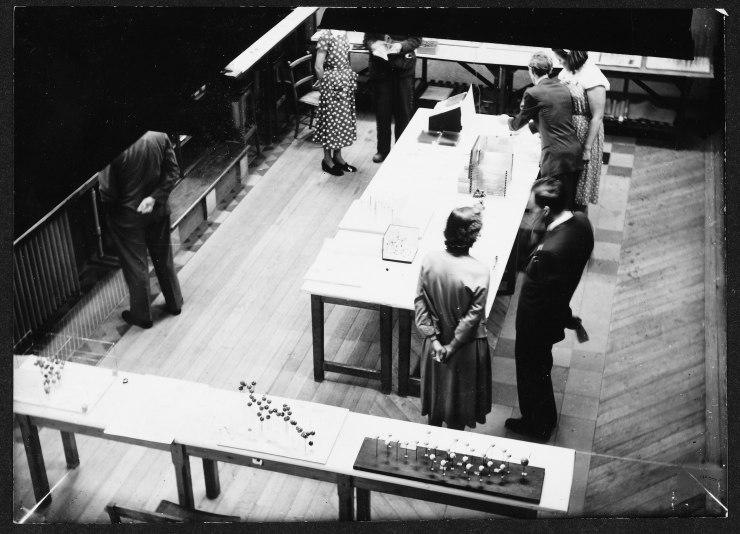

In 1928, when Dorothy Crowfoot (as she then was) arrived in Oxford to study chemistry, the Museum was still the centre of teaching and research in several science subjects including crystallography. The following year the department installed the equipment needed for X-ray work. Dorothy chose to do her Part II research project in X-ray crystallography, the first student to do so. From photographs of the patterns of spots generated by firing beams of X-rays through tiny crystals, she could calculate the positions of the atoms inside the crystal, and so understand how its structure influenced its chemical role.

At the time the whole Mineralogy and Crystallography Department worked and taught in the room under the tower where Samuel Wilberforce and Thomas Huxley conducted their famous debate on human evolution in 1860. There was a darkroom suspended from the ceiling for examining crystals, another curtained-off area for developing photographs, and the X-ray tube, connected to an alarmingly unsafe power supply, sat on a table in the corner.

After getting a first class degree in 1932, Dorothy went to Cambridge to do a PhD with JD Bernal. There she began to study biologically important substances such as cholesterol and pepsin.

After getting a first class degree in 1932, Dorothy went to Cambridge to do a PhD with JD Bernal. There she began to study biologically important substances such as cholesterol and pepsin.

Two years later she was back in Oxford with a fellowship at Somerville. She started her own research in a dingy semi-basement in the northwest corner of the Museum. That remained her lab for more than 20 years. It was there that she solved the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in crystals of penicillin and Vitamin B12, the achievements that won her the Nobel Prize.

All through this week, as the Nobel Prizes for 2014 are being announced, you can hear Dorothy’s life story told through her letters on BBC Radio 4, in the series An Eye for Pattern (it will be on iPlayer thereafter if you missed it).

With thanks to the Bodleian Library and the Department of Chemistry,University of Oxford for the use of the photographs.

Last Friday afternoon at around 5.30pm, just as I was about to go home after a busy week, the phone rang. It was BBC Radio Oxford asking if I would appear on the breakfast show at 7.50am the following Monday morning. They wanted me to talk about a new study published this week about the extinction of the dinosaurs…

The research, led by Dr Steve Brusatte from the University of Edinburgh, suggests that perhaps dinosaurs were rather unlucky not to have survived a meteorite impact 66 million years ago. The paper, which is published in Biological Reviews, suggests that a number of other factors were already weakening the dinosaurs’ survival chances, presenting a perfect storm of bad luck.

Commenting on this research on the BBC Oxford show, I explained to presenter Phil Gayle that the dinosaurs died out at the end of the Cretaceous period when an asteroid hit what is now the coast of Mexico (apart from the earliest birds, which had already evolved from dinosaurs and mostly survived).

But even before their extinction, the end of the Cretaceous was a time of great change. The climate became cooler than it ever had been during the 160 million years of dinosaur reign, and sea levels were changing quite dramatically, although this was not so out of the ordinary. More unusually, there was a massive amount of volcanic activity going on in India, forming one of the largest volcanic features on Earth – the Deccan Traps. This caused acid rain and cooling of the atmosphere in the short-term.

