First Impressions: exploring early life through printmaking

by Rachel Parle, public enagement manager

In each of our special exhibitions, we complement contemporary scientific research with contemporary art. In recent years this has included Elin Thomas’s crocheted petri dishes, Ian Kirkpatrick’s migration and genetics-themed installation, and who could forget the enormous E. coli sculpture by Luke Jerram?!

For our current exhibition, First Animals, we’ve taken this collaboration to a new level by commissioning original works from a total of 22 artists, all part of Oxford Printmakers Co-operative (OPC) – a group of over a hundred printmakers which has been running for more than 40 years.

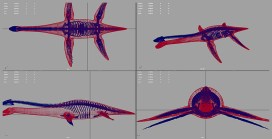

First Animals looks at the very earliest evidence of life on Earth, dating back half a billion years. Some of the fossils on display are shallow impressions in the rock – the only direct evidence we have that life existed at that time.

To kick-start the project we ran a series of workshops for OPC artists to meet the Museum researchers working on the exhibition, and to see the fossils first hand. There were also opportunities to draw directly from these unique fossils, many of which have never been displayed in the UK before.

Discussions between researchers and artists revealed fascinating similarities between these ancient fossils and the process of printmaking. Sally Levell, of Oxford Printmakers Co-operative, explains:

I was completely fascinated by the fossil collection in the Museum, especially the fine specimens from Chengjiang and Newfoundland. They are preserved as mere impressions in the rock, so they are, in essence, nature’s prints.

Each printmaker partnered with a researcher who could answer questions, provide extra info and help the artist decide which specimen or subject to depict in their final print. It’s clear from talking to the printmakers that this direct contact with the experts was invaluable and made the work really meaningful.

We couldn’t have worked without the patient explanations and “show and tell” sessions with the three main researchers – Dr Jack Matthews, Dr Imran Rahman and Dr Duncan Murdock. They were just excellent and their dedication to their work was an inspiration to all of us printmakers.

Sally Levell

Over a period of around seven months, ideas blossomed and printing presses were put into action, with the printmakers exploring the forms, textures and evolution of the fascinating first animals. The final result is First Impressions, an enticing art trail of twenty-five prints dotted around the Museum, both within the First Animals exhibition gallery and nestled within the permanent displays.

Such a large group of artists brings a huge variety of techniques and styles, all under the umbrella of printmaking; from a bright, bold screen print in the style of Andy Warhol, to a delicate collagraph created from decayed cabbage leaves! To take part in the art trail yourself, simply grab a trail map when you’re next in the Museum.

But our foray into fossils and printmaking didn’t stop there. OPC member Rahima Kenner ran a one-day workshop at the Museum where participants made their own intaglio prints inspired by the First Animals fossils. The group of eight people featured artists and scientists alike, all keen to capture the unique fossils through print techniques.

Designs were scratched onto acrylic plates and inked up, before a professional printing press created striking pieces to take home. Participants also explored techniques such as Chine-Collé, the addition of small pieces of paper to create texture and colour underneath the print.

It was a delight to be able to share with the group our enthusiasm for these discoveries in the medium of making the drypoint prints and to share their enjoyment of learning and using the new techniques. Some lovely work was produced in a single day.

Rahima Kenner

The First Impressions project has been transformative for the Museum team and for the Oxford Printmakers Co-operative. Catriona Brodribb describes its impact on the printmakers :

It’s been a great opportunity to challenge one’s own artistic boundaries in terms of stretching the imagination, and for our members to throw themselves into something new, and enjoy responding to such ancient material in a contemporary way.

The First Animals and First Impressions exhibitions are open until 24 February 2020 and are free to visit.