Re-collections: William John Burchell

By Matt Barton, Digital Archivist

Over the last few months, I have been working on cataloguing and rehousing the archival collection of William John Burchell (1781-1863). Burchell was an important early naturalist, explorer, ethnographer, and linguist who worked in South Africa and Brazil, contributing greatly to our understanding of the flora and fauna of these areas. He was also a highly talented artist!

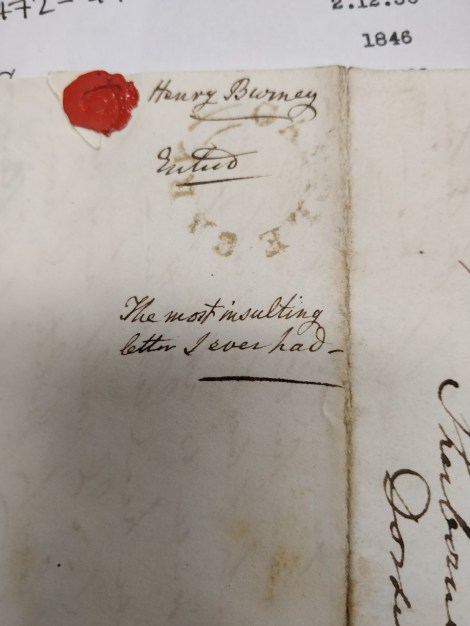

Burchell amassed huge natural history collections and described many new species, but his work was not widely recognised in his lifetime. Although he received an honorary degree from Oxford in 1834, he felt neglected by the government and scientific community in Britain. Later on in his life, Burchell became something of a disillusioned and reclusive figure, strictly guarding access to his collections and publishing few of his own findings.

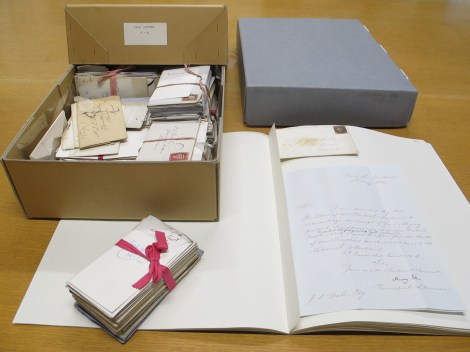

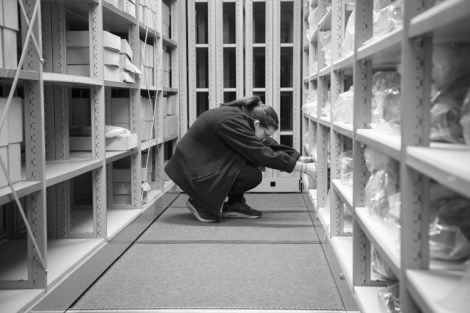

The first section of the Burchell collection that I tackled was his correspondence. I am happy to report that our wonderful volunteers – Lucian Ohanian, Mariateresa DeGiovanni, Naide Gedikli-Gorali and Robert Gue – have now finished digitising this material and we have made the scans available to all on Collections Online. Now that the digitisation of the Burchell correspondence is complete, we are able to more easily search his letters, and learn more about his motivations to conduct expeditions so far afield.

Burchell first left the British Isles in 1805 when he travelled to the island of Saint Helena. He moved to Cape Town in 1810 before beginning his expedition into the interior of South Africa in 1811. This epic journey covered 7000 kilometres, mainly through terrain unexplored by Europeans at the time. It lasted four years, with Burchell only returning to Britain in 1815.

What prompted him to undertake such an extraordinary expedition? In a letter home to his mother written on 29th May 1811, Burchell relates several potential motivations. Firstly, he describes his frustration with the East India Company (his employers in St Helena), and his desire for a new beginning: “I have been patient with the Company’s promises till it is become evident to everyone that I was only wasting my life living any longer in St Helena.” He goes on to stress his enthusiasm for scientific research, which may also have been a motivating factor behind his journey: “I have thought it best to give free indulgence to my inclination for research which I feel so natural to me, that I flatter myself it will be my best employment.” Finally, Burchell shows a more pecuniary motive when he notes, “I do not consider myself out of the way of making money, when I think of the value of what I shall be able to obtain in my journey.”

Burchell closes the letter very affectionately, suggesting he had a close relationship with his family. More than half of the letters in our collection written by Burchell are addressed to his parents or sisters. He ultimately left his specimens to his sister, Anna, who in 1865 donated his botanical specimens to Kew Gardens and his other specimens to Oxford University Museum of Natural History, with the archival collection following later.

No longer an underappreciated figure, Burchell is recognised as a pioneering and significant naturalist. Through preserving and reading our Burchell archive, we can continue to shed more light on his life and personality.

If you would like more information on this fascinating individual, we have a short article about Burchell on our website.