On top of this there was the enormous impact, thought to have been an asteroid around 6 miles in diameter. It left a crater over 100 miles wide and 10 miles deep near Chicxulub in Mexico. The impact would have caused massive earthquakes and tsunamis, acid rain, and a temporary removal of the ozone layer. A thick cloud of dust thrown up by the impact would have darkened the Earth and cooled the planet by several to a few tens of degrees.

![This shaded relief image of Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula show a subtle, but unmistakable, indication of the Chicxulub impact crater. Most scientists now agree that this impact was the cause of the Cretatious-Tertiary Extinction, the event 65 million years ago that marked the sudden extinction of the dinosaurs as well as the majority of life then on Earth. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech, modified by David Fuchs at en.wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://morethanadodo.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/256px-yucatan_chix_crater.jpg?w=740)

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech, modified by David Fuchs at en.wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The new study uses the most up to date information on the fossil record, and combines this with new and powerful statistical techniques to try and shed more light on these questions. The researchers found that the extinction of the dinosaurs was abrupt, coinciding almost exactly with the asteroid strike, although there was no evidence to suggest that dinosaurs around the world were already dying out before then, as some people have claimed.

However, they did find a decrease in the diversity of plant-eating dinosaurs in North America shortly before the impact; this might have disrupted the food chain and made the dinosaurs more susceptible to extinction. The decrease in diversity could have been caused by climate change, sea-level change or the volcanic activity, but without more data it’s still not possible to pin the reason down.

The findings led Dr Brusatte to suggest that if the asteroid hit at any other time in the dinosaurs’ history, they might well have survived. They were essentially just very unlucky, he claims. This is an interesting idea, but unfortunately there’s no way we can test it in a scientific way. A 6-mile wide asteroid hitting the Earth is an experiment you can only really run once, and it’s one I personally don’t want to see repeated!

It’s amazing that these incredible creatures, including the largest carnivore that ever lived on land, T. rex, could have become extinct in such a short space of time. They ruled the earth for nearly 160 million years and seemed invincible. The end of the Age of Reptiles seems somewhat poetic. And it makes me wonder, what might give rise to the end of the Age of Mammals?

Hilary Ketchum, Earth Collections manager

Earlier this year we had the pleasure of hosting the BBC iWonder team and evolutionary biologist and presenter Ben Garrod for a filming session all about the evolution of birds. BBC iWonder is a growing series of short but rich guides to subjects as wide-ranging as salt in your diet, the World Cup, and the holocaust, each designed to pique people’s interest and curiosity.

Ben’s guide is titled ‘Do Dinosaurs Still Live Among Us?’. This is a good question indeed and the answer is (sort of) ‘yes’. You can find out a lot more in the guide itself, which has just been launched here and features some lovely footage of the Museum and our cast of the famous Archaeopteryx fossil, the first found to show the traces of feathers on a dinosaur.

Needless to say we were very pleased when the iWonder team contacted us about their idea to look at the evolution of birds from dinosaurs using specimens in the Museum. The guide’s producer and director Ben Aviss explains how it came about:

We brainstorm ideas for new content for the guides and one of those was to look at dinosaurs, but what question might we ask? The idea of dinosaurs and birds sharing a common ancestry is something that not everyone may know about so we decided to look at that.

Ben Aviss had already seen the Museum on Ben Garrod’s BBC4 series Secrets of Bones and thought it looked great. “The more we chatted about the things we might want access to, the more we realised you offered everything we needed,” he adds.

It was a third return to the Museum for Ben Garrod who, as well as filming sequences for Secrets of Bones, had also run our Capybara Construction special event earlier in the year. He explains the appeal of returning for the iWonder guide:

This iWonder guide represents a new and fun way to retell a key moment in evolutionary history – the transition from dinosaurs into modern birds and I’m pleased with the final result. It’s informative and interesting but more than that, it looks good and that is in no small part down to the setting in which we filmed.

I keep coming back again and again because I genuinely love the Museum. The collection is laid out in a way that gives the visitor lots of time and space to explore and the specimens themselves are great – I’m still finding new things every time I visit.

There are plans for further iWonder guides that go richer and deeper, with greater interactivity and content. Let’s hope the collections – and Ben’s enthusiasm – brings the team back to tell another story here soon.

Scott Billings – Communications officer