More than mimicry

A small exhibition has popped up on the upper gallery of the Museum, showcasing natural historian Henry Walter Bates. He’s famous for his theory on mimicry, but, as exhibition curator Gina Allnatt explains, there’s a lot more to discover about Bates.

**

Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace are now widely recognised as the co-discoverers of the theory of evolution. They are both established figures in the natural history world, but it was a lesser known contemporary who gave them a missing piece of the puzzle.

Henry Walter Bates was born in Leicester on 8th February 1825. He was originally apprenticed to a hosiery manufacturer, but his passion for insects sent him on a completely different path in life. In 1844, Bates encountered Wallace in a library, and the two men found they shared a mutual love of nature. Bates introduced Wallace to the field of entomology (the study of insects) and it wasn’t long before the two were planning a joint expedition to the Amazon. They funded the expedition almost entirely through the sale of specimens they collected. Wallace returned to England after four years, but Bates remained in the Amazon for a further seven years. When he finally returned to England he had amassed a collection of over 14,000 insects. 8,000 of these were new to science.

Bates is most famous for the work which bears his name: Batesian mimicry. Batesian mimicry is when a harmless species mimics the warning colours or behaviour of a harmful species.

The mimic then benefits from the protection of the model. For example, the Hornet Moth (Sesia apiformis) is completely harmless, but looks like a wasp and benefits from the protection of the wasp’s warning colours. The moth is the mimic and the wasp is the model.

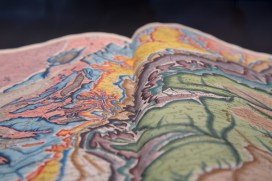

This Museum’s historical butterfly collection contains over 200 specimens collected by Bates, and thousands of other insects collected by him in the overall Entomology collections.

The specimens came to the collections via different routes. Some were purchased directly from Bates by Professor J.O. Westwood, the Museum’s first Hope Professor of Zoology. Bates material also arrived through acquired collections, such as those purchased from natural history specimen dealer Samuel Stevens. Other specimens of interest in the Lepidoptera collections purchased from Bates include an unusual net cocoon from a rare moth in the family Urodidae. The Urodidae are an unusual form of moth that build cocoons resembled a mesh bag with an opening at the bottom. One theory for this unusual structure is to allow rainwater to flush through it easily, without drowning the pupa inside. In the Amazon rainforest, which is prone to heavy rainfall and flooding, this is a huge advantage.

The exhibition, which can be seen until 26th February 2016, will reveal much more about Bates and his contribution to modern-day science.

Gina Allnatt, Curatorial assistant (Lepidoptera)