A tale of two seahorses

Real or fake? Do replicas have a value of their own? Elaine Charwat is exploring this in her PhD, using the Museum’s large collection of natural history models and casts to research their role in science. Here she tells the story of the fascinating fish that caught her imagination…

By Elaine Charwat

It all started with a seahorse. Last year, I walked into a little seaside shop, and I spotted a seahorse. I instantly flipped back to the happy day I bought my first dried seahorse as a child, the beginning of a life-long passion for the natural world. The man behind the counter smiled: “It’s a fake.” Really? “3D printed.” It looked absolutely perfect. Tracing its lines with my fingers, I said, “It’s a model”.

Ever since I became interested in models and replications, I have encountered this perception of them as “fakes”. Quite recently, I heard the curator of a natural history museum call the cast of a dinosaur skeleton a “fake”. Models in natural history – and in this I include casts and reproductions – are what the Germans call “Wissensdinge”, objects that contain, distribute and generate knowledge. In this aspect, the real specimen and the model meet. Models are made from a vast array of materials with often astonishing skill and technologies. They represent what we know about a particular organism at a certain point in time. They have a history, a context.

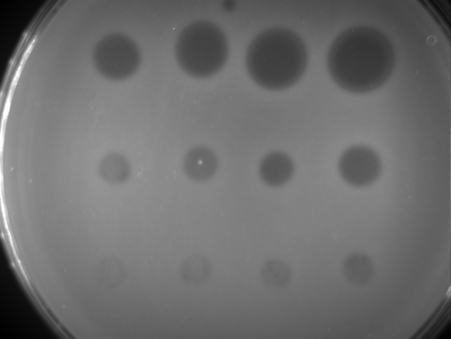

But they are also ambassadors, and this is something I realised when I held the “fake” 3D-printed seahorse in my hand. While it becomes ethically problematic to buy specimens of organisms like seahorses, something of it is captured, and communicated, in a reproduction. I can still trace its exoskeleton, and marvel at its strange symmetry. This symmetry, incidentally, is being analysed for its potential in robotics. Seahorses have unusual tails – instead of the cylindrical trail structure found in most animals, theirs have a square cross-sectional architecture, resulting in a unique combination of toughness and flexibility. In fact, when studying the unique abilities of the seahorse’s tail, researchers have actually used 3D-printed specimens.

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History has a largely unexplored wealth of models and casts. Many of them date to the second half of the 19th Century, the heyday of their production. Made from glass, wax, metal, wood, plaster, papier-mâché or, indeed, actual bone and feathers, they were modelled, cast, sculpted, glued, painted and mounted to enhance and preserve our understanding and appreciation of nature. But they also tell of scientific discoveries and controversies, research and teaching, rivalries and collaboration, politics and society, ideas and identities.

I will trace these complex relationships in a collaborative and interdisciplinary PhD project called “Nature of Replication”. This is funded by the AHRC and jointly supervised by the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, and the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

The 3D-printed seahorse now lives alongside my real seahorse. So I like to think of my project as a journey that started with one seahorse, and continues with another.