Tongue-testing fossils, Victorian-style

by Anna Dewar, Museum intern

Victorian geologist William Buckland had an impressive knack for finding fossils. He named the first dinosaur, Megalosaurus bucklandii, in 1824 after its discovery in Stonesfield near Oxford. You can see the Megalosaurus fossils on display in the Museum today.

Working as an intern here over the last few weeks, I have been confronted with hundreds of Buckland’s specimens, many of which have never been catalogued.

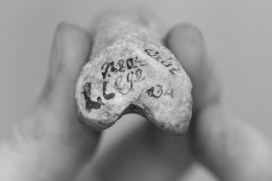

A couple of weeks ago I stumbled upon a cave bear toe bone, or phalanx, with a very unusual label. Written in Buckland’s handwriting was ‘Cave Bear Liège’ and the number ‘234’. No other fossils in this collection were numbered, and after a database search not one other specimen had been found near this Belgian city.

I then discovered something that, while it could be coincidence, demanded further investigation. On page 234 of Lyell’s Principles of Geology, Vol. II, published in 1832, appears the only mention of Liège in the entire book:

In several caverns…near Liège, Dr. Schmerling has found human bones in the same mud…with those of the…bear, and other… extinct species.

The mysterious ‘234’ perhaps references this page number; if so, it would indicate that the specimen was one of those Philippe-Charles Schmerling had discovered. But if this is the case, how did this fossil end up in Buckland’s possession?

After some further research, I learned that Schmerling presented his Liège findings to a group of naturalists including Buckland in 1835. Schmerling argued that the human bones he had discovered were also fossils, and so the same age as the bones of extinct animals.

Buckland countered Schmerling’s claim by saying that “these animals lived and died before the creation of man” and that, instead, the human remains found alongside extinct species could be explained by burial. French geologist Élie de Beaumont, who was present at the meeting, remembered how Buckland chose to voice this opinion:

Mr Buckland took a bear bone, and put it on the tip of his tongue, to which it remained suspended…and, turning to…the assembly, Mr Buckland repeated many times…: ‘You say that it does not stick to the tongue!’ Mr Schmerling tried a few times to stick to his own tongue several human bones, but he did not succeed.

An entirely speculative artist’s impression of William Buckland’s ‘tongue test’ demonstration

Whilst speaking to a crowd with a fossil on your tongue seems odd, Buckland did have reason. It was difficult to estimate the age of a specimen, and this ‘tongue test’ supposedly related to the mineralisation of the bone: if it stuck to your tongue, it was a fossil; if it didn’t stick, it was bone.

While Schmerling was left humiliated, it was realised after his death that he had found human fossils after all, including those of a Neanderthal. Obviously the tongue test was not as foolproof as Buckland believed.

While we’ll never know for sure, Buckland, by writing ‘234’, may have linked this bone from Liège to Schmerling. It also happens to be a bear bone, small enough that it could conceivably adhere to a tongue. Could Buckland have slipped it into his pocket after his demonstration? Or perhaps for Schmerling, the bone, after having been coated in Buckland’s saliva while he himself stood humiliated, may have somewhat lost its appeal.

Whether or not this bone is THE bone at the heart of this spectacle, it does seem that life as a palaeontologist in the 19th century certainly wasn’t boring.

For Monica in Minerology, I wanted to know more about what people historically considered ‘sympathies’ of gemstones. She directed me to Nichols’ Faithfull Lapidary of 1652, the oldest book in English about the properties of gemstones. The Museum has a copy of the book on loan to the Bodleian, so I’m heading in the direction of that most famous library to get to see the book, perhaps on my next visit.

For Monica in Minerology, I wanted to know more about what people historically considered ‘sympathies’ of gemstones. She directed me to Nichols’ Faithfull Lapidary of 1652, the oldest book in English about the properties of gemstones. The Museum has a copy of the book on loan to the Bodleian, so I’m heading in the direction of that most famous library to get to see the book, perhaps on my next visit